Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

Last year, China turned the nickel market on its head after the world’s biggest stainless-steel producer, Tsingshan Holding Group, agreed to supply about 100,000 tonnes of matte (containing approximately 65-75% Ni) to Huayou Cobalt and battery materials maker CNGR Advanced Material.

The market response was not pretty.

The news signalled that the mainly Chinese-funded nickel pig iron (NPI) producers in Indonesia were now looking at making nickel matte – a well-known process – which would provide additional units available for nickel sulfate production to be used in the battery production network.

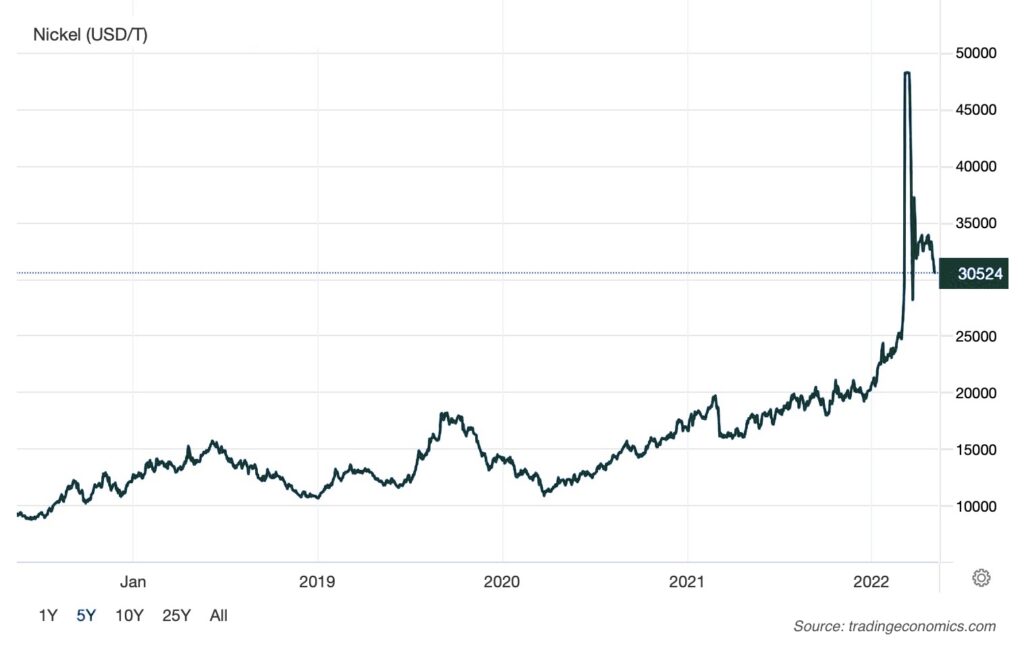

London’s nickel prices fell nearly 9% the next day and in Shanghai dropped the most in nine months. The three-month nickel contract on the London Metal Exchange dropped as much as 8.5% to US$15,945 per tonne, its most significant intraday loss since December 2016, and overall, LME prices were down about 20% a few weeks later.

The response was grim because a lot of people recalled all too clearly what happened to stainless steel when China flooded the market with NPI. The markets worried the same thing was going to happen and that ultimately prices would plummet because of all the excess supply.

What actually occurred in 2021 was a rise in demand for battery grade nickel that outperformed expectations. Somewhere between 300,000 and 400,000 tons of nickel went into battery precursors in 2021, some 100,000 tons higher than forecast. On top of that, stainless steel demand increased by something like 9%, which was another unexpected area of growth.

So, the nickel market went into a deficit situation to the tune of almost 200,000 tons in 2021, which was absorbed by LME inventories. In other words, the elasticity was taken up by the LME inventory which kept prices appreciating but without enabling them to really take off.

In late 2021, some expected developments occurred: firstly, Tsingshan claimed that they had shipped the first of their matte product to battery producers. Secondly, two HPAL operations in Indonesia (out of a multitude that were announced by the Chinese), began the commissioning process and one of them, Lygend, shipped something like 11,000 tons of MHP, which is roughly 40% nickel.

This did not have the effect on nickel price that people had expected. By the end of 2021, nickel prices had breached $20,000 a tonne and by March, 2022, prices went wild and rose to very nearly $50,000/t. There was an expected pullback from those historic highs but here we are in May, 2022, and we are still seeing prices over $32,000/t – far in excess of most investors’ expectations in early 2021.

Over the longer term, our forecast is that, even if the Ukraine conflict ends sooner than expected, and that there is a relatively swift return to peace, the demand for battery grade nickel is going to keep the nickel price at elevated levels.

Anthony Milewski — The Oregon Group

What is fuelling these prices? Obviously, the Ukraine war has put a lot of question marks into global commodity supply, as well as driving a surge in oil. Oil is energy. Energy is a big input into nickel production. Whether it’s ferro nickel or Class 1 nickel, it doesn’t matter. Energy is a major component. And we’ve also seen battery uptake of nickel has not slowed down. There’s huge demand. The LME inventory for nickel is around 80,000 tons now, of which maybe 60,000 tonnes is in nickel briquettes, available to be dissolved into nickel sulfate.

Our understanding is all of the material is actually spoken for. So, if you wanted to buy nickel briquettes off the LME, it is almost impossible. So nickel production is being impacted.

The other thing that people are realizing is that, although a company like Tsingshan said “hey, we can make a lot of nickel matte,” it’s becoming well-known that matte is not a direct substitute for MHP or nickel sulfate.

