Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

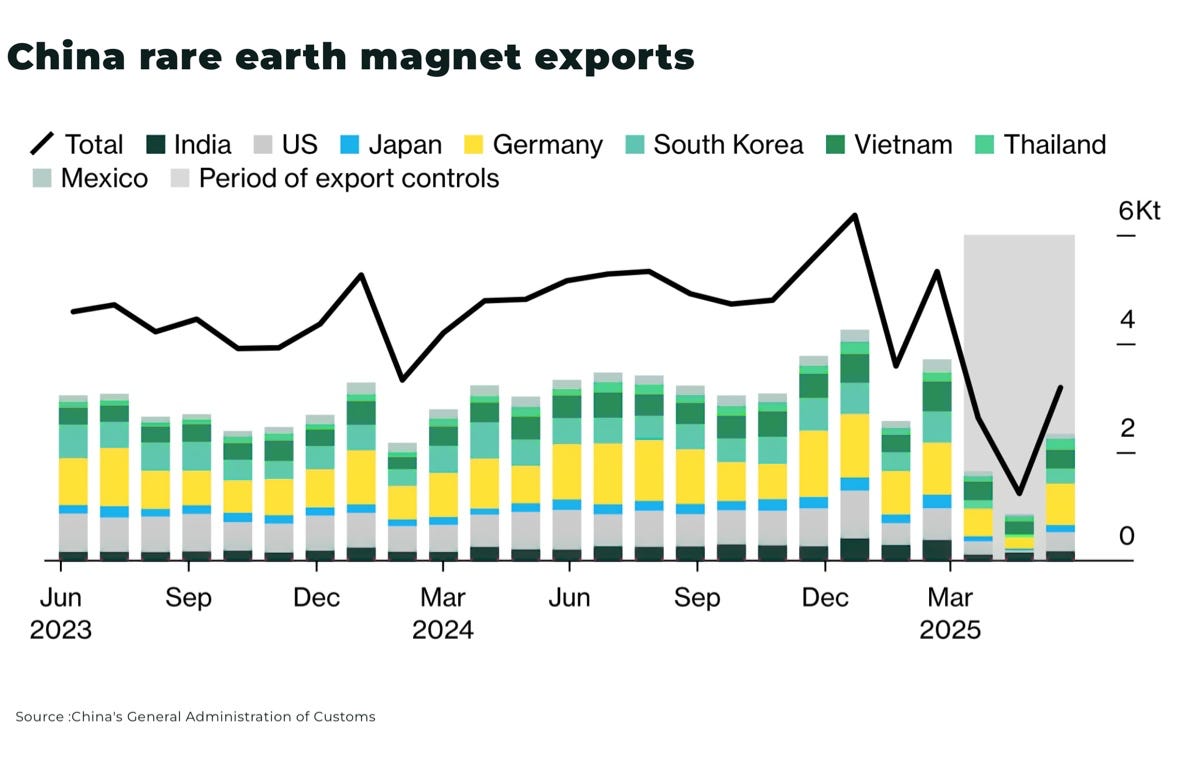

In May 2025, US rare earth magnet imports from China collapsed 93.3% after Beijing tightened export controls, escalating its use of critical minerals as leverage in the deepening trade war.

The move threatened entire multi-trillion-dollar industries across the West — including defense, tech, electric vehicle, clean energy, aviation and medical sectors which depend on Chinese supply chains for rare earth magnets, with no viable short-term substitutes.

Yes, there are stockpiles, but they quickly began to run low, triggering alarm across the West.

The “light is turning from yellow to red” a senior defense industry source told The Telegraph, concerning American companies’ ability to source rare earths.

“I can tell you…we talk about this daily and our companies talk about it daily,” Dak Hardwick, the vice-president of international affairs at the Aerospace Industries Association trade group, told the Wall Street Journal.

“The whole car industry is in full panic,” said Frank Eckard, CEO of Magnosphere, a German magnet maker, to Reuters in June. “They are willing to pay any price.”

