- agriculture industry worth estimated US$5 trillion

- 49 million people in 46 countries at risk of falling into famine

- America exported a record US$177 billion farm and food products in 2021

- a record US$10.5 billion invested into Agtech in 2021, studies suggest this could double by 2025

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

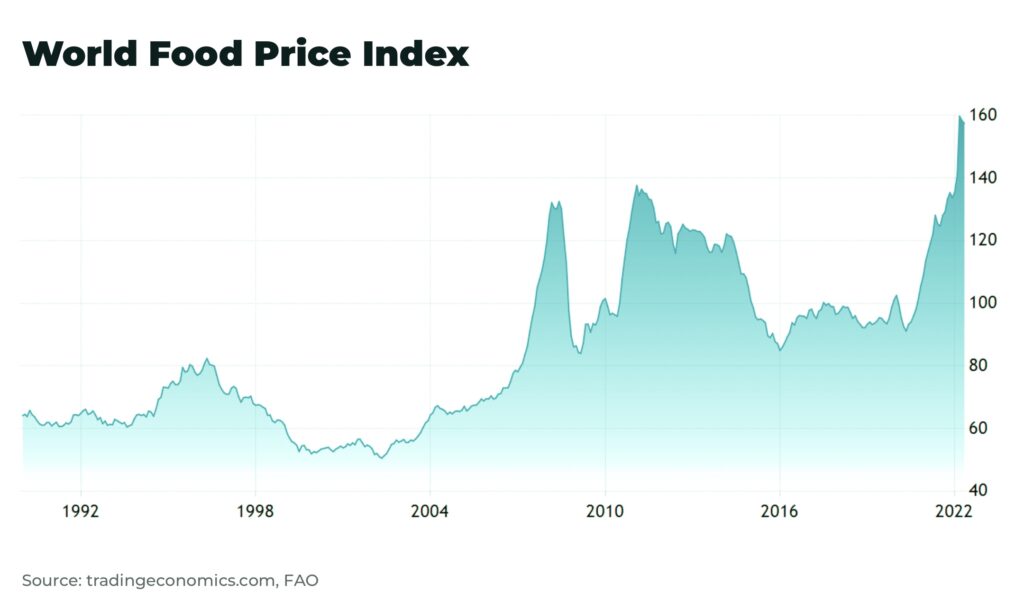

As a series of crises spike food prices, threatening economic and political stability across the world, new opportunities in the enormous and complex global food and agriculture industry — worth an estimated US$5 trillion — are opening up. So where should investors even start?

Firstly, why are food prices rising so dramatically?

Coronavirus lockdowns severely strained supply chains, creating a shortage of labour and restricting the transport of food produce, including higher freight costs, from farms to markets.

Then, when Russia invaded Ukraine, world food commodity prices hit their highest levels ever. The two countries account for nearly a third of global wheat supplies, as well as other major commodities like sunflower oil. The war has not only disrupted regional agricultural production but Russia’s blockade of the Black Sea ports means an estimated 20 million tons of wheat and corn are trapped.

And nowhere else is able to take up the slack. China’s wheat harvest is being described as the “worst in history” after heavy rains, a record-breaking heatwave in India has hit their wheat growing regions prompting an export ban, and crops in the US, Canada, Brazil and other countries have also been hit by extreme weather.

Rising energy prices (see our analysis on the spiking oil price) — necessary for everything from production to transport, refrigeration to natural gas for fertilizer — are also pushing up food prices.

Then there’s the soaring cost of fertilizer. Russia and neighbouring Belarus, which allowed Russia to invade Ukraine from its territory, combined accounted for over 40% of global potash exports last year. Their potash exports have now also been sanctioned and this matters because potash is a key ingredient for fertilizer, so threatening future crop yields.

“We are deeply concerned about the combined impacts of overlapping crises jeopardizing people’s ability to produce and access foods, pushing millions more into extreme levels of acute food insecurity.”

