Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

China controls a vertically integrated titanium empire – from ore mines and TiO₂ pigment plants to sponge and aerospace alloy production – giving it unprecedented influence over global prices and supply, but faces structural constraints that creates opportunities for Western suppliers.

A major US defense prime conducted a recent, rare deep trace of its titanium supply chain, reaching 13 tiers down — it led directly to “Chinese mines, Chinese roads, and Chinese trucks” as confirmed by their supply chain specialists, according Stanford’s recent Critical Minerals and the Business of National Security report.

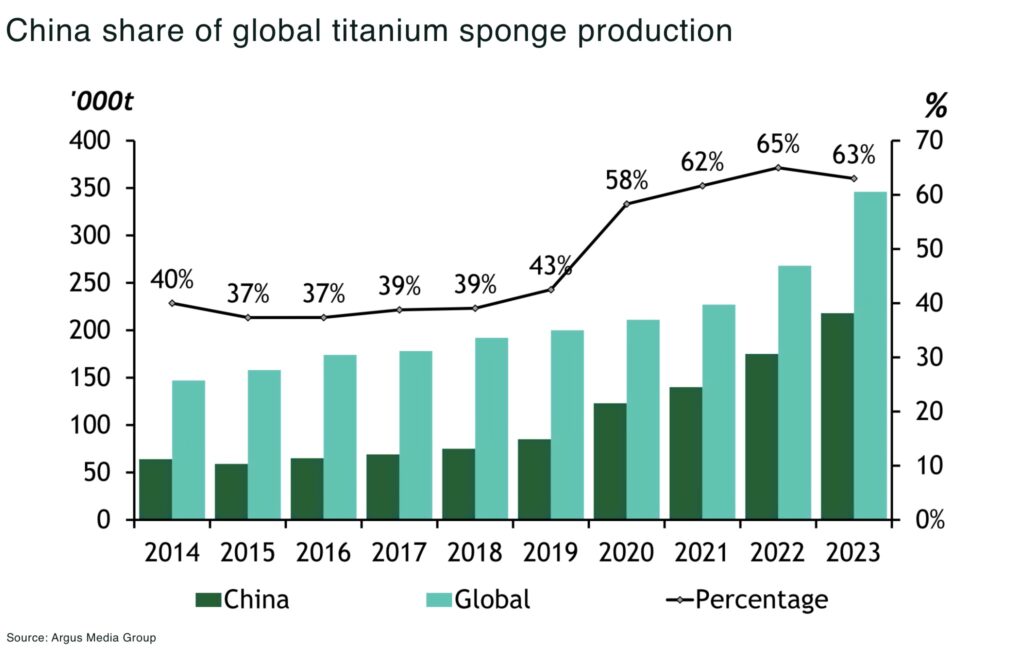

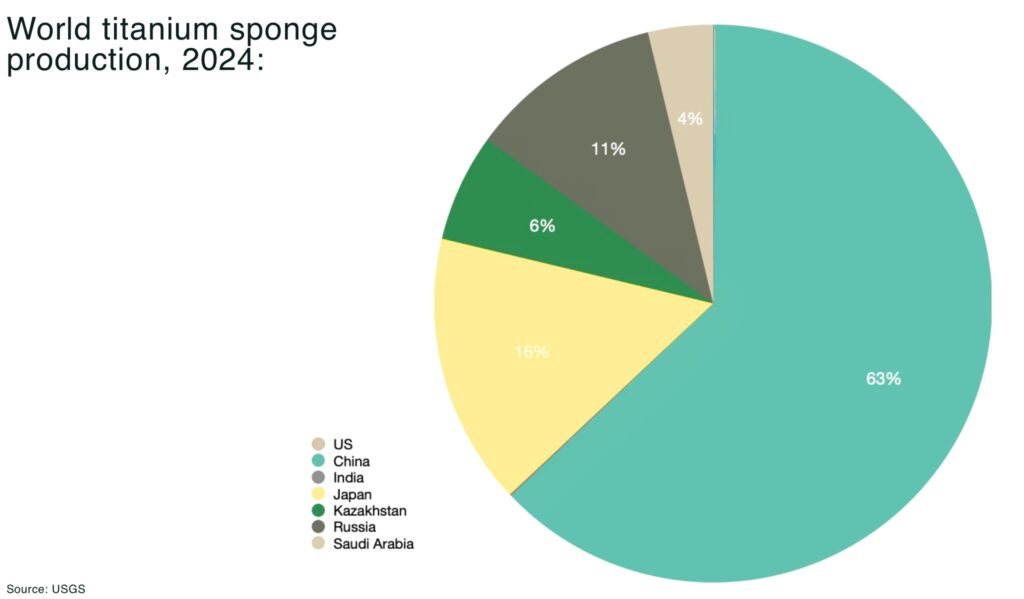

The example is indicative of China’s rising global titanium dominance so that, by 2024, China accounted for:

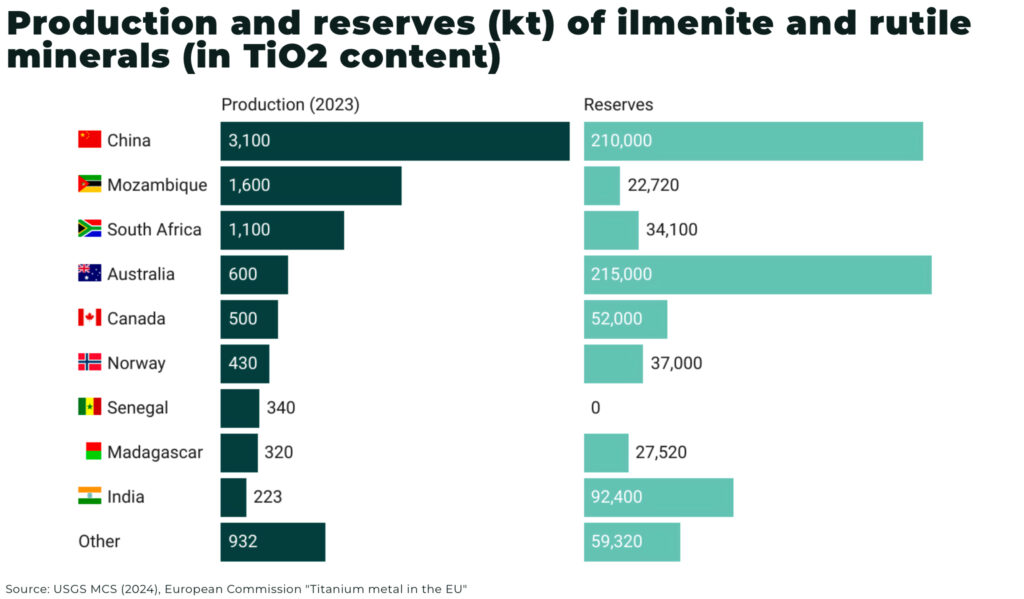

- 34%, the highest global producer, of primary titanium minerals, ilmenite and rutile

- and 67% of global titanium sponge production, with domestic sponge capacity around 320,000 t/yr in 2024 and rising

- in pigment, China’s TiO₂ production capacity reportedly reached 6.05 million tons by the end of 2024, with an additional 1.3 million tons planned for 2025, representing over 55% of global capacity

This scale allows Chinese producers to influence pricing across the entire titanium value chain. It’s a dominance that stems from cost advantages, scale, and integration.

But, a closer examination of China’s production reveals critical constraints across aerospace qualification, feedstock access, and market segmentation. This creates meaningful opportunities for Western and allied producers who are advancing trade defenses and supply chain diversification efforts.

What is titanium and why is it important?

Titanium is a lightweight, high-strength metal prized for its resistance to corrosion and extreme temperatures. It has the highest strength-to-weight ratio of any structural metal, about as strong as steel but 45% lighter.