“Fighter jets, drones, and radar systems rely heavily on rare earths, not only for avionics but also for stealth coatings, electronic warfare, and propulsion systems. If the current restrictions escalate into a full embargo, national security could be compromised” — John Persinos, editor-in-chief of Aircraft Value News

One US drone supplier to the military reported delays of up to two months, prices for materials in the defense sector have increased x5, and in one case, at least x60 — the list goes on.

As we, and others, have warned for years: America’s critical mineral strategy threatened disaster. Now, the US is in a disadvantaged position as it urgently engages in talks with China to resolve the issues over rare earth restrictions — yet China still deprioritises the US defense sector in exports.

However, it appears the West has finally realized the scale of the threat and prioritized a series of policy measures to address the crisis — from investment to geopolitics — but can they work in time?

Why rare earths are strategically critical

Rare earth elements — 17 metals, including neodymium, praseodymium, terbium, and dysprosium — are essential in manufacturing permanent magnets essential to, for example, EV motors, cancer diagnosis, wind turbines, guided missile systems, and the F-35 fighter jet.

China’s rare earth monopoly and strategic Leverage

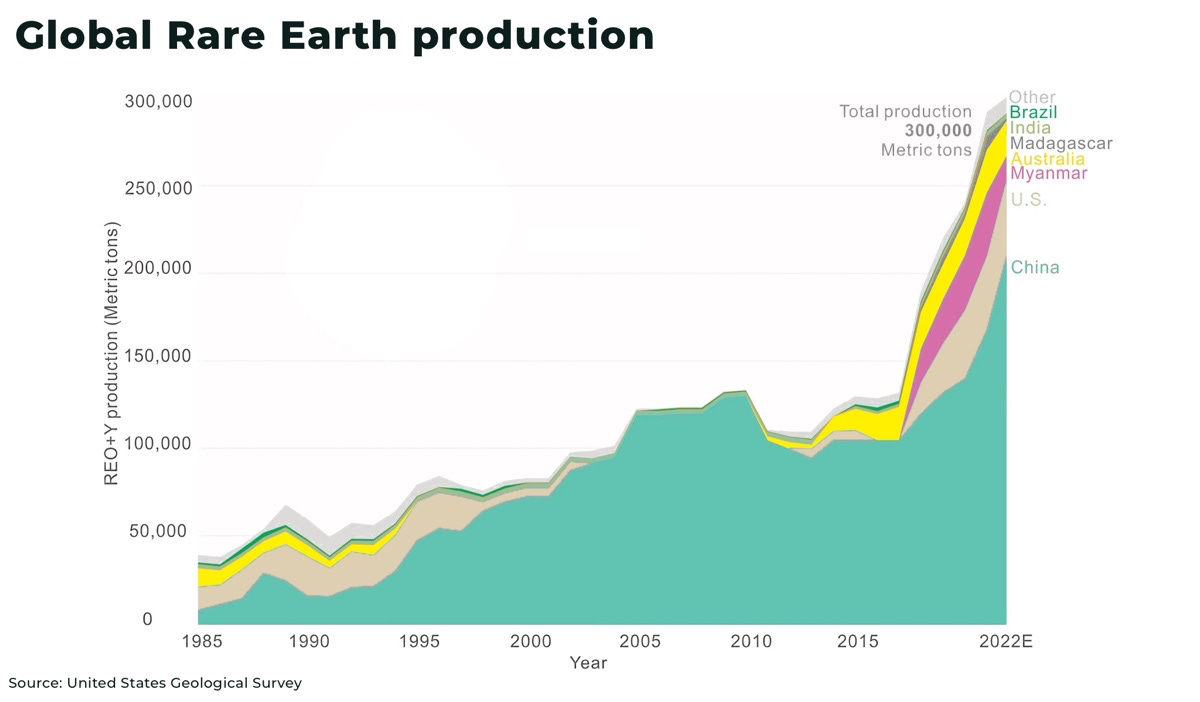

Despite being geologically widespread, rare earths are difficult and expensive (both financially and environmentally) to mine and process — allowing China to invest and build out global capacity representing:

- mining at 70%

- and processing at 90%

Today, especially in the renewed trade wars, this gives China significant geopolitical leverage.