QU Dongyu — The Food and Agriculture Organization, Director-General

“We are deeply concerned about the combined impacts of overlapping crises jeopardizing people’s ability to produce and access foods, pushing millions more into extreme levels of acute food insecurity,” warned FAO Director-General QU Dongyu.

The latest UN report warns “an all-time high of up to 49 million people in 46 countries could now be at risk of falling into famine.” Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Sudan and Yemen are on the “highest alert” as hotspots with potentially catastrophic conditions. Congo (DRC), Haiti, the Sahel, Sudan and Syria are of “very high concern.”

As populations across the globe struggle with the rising prices of basic necessities, politics in almost every country are anticipated to be affected. Food protests are already underway in Iran; northern Nigeria risks famine just as the oil-producing country is about to enter a tense election period next year; Pakistan is slashing spending to convince the IMF to resume its loan program to the country; President Macron has lost his parliamentary majority as the cost of living surges; and, if these examples seem relatively remote, just look at Joe Biden’s recent approval ratings.

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

Emerging markets, in particular, are a significant risk but every country will be affected differently and have different reactions — a fallout so complex we at The Oregon Group expect to be positioning for some time to come — but, for now, let’s look at one example to highlight the issues at hand:

Egypt, a key security partner in the Middle East and North Africa for the West with control over the Suez Canal, is the world’s biggest wheat importer, largely from Ukraine. Over 70% of the population is dependent on the state’s food subsidy program. Yet, wheat cargoes, when they are able to leave Ukraine, currently have to be transported by train via Eastern Europe because of the Black Sea blockade. What sort of knock-on effect will this have? Well, consider that just ten years ago, Tahrir Square in Egypt’s capital Cairo was arguably the heart of the Arab Spring protests that sent shockwaves across the Middle East and North Africa.

Egypt and most other countries have enough food reserves and contracts to see them through this year. But, by next year, their reserves will be largely tapped out and, if the issues of supply chains, food bans and fertilizer shortages are not resolved, the food crisis could become acute.

Even if these geopolitical shocks are resolved, the timeframe for this crisis is long-term.

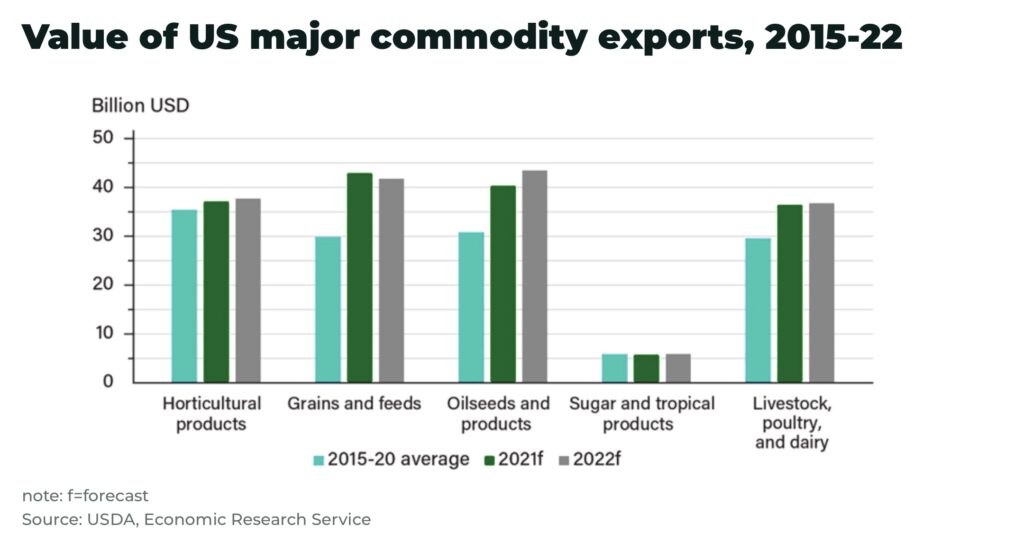

So, as an investor, how should you be thinking about all of this? Well, agricultural commodities, fertilizer and food companies in the large food production centers (the US, Canada, the EU) are an obvious starting point. Record inflation and the risk of recession may change some spending habits, but people still need to eat.