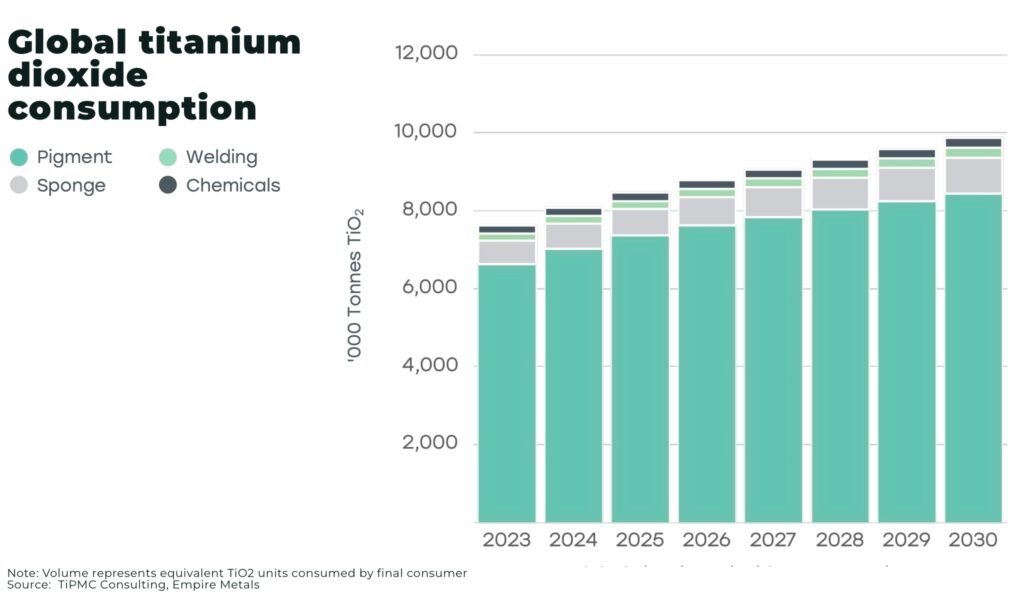

Titanium’s strength-to-weight ratio makes the metal indispensable across aerospace, defense, medical implants, and advanced manufacturing. Titanium alloys form the backbone of jet engines, airframes, and missile casings; titanium dioxide (TiO₂), its oxidized form, is used in paint pigments, coatings, and solar panels.

The US, EU, and Japan classify titanium as critical because it’s essential for military aircraft, naval vessels, and energy systems. Demand for titanium for aerospace engines alone is expected to grow at 10.5% CAGR over next 5 years, as just one example of its growing importance in parallel to an evolving defense sector. Another example of titanium’s critical role in defense, the US F-22 Raptor contains roughly 39% titanium by weight.

Yet, titanium is concentrated in only a few supply chains.

China’s vertically integrated titanium supply chain — and its limitations

China has built end-to-end, near self-sufficiency, in the titanium supply chain, controlling every step from raw minerals to high-end products, but faces critical barriers to aerospace qualification and domestically-constrained mineral resources.

Over the past 20 years, Chinese companies have expanded aggressively into mining heavy mineral sands (ilmenite) and hard-rock titanium deposits, then integrating upstream into pigment factories, sponge plants, and even finished alloy component manufacturing.

This vertical integration means China can mine titanium and internally upgrade it through each stage: concentrate → TiO₂ pigment (for paints, plastics) → titanium sponge → melted alloys and mill products for aerospace and industry.

To illustrate China’s scale:

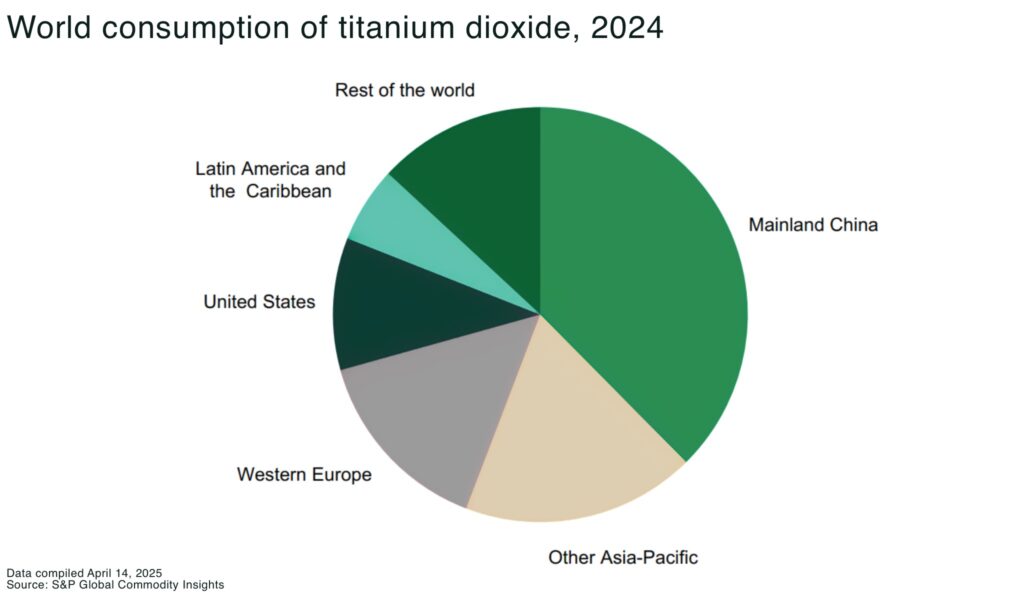

- nearly 90% of all mined titanium ends up as TiO₂ pigment, and China has become the largest producer and consumer of these pigment feedstocks by far

- as of 2024, China’s titanium sponge capacity was 260,000 tonnes – about 63% of global capacity. This dwarfs the capacity of Japan (15%) or Russia (11%)

China’s feedstock dominance is backed by both domestic mines (eg in Sichuan, Hebei, Hainan provinces) and strategic offtake agreements abroad. Chinese firms have been investing in African mineral sands projects, and the state-owned China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) secured stakes in ilmenite mines to guarantee ore supply.

China’s integration is equally comprehensive in titanium metal. Chinese companies operate multiple sponge plants (titanium sponge is the porous metal from Kroll/Hunter processes), which feed into domestic melting facilities that produce ingots, billets, and finished titanium parts.