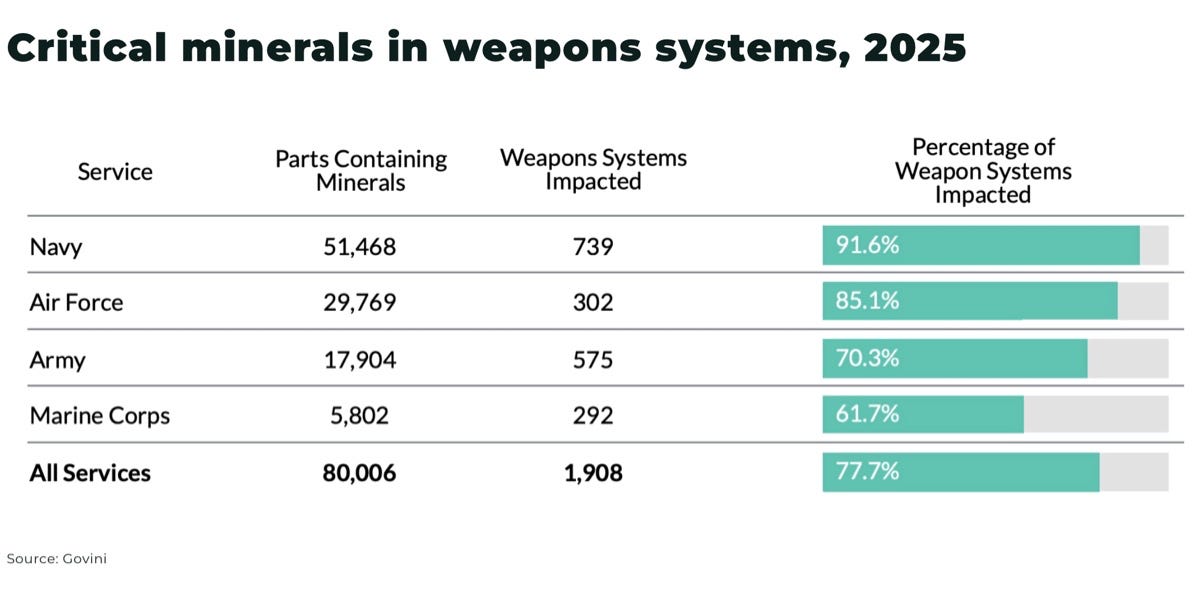

For example, the US Department of Defense relies on Chinese supply chains for components used in 1,900 weapon systems, encompassing over 80,000 individual parts — threatening 78% of US military weapon systems, according to a recent report from Govini.

The West can no longer treat rare earths as just tradable commodities; they are national security assets.

Government intervention: United States

It will be one of the great questions: how the US national security apparatus allowed China to monopolize it’s hold on key critical minerals such as rare earths, despite successive serious warnings, even after the disruption of Covid to supply chains.

However, the US Department of Defense now appears to be fully engaged.

In July 2025, the Department of Defense (DoD) took a US$400 million equity stake in MP Materials, America’s only active rare earth mine at Mountain Pass, California. The DOD also provided a $150 million low-interest loan and introduced a $110/kg price floor for neodymium-praseodymium oxide (NdPr). That pricing floor creates revenue stability to de-risk private investment in refining and magnet production.

Apple followed with a US$500 million investment with MP Materials to secure domestic supply chains for rare earth magnets in iPhones and Macs. Apple is co-developing recycling tech and new US-based processing facilities. Corporate demand, aligned with government funding, forms the cornerstone of new U.S. industrial strategy.

According to a recent Reuters report, this investment by the DoD is “not a one off”, with similar deals expected as part of a multibillion-dollar investment by the Pentagon to strengthen U.S. production of essential minerals and challenge China’s dominance in the sector.