North America is already seeing a serious uptick in agricultural output and prices. The US, last year, posted its highest farm and food product export levels ever recorded, over US$177 billion, growth of 18% from 2020. The country still has capacity for significant agricultural growth.

In Canada, the world’s largest potash exporter accounting for over 30% of global exports, stock prices for fertilizer companies spiked after the Ukraine invasion.

We also expect to see investors and companies will bringing money back home to capitalize on high prices, a further blow to globalization (listen to our podcast on deglobalization). They will be encouraged to do so by governments with no money to spare after the Covid lockdowns and desperate to reduce their supply chain risk.

This trend is already underway.

For example, Singapore imports 90% of its food and in 2019 announced plans to triple domestic food production by 2030. But how is this possible for a country 170 times smaller than New York City with less than 1% of its land area used for agriculture?

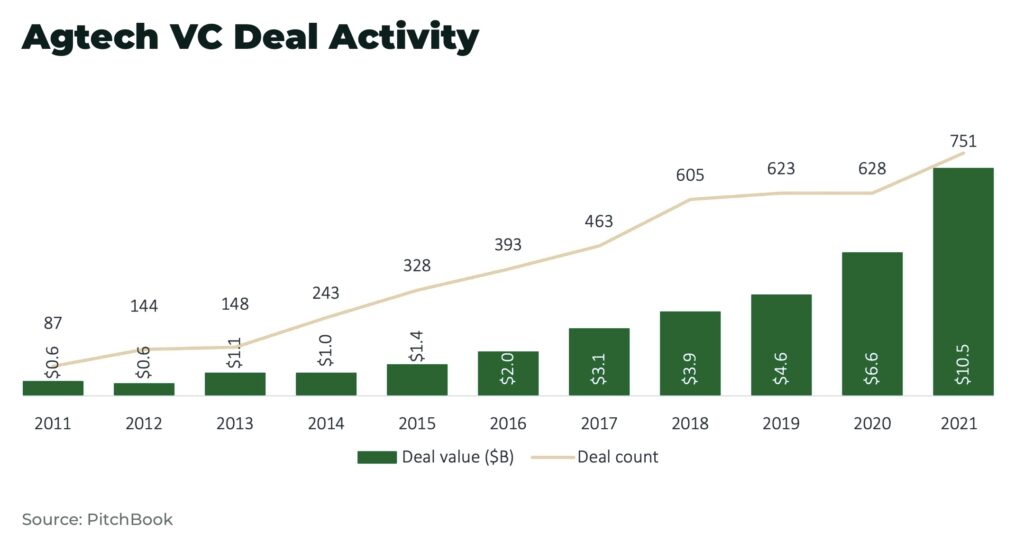

Investments in the latest technological advancements in agriculture offer some of the most promising upside in the current crisis.

Vertical farming allows crops to be grown in tight spaces, for example on urban rooftops. Agricultural technology, or agtech, such as plant genetics, is allowing crops to be grown faster. Innovative greenhouses optimize irrigation, temperature, air filtration. Robotics for surveillance and artificial intelligence for faster processing of data and implementation of new techniques. And all of these techniques promote sustainability, recycling, cutting down on waste and carbon emissions, and so supporting the fight against climate change and its impact on agriculture.

Last year, a record US$10.5 billion was invested into agtech. One study from Juniper Research suggests the market value will reach US$22.5 billion by 2025.

The Netherlands, almost three times smaller than New York City, is one of the world’s largest agricultural producers, exporting over US$65 billion worth of food products in 2021. This was achieved as one of the world’s leaders in agtech.

Food prices are rising but, for investors and the fight against world hunger, the cupboard is not empty.