In short, China’s vertical integration has transformed titanium from a once somewhat dispersed global supply chain into one increasingly centered on China.

Cost advantages: why China produces titanium cheaper

China’s titanium industry operates at a structural cost advantage driven by cheap inputs, scale, and lighter regulation, including:

- labor and compliance: industrial wages are 70–80% lower than in the West. Environmental controls cost have been historically lower across than EU/US levels (the sulfate-process pigment creates large amounts of acidic waste and iron sulfate byproduct)

- cheap chemical and energy input: costs of chlorine and sulfuric acid are significantly cheaper in China; electricity is also cheaper and state-subsidized

- scale economies: mass production in China yields economy of scale benefits in procurement and operations while, for example, Japan’s relatively smaller-scale plants struggle to compete

Critical constraint: aerospace qualification and feedstock limitations

However, there is a critical caveat often overlooked: most Chinese titanium sponge and mill products are NOT qualified for Western aerospace and defense applications. This is not accidental — it reflects deliberate quality standards, ITAR restrictions, and technical certifications that Western aerospace manufacturers require.

In aerospace and defense, only high-quality sponge from qualified sources can be used; impurity levels and consistency are critical. Most titanium sponge exports from China do not meet stringent Western aerospace specifications and are either unavailable for export due to security restrictions or simply do not qualify under customer specifications (e.g. BAE, Airbus, Boeing, Lockheed Martin specifications). Thus, the 67% market share in global sponge production does not translate into dominance in aerospace-grade sponge — a critical distinction.

This certification and qualification bottleneck means that even though China has sponge capacity to spare, Western aerospace manufacturers cannot easily use it. The West must therefore continue to rely on qualified suppliers, primarily Japan’s producers (Toho Titanium and Osaka Titanium) and, where possible, non-sanctioned CIS ((Russia, Kazakhstan, Ukraine) suppliers.

China’s hidden vulnerability

A second, underappreciated constraint: China’s significant titanium reserves are mostly titano-magnetite and rock ilmenite — neither of which can be used directly in sponge production or chlorination processes. These materials require intermediate conversion steps to become usable feedstock.

China relies on importing raw titanium concentrates to satisfy its downstream sponge and pigment plants. However, this import dependency is becoming increasingly precarious as global governments push back on exporting the value of their natural resources to China. Raw concentrate pricing has been rising, and exporting countries (Australia, African producers, etc) are under pressure from their own governments to capture more of the downstream processing for greater value-add.

This creates a structural vulnerability for China’s dominance: while China controls massive sponge and pigment capacity, it is not vertically integrated at the feedstock level in the way often assumed.

The bifurcated TiO₂ market: China dominance in commodity segment, Western opportunity in specialty

One of the most underappreciated dynamics in titanium is the deep bifurcation of the TiO₂ market, and China’s saturation in the commodity segment.

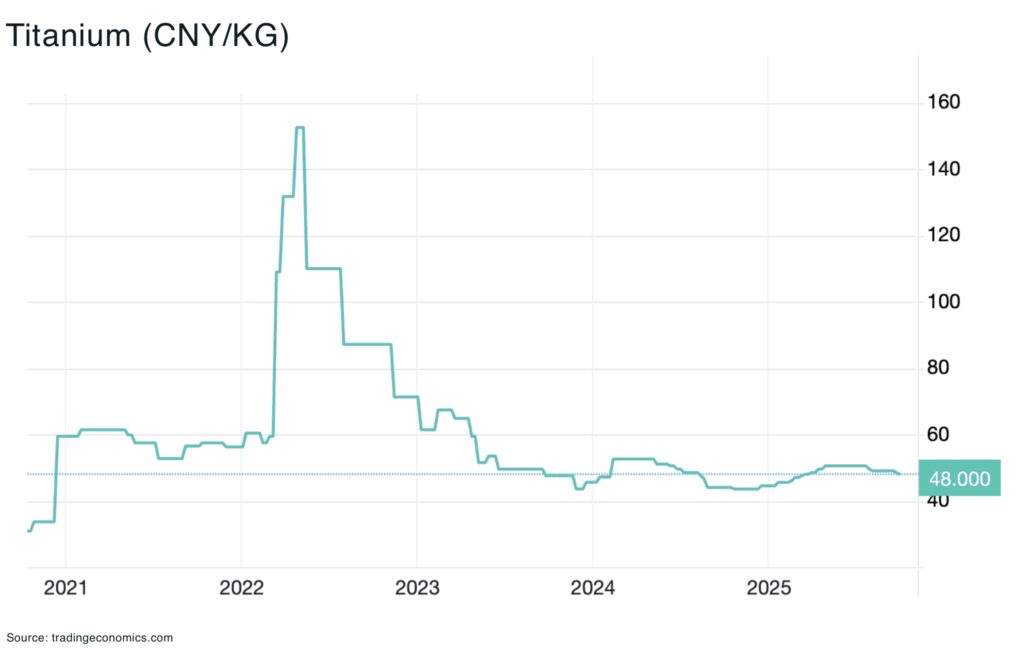

China’s market share gains have coincided with significant price swings. During 2021–2022, TiO₂ pigment prices spiked as post-pandemic demand surged. This coincided with some supply constraints (including Western production issues), and major producers like Chemours and Tronox pushed through price increases.

However, Chinese exporters aggressively targeted overseas markets (e.g. India and Brazil) during 2022–2023, when domestic demand slowed (primarily due to China’s property downturn and COVID lockdown effects), removing “value” from the market by undercutting prices which had risen 12.9% year-on-year. According to analysis by JPMorgan, 400,000 tons of TiO2 was exported annually by China to India and Brazil (markets where antidumping duties now exceed $500 per ton) pricing out competition. And, as new Chinese sulfate plants came online and exports rose, the supply-demand balance shifted to surplus by late 2022. The result was a steep decline in pigment prices through 2023 and 2024.

Chinese TiO₂ is predominantly sulfate-process material (approx 81% of China’s TiO₂ exports in 2024), which is lower-cost, lower-grade, and suitable for commodity coatings, plastics, and paper applications. Sulfate-process pigment does not require the high-grade feedstock (natural rutile, synthetic rutile, or chloride slag) that chloride-process pigment demands.

Western TiO₂ producers (Chemours, Kronos, Venator, Huntsman) operate primarily via the chloride process, which produces a higher-purity, higher-performance pigment suitable for aerospace-grade coatings, high-performance automotive finishes, and specialty applications. Chloride-process pigment commands a significant premium over sulfate-process material.

This market bifurcation means:

- Chinese players dominate the commodity segment with massive volume at lower margins

- Western players retain meaningful share in the specialty/high-performance segment, expected to grow, at higher margins and better pricing power

- the two markets are not direct competitors for all applications

The key competitive pressure is in the commodity segment, where Chinese exporters have flooded markets and undercut pricing — triggering an anti-dumping response across the world.

China’s market share and global pricing backlash

By flooding the market, Chinese producers have acted as global price-setters at the margin.

The effects of Covid (a demand crash in 2020, then restocking boom in 2021) exacerbated price swings, but it was Chinese expansion that turned what could have been a recovery into a glut.

Recent titanium/TiO₂ / Sponge / processing closures and idlings in West

| Entity — Location | Closure / Idling Year | |

| TIMET / Henderson, NV, USA – US sponge plant | 2020 | The last active titanium sponge producer in US, with the capacity to meet 100% of US military titanium sponge needs |

| ATI / Albany, Oregon, USA– Titanium / alloy facility | 2020 | Vital in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allegheny_Technologies |

| Venator (UK) – Pori pigment plant, Finland | 2021 | One of Europe’s largest and most technically advanced facilities for specialty TiO₂ pigments |

| Eramet / Tyssedal— Norway | 2020 | A key European ilmenite upgrading site |

| Zaporozhye Titanium & Magnesium— Ukraine | 2022 | The only titanium sponge facility in Europe, representing about 7% of global titanium minerals output |

The West wakes up to the challenge

By late 2024, Chinese pigment exports were facing headwinds — in particular, multiple countries, including some of its largest titanium export markets, started to implement anti-dumping duties:

- EU imposed anti-dumping tariffs (14.4%–39.7%) on TiO₂ imports from China in 2025

- Brazil set duties of US$578–$1,772/ton

- in 2025, India imposed anti-dumping duties on imports of TiO₂ from China, ranging from US$460-681 per metric ton

- and Saudi Arabia launched their own anti-dumping investigations in 2024

The tariffs have had a significant impact in neutralizing the price advantage of Chinese imports, with analysts forecasting a tentative price recovery in 2025; for example, Chemours, one of the world’s leading titanium dioxide suppliers, announced it will impose a 125% tariff surcharge on products exported to China, effective May 1, 2025 — and that the hike stems from steep cost increases due to China’s counter-tariffs.

However, the current structural reality is that China, by commanding such a large share of production, will continue to heavily influence global titanium prices.

China’s strategic circumvention via acquisition

Importantly, Chinese producers are not sitting passively. Recently, Chinese firms have acquired strategic assets in Europe to circumvent tariffs and secure process know-how. For example, Chinese buyers have acquired the Greetham assets in the UK, which include significant product and process intellectual property, as well as an established European footprint that allows Chinese companies to legally operate within the EU tariff structure, effectively circumventing Western trade defenses.

Choke points: sponge, feedstocks, and Western scale-up barriers

Two major chokepoints stand out: titanium sponge production (crucial for aerospace/defense alloys) and high-grade feedstock for chloride pigment and aerospace metal (natural rutile, synthetic rutile, and chloride slag).

These are areas where capacity is concentrated or inherently hard to scale, and where Western nations have found themselves at a disadvantage.

China’s increasing implementation of export restrictions across a range of critical minerals, from rare earths to antimony, gallium to germanium, has raised alarms about potential future restrictions on titanium.

Bob Wetherbee, president of Dallas-based ATI, one of the three big producers of US titanium metal, recently told the Washington Post that he believed all of the American titanium producers had seen demand double, but that “the lack of action is having an impact on national security.”

Titanium sponge

Sponge production, used to produce ingots for aerospace-grade titanium, is limited to a handful of countries, due to the capital-intensive and energy-intensive nature of the Kroll process and the need for handling hazardous chemicals.

70-80% of the world’s sponge is produced by China and the CIS, with Japan making up most of the rest. As of May 2025, the US had only one titanium sponge producer in Utah with a capacity of 500 tons per year; in 2023, the US imported 42,000 tonnes of titanium sponge. This means the US and many allies rely entirely on imports, primarily from Japan’s producers (Toho Titanium and Osaka Titanium) and Kazakhstan’s UKTMP, as Russian sponge is now largely off-limits due to sanctions.

This concentration of sponge supply is a strategic vulnerability to any disruption (whether incidental or accidental). The US Department of War has identified titanium sponge as a “potential single point of failure” in the defense supply chain as far back as 2018.

Building a new sponge plant or expanding an existing one takes years and hundreds of millions of dollars, with many companies hesitant and limited by resources to even expand capacity.

As stated, in aerospace and defense, only high-quality materials from qualified sources can be used as impurity levels and consistency are critical — this is the case for titanium sponge, and most of titanium sponge exports from China are not certified for Western aerospace, a deliberate barrier (for quality and security reasons). This certification bottleneck means even if China has sponge to spare, Western aerospace manufacturers can’t easily use it unless it meets stringent standards and ITAR-like restrictions can be navigated. Thus, sponge remains a choke point for the West – ample globally, but not all of it accessible.

High-grade feedstock shortages

The second choke point is at the opposite end of the chain: titanium feedstocks, specifically high-grade forms (natural rutile, synthetic rutile, and chloride-grade slag).

While ilmenite is abundant, truly high-TiO₂ feedstocks are relatively scarce and geographically concentrated. These are crucial for two things: chloride-process pigment (which requires feed ~90% TiO₂ or above for efficiency) and titanium metal production (sponge plants ideally use ultra-high-grade feed like rutile to avoid contamination).

Historically, natural rutile (95%+ TiO₂) came from only a few countries: Australia (especially Iluka’s mines in the 2000s), Sierra Leone, Ukraine, and a bit from South Africa and Kenya — but, output has been declining or stagnant:

- Iluka has noted diminished resources in its once-rich Australian rutile mines

- Sierra Leone’s rutile (Sierra Rutile Ltd) has struggled with operational issues and civil unrest

- and Ukraine’s large rutile production (from Irshansk and Vilnohirsk) nearly vanished in 2022 due to the war

In 2022, global natural rutile production was approx 0.65 million tonnes, not nearly enough to satisfy all chloride pigment and aerospace needs. Synthetic alternatives like upgraded titania slag (UGS) and synthetic rutile (SR) are also limited.

This means Western chloride pigment producers (Chemours, Kronos, Venator) often find themselves short of high-grade feedstock. They must compete for rutile or SR, driving the cost up.

Chinese pigment producers instead mostly use the sulfate process (over 80% of China’s TiO₂ output is sulfate-route), which uses ilmenite to avoid this high-grade feed dependency.

Without sufficient rutile or SR, Western chloride plants can’t run at full rates. In 2022–2023, some had to curtail output due to feedstock shortage and price spikes (rutile prices hit multi-year highs post-Ukraine invasion, as consumers scrambled to replace Ukrainian supply).

The choke point is even more acute for titanium metal producers. Sponge plants ideally want very pure feed (natural rutile or equivalent) to minimize impurities in the metal. The US has historically relied on Australia and others, but with Iluka’s rutile production grade declining and more rutile being diverted to pigment, the aerospace industry is facing a structural shortage of premium rutile-grade feed.

The supply of high-grade titanium feedstock is a hard constraint that limits both pigment production (West) and potential expansion of titanium metal production outside China.

Global natural rutile production was only about 0.63 million tonnes in 2022, insufficient to meet combined demand from chloride pigment and aerospace manufacturers. The limited supply drives competition among major Western chloride-route producers (Chemours, Kronos, Venator) for high-grade feed (natural rutile, synthetic rutile/SR, or upgraded titania slag/UGS).

Chinese titanium dioxide (TiO₂) producers mitigate this high-grade feed dependency by primarily using the sulfate process, which relies on more abundant, lower-grade ilmenite. This operational choice is reflected in China’s trade data, where approximately 81% of its total TiO₂ exports in 2024 were sulfate-process material.

The limited supply of high-grade titanium feed constrains the operating rates of Western chloride-route pigment plants and limits potential expansion of titanium metal production outside of China.

Strategic outlook for the West

The genuine strategic opportunity lies not in attempting to compete with China in commodity pigment production, but in developing alternative, lower-cost feedstock pathways that can serve both the TiO₂ industry and, critically, new sponge production initiatives.

If the West wants to counter Chinese dominance, then quite simply it needs to produce more titanium. The big question is: can the US and allies realistically challenge China’s titanium supremacy, or at least mitigate the risks, within the next decade?

Reshoring and critical mineral strategies

The US, EU, UK, Japan, and Australia have all listed titanium under their critical mineral lists, meaning it’s recognized as essential and at risk of supply disruption — and has been followed up with some government policy and investment:

- funding and incentives: the US Department of War, through the Defense Production Act (DPA) Title III program, has issued contracts and grants to encourage domestic titanium production. For example, IperionX, a US startup, received a contract of up to US$47.1 million to establish a titanium supply chain using novel methods. IperionX is working on mining titanium minerals in Tennessee and producing titanium powder via a new process. Similarly, the DoW has funded research into extraction of titanium from ores with lower cost and energy

- trade policy: Western nations have already shown themselves willing to use tariffs and trade defenses to protect remaining producers from unfair competition. This is likely to continue; for example, the EU’s anti-dumping duties on Chinese pigment will run for 5 years and could be renewed

- allied cooperation: there is talk of an “allied titanium network” where friendly countries coordinate. For instance, Japan could supply sponge to the US, while the US supplies alloy scrap to Japan. Likewise, Australia and the US have an agreement on critical minerals that could facilitate Australian feedstock being processed in the US with DoW support

- The US National Defense Stockpile has also been authorized to acquire titanium (sponge or alloy) to ensure a buffer. In 2022, the US stockpile was essentially at zero for titanium; now appropriations have been made to stockpile some material, which means government purchases supporting non-Chinese suppliers

- environmental and permitting reform: some Western countries are working on faster permitting for critical mineral projects. If, for example, a new mineral sands mine is proposed in the US or an expansion in Australia, governments are increasingly likely to streamline approvals

Diversification via new projects: Empire Metals

To counterbalance China’s control, Western countries and others are exploring new titanium feedstock projects as potential game-changers. Several notable developments – from Australia’s giant Pitfield discovery to new mineral sands mines in Africa – could provide alternative sources of titanium by the 2030s.

Here we highlight Empire Metals’ Pitfield project:

Empire Metals’ Pitfield (Australia)

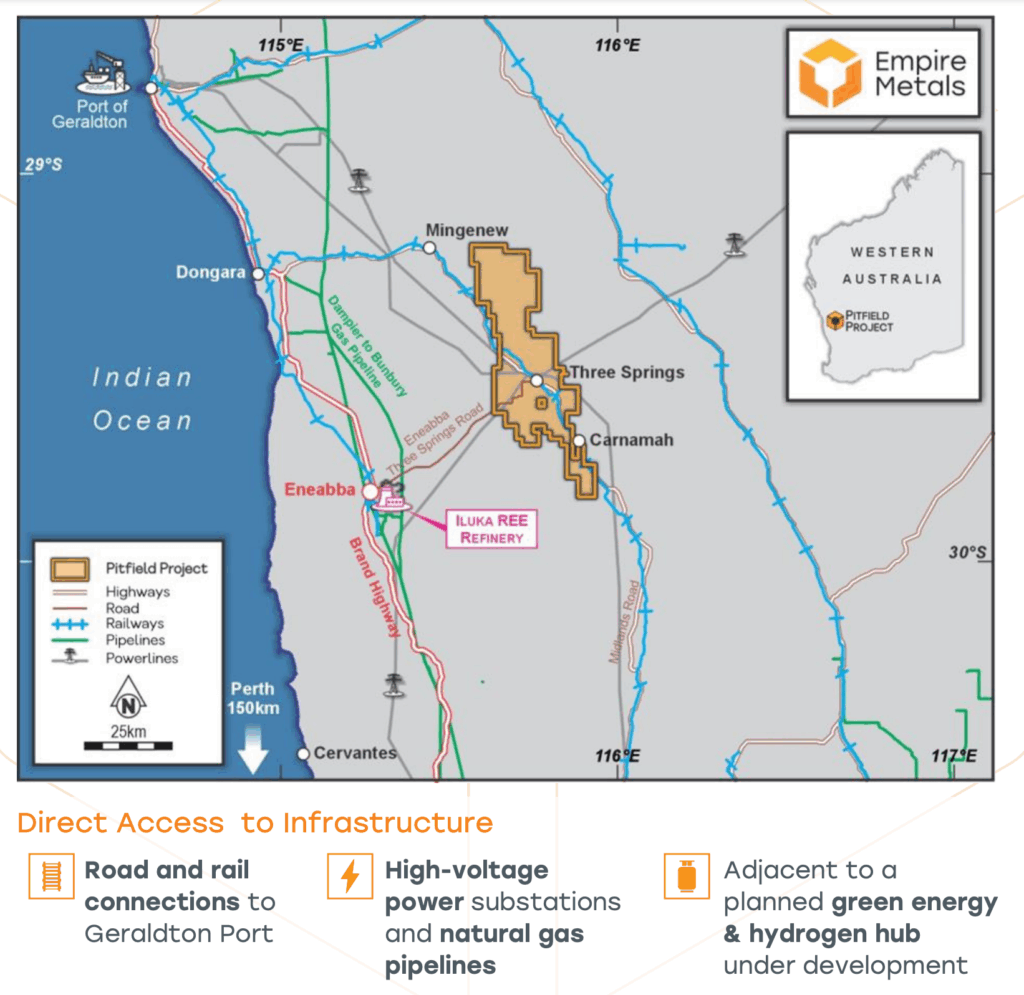

Empire Metals (LON: EEE OTCQX: EPMLF) is accelerating the economic development of its flagship Pitfield project — one of the largest known and highest-grade titanium discoveries in the world — extending over 40km x 8km x 5km deep.

In 2023–2024, Empire Metals announced that drilling at Pitfield outlined an enormous titanium mineral system across a broad area. The company reported a Mineral Resource Estimate (MRE) totalling 2.2 billion tonnes grading 5.1% TiO₂ for 113 million tonnes of contained TiO₂. For context, most existing ilmenite mines are on the order of tens of millions of tonnes of ore. Titanium mineralization at Pitfield occurs from surface and displays exceptional grade continuity along strike and down dip. The MRE extends across just 20% of the known mineralized footprint, providing substantial potential for further resource expansion.

The titanium at Pitfield is in the form of disseminated high-grade anatase (known for its very high TiO₂ content and bright whiteness, making it particularly attractive for premium pigment, coatings, and advanced industrial applications) and rutile in near-surface saprolite (weathered rock) . Empire achieved up to 99.25% TiO₂ purity product in laboratory tests from this material, indicating it can produce a high-grade product suitable for pigment or even titanium metal feed.

Importantly, the project is located in Australia’s mid-West, a Tier One mining jurisdiction with direct access to critical infrastructure:

- existing road/rail network

- proximity to Geraldton Port (150km)

- low-energy processing advantages from weathered cap mineralization (30–40m depth)

Empire is focused on accelerating the economic development of Pitfield, with a vision to produce a high-value titanium metal or pigment quality product at Pitfield, to realise the full value potential of this exceptional deposit — and potentially shift market dynamics in the 2030s.

All these efforts will take time to bear fruit. But by the 2030s, we could see a patchwork of revived capabilities: perhaps a small titanium sponge facility in the U.S. (even if just pilot scale for defense needs), more heavy mineral mines in allied countries, and closer integration between allies (like Japan-U.S. tech sharing for efficient processing). The ultimate goal is not necessarily to displace China’s industry, which would be unrealistic, but to have enough independent capacity and reserve stock to not be beholden to China in a crisis. Titanium’s strategic importance (for fighter jets, missiles, satellites, naval vessels, EV components, and more) means that dependency is a security liability.

Conclusion: towards more multipolar titanium world?

From a strategic standpoint, the goal for the West is not necessarily to surpass China, but to ensure a resilient, secure supply chain. By 2030s, success would mean ensuring enough domestic and allied supply of sponge for defense needs, enough pigment supply options, and a diverse set of mines globally so a disruption in one region cannot cripple industries.

We expect a more multipolar world:

- China is, and will remain, a heavyweight across all titanium sectors into the 2030s

- Russian capacity, dependent on geopolitics, could potentially return to global markets

- and new supply across secure regions in the West alliance, such as Empire Metals in Australia, to come online.

In particular, TiO₂ players with chloride-process expertise and access to alternative feedstocks emerge as strategic partners in ensuring supply chain resilience.

The US and allies are now actively working to reshape the titanium supply chain through targeted investment, allied cooperation, and strategic project development. Projects like Empire’s Pitfield, combined with TiO₂ industry innovation and government-backed sponge initiatives, have potential to be genuine game changers that help build a more resilient, multipolar titanium supply ecosystem.