Australia: a parallel playbook

Australia — which is the fourth largest rare earth producer with 5.14% of global products — is also reportedly considering its own price floor scheme for critical mineral miners, especially rare earts. It has committed A$1.2 billion to a strategic critical minerals reserve and is backing Lynas Rare Earths (which opened Australia’s first rare earth processing plant), Iluka Resources, and Arafura Rare Earths (which last year received A$840 million in funding to create the country’s first combined mine and refinery for rare earths).

Europe: lagging behind

Europe has launched the Critical Raw Materials Act to mine 10%, process 40%, and recycle 25% of its critical mineral needs by 2030. Nearly 50 projects have been approved across Spain, France, Sweden, and Belgium.

However, as we warned in our article Germany struggles to avoid another geopolitical disaster, this time over critical minerals, Europe has no operational rare earth mines and only two processing plants — one in Estonia and one in western France, which is only plant outside of China that can process all 17 different rare earths.

Geopolitical expansion: Myanmar (and Ukraine and Greenland)

The next stage in rare earth realpolitik is geopolitics – with the West starting to leverage influence to shift other major producers away from China.

Myanmar is the most important rare earth actor outside of China, with China importing up to 60% of its heavy rare earths from Myanmar, particularly from Kachin State — where insurgents and violent conflict disrupt supply and price volatility.

The Trump administration has reportedly heard “competing proposals that would significantly alter longstanding US policy toward Myanmar, with the aim of diverting its vast supplies of rare earth minerals away from strategic rival China.”

Then, in July 2025, the US Treasury Department’s lifted sanctions on some allies of Myanmar’s military junta.

There are huge challenges to reorienting rare earth supply chains in Myanmar from China, but it’s a sign of the importance put on rare earths that the US would even consider threatening China in what it would consider it’s own backyard.

Another country with a new deal with the US for rare earth deals is Ukraine. We do not believe, with the ongoing conflict, there will be any mine development anytime soon (especially with much of the now reserves in Russian-held territory). However, we do believe it is worthy of note that President Trump has highlighted the importance of the minerals as priority in the deal.

And then there’s Greenland. US President Trump has repeatedly signalled his desire to annex the country for its mineral wealth — in particular, rare earths. We are not wholly convinced that the US will send in the military (although not dismissing it either), but they are sending explorers to tap the country’s mineral wealth.

Can the West compete?

A rare earth supply chain outside China faces obstacles:

- High Capex

- Technical expertise

- Environmental regulations

- Price volatility

But government-backed price floors, streamlined permits, and guaranteed off-take contracts are starting to shift the dynamic in the West’s favor.

Japan, the canary in the rare earth mine

And it’s worked before. In 2010, after China implemented an export ban on rare earths against Japan following a territorial dispute, the country worked to diversify and secure its supply chains.

The strategy included investing in mines and processing in Australia — notably Lynas — as well as stockpiling, recycling and promoting alternative technologies.

As a result, Japan’s dependence on Chinese rare earths fell to 60% from 2023 from more than 90% in 2010.

Conclusion: can it work?

In short, this struggle over rare earth supply isn’t just a mineral market story. It’s a realignment of global economic power.

The West is finally treating rare earths as the strategic commodities they are. With price floors, equity stakes, export incentives, and regulatory overhauls, the foundations to significantly ramp up production are being put into place. Add geopolitical diversification and tech-sector capital, and the West finally seems serious at breaking China’s monopoly.

So, yes, Western (US) efforts to diversify from China can work — but only with sustained government and corporate alignment.

And there are already mixed signals across the industry.

For example, General Motors is reportedly planning to continue importing electric vehicle batteries from Chinese battery giant CATL for another two years as a “stopgap” until they can manufacturer their own. However, as we warn in our article on US automakers vs US miners: there’s nothing more permanent than the temporary.

Significant challenges remain: from timescales to built out supply chains, processing scale, environmental constraints, and cost competitiveness will continue to test feasibility.

Rare earths are the test: will the West commit the time and money to take on China? If yes, momentum will shift across the entire range of critical minerals. If not, the remaining Western critical mineral supply chains and their manufacturing stacks could break.

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.