You see, making nickel sulfates from MHP and nickel briquettes is relatively straightforward. You can dissolve both materials in acid at atmospheric temperature pressure around 80 degrees Celsius and then you eliminate the impurities, whether they be iron or zinc and chrome, magnesium, manganese, through various steps, mostly solvent extraction. And you precipitate out a pure nickel sulfate.

In comparison, nickel matte contains unoxidized sulfur. And, in order to oxidize that sulfur, you need pressure and you need an oxidant such as oxygen, which means you need autoclaves. One nickel sulfate producer in China actually went on record and said they can’t take matte until they invest about USD $30 million and spend at least one year on upgrading their facilities. So, for matte to have an impact on nickel sulfate production, we’re talking about a year to 18 months of investment and infrastructure changes in China.

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

Another big factor pushing the nickel price up is that Indonesia has reaffirmed their stance and commitment on the moratorium on shipping unprocessed ore to China. They want that ore to be upgraded in Indonesia so that more of the profit stays in-country. In fact, they’re even talking about making sure the ore is upgraded to a certain class of product or intermediate before it gets exported.

That’s caused a lot of concern regarding a shortage of ore being shipped to China to make NPI, which is used in the stainless industry. Again, this is on the back of the unexpected growth in stainless production.

The stainless market is expected to ease off a little bit this year with China now focusing on making 200 series and 400 series stainless, which are very low nickel or no nickel. This is something that happened in 2005 to 2008 when nickel prices were around $50,000 a tonne. That move is expected to ease some of the pressure off demand.

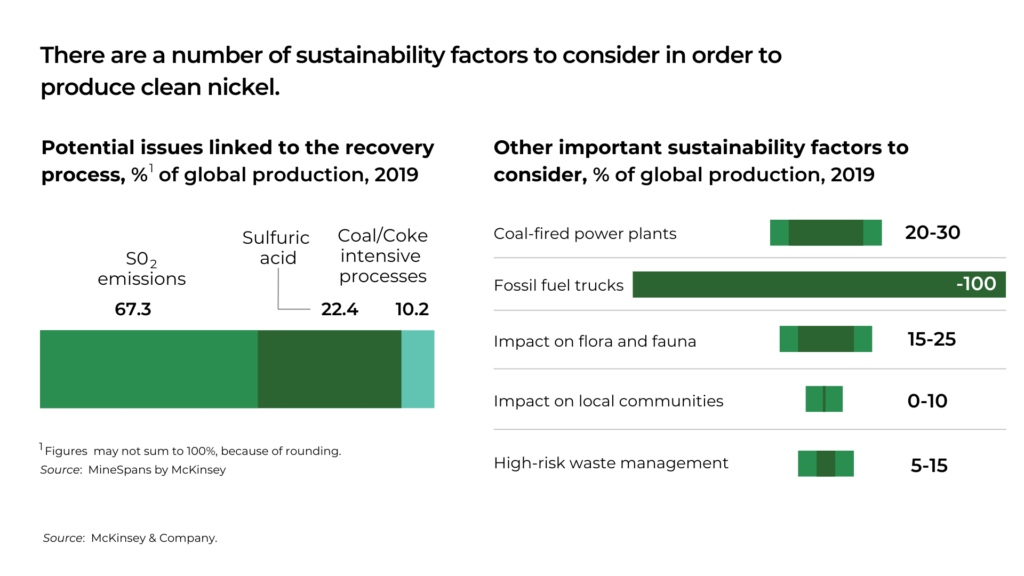

However, we have another factor: many companies are now really aware of the ESG credentials of the nickel that they’re procuring. This awareness is impacting a lot of the nickel operations in Indonesia because the ESG metrics for some of these countries is not at a level that is passable in Europe or North America. At the moment, it’s viable in the court of public opinion to purchase nickel from these operations, but it’s unclear how long it will remain so, and thus they do not want to take any risk.

So, more and more manufacturers are pursuing nickel units that are, shall we say, lily white in terms of ESG credentials. The trouble with that approach is such units are few and far between.

Then there are the supply chain issues caused by Covid and sanctions which are affecting shipments of materials. And, on top of everything else, a lot of companies, OEMs, are looking to set up integrated supply chains in their own jurisdictions because they’ve worked out that the world has entered what looks to be a long period of de-globalization.

If you’ve not listened to it yet, head over to the TOG podcast introducing deglobalization. I won’t go into it in detail here, other than to say that certain battery companies want their nickel from North America because they don’t want to be at the whim of Chinese production. The same goes for nickel producers in locations where the shipping lines that move their material are having to avoid Russia.

The speed and depth of these changes will depend on how long the conflict in the Ukraine lasts and, by that I mean, how long the sanctions against Russian companies last. Factoring in what we know at this time, we believe there’s going to be a slight increase in available nickel units from Indonesia, specifically designed for the battery market, during 2022. However, we also believe the demand for batteries will outstrip that increase in supply in the short term.

Over the longer term, our forecast is that, even if the Ukraine conflict ends sooner than expected, and that there is a relatively swift return to peace, the demand for battery grade nickel is going to keep the nickel price at elevated levels. We may see a pullback, but it would not be unreasonable to expect prices to remain well north of $20,000 a tonne, maybe up to $25,000 a tonne.

Consequently, higher prices over the long term will enable nickel producers such as Sherritt, which has announced expansion, and other producers to reinvest, to generate some free cash flow and invest in their operations, to ramp up production.

It should also allow for other projects to raise financing, raise the money to be put new projects into production, including some big, undeveloped deposits in North America.

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.