The approval rate for rare earth export licences from China has climbed from 25% to 60%, according to European supplier group CLEPA. But shipments destined for the US or routed through third countries like India remain deprioritised, sustaining risks to supply chains despite the easing of earlier panic.

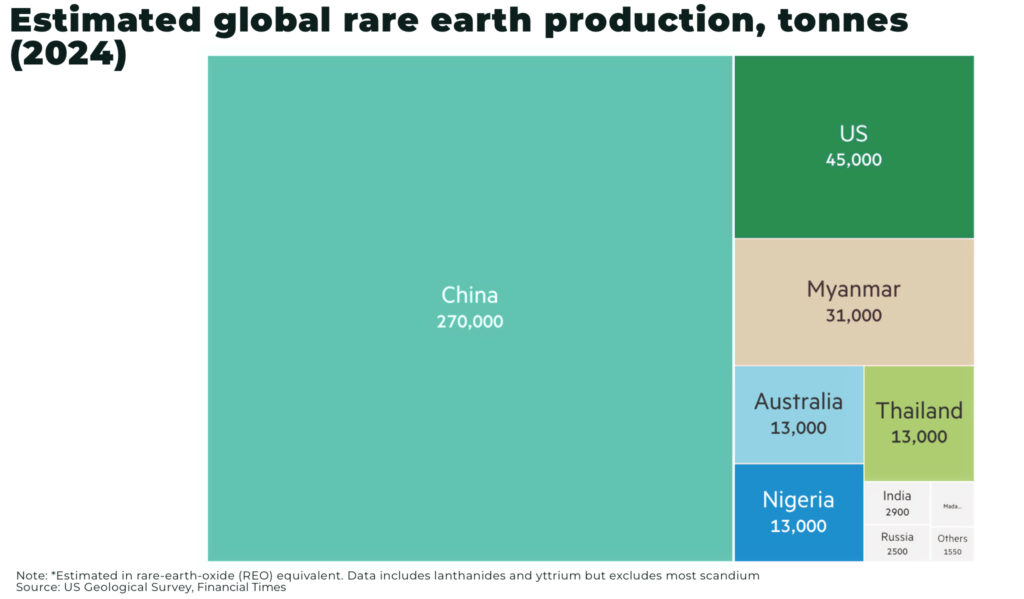

China, which accounts for over 90% of global rare earth magnet production, introduced tighter export controls in April 2025, requiring licences for seven rare earths and related magnets. The move was a direct response to US tariffs and broader tech export restrictions.

Since then, exports of Chinese rare earth magnets have dropped by roughly 75%, triggering supply shortfalls for automakers and defence suppliers. Ford CEO Jim Farley confirmed that factories had been shut down in recent weeks due to magnet shortages.

China’s commerce ministry and customs officials have reportedly started to demand additional inspections and third-party chemical testing and analysis of products that are not included in the original control list, according to Chinese companies and western industry executives.

“As long as it contains even a single sensitive word [such as magnet], customs won’t release it — it will trigger an inspection, and once that starts, it can take one or two months,” a salesperson at a Chinese magnet exporter told the Financial Times.

Despite a rare earth truce between the US and China signed in London earlier this month, intended to “expedite” approvals, implementation remains unresolved, according to Reuters. The Chinese commerce ministry and customs authorities are reportedly holding up not just controlled items, but unrelated shipments like titanium rods and zirconium tubes due to keyword flags like “magnet.”

One US supplier, Dexter Magnetic Technologies, has received just 5 of 180 licences submitted since April — none for defence-related applications.

“It’s an extended delay,” CEO Joe Stupfel told Reuters. “It’s 45 days trying to get the paperwork right for the supplier, and then it’s 45 more days or so before any licences are granted.”

To avoid port bottlenecks, some exporters are switching to air freight, accepting higher costs in exchange for a lower chance of delays. While this workaround helps move smaller cargoes, it’s not viable at scale.

Industry leaders warn the current stopgap approvals aren’t enough to stabilise supply chains long term. “We’ve avoided collapse for now,” one European auto supplier told Reuters, “but the system is still fragile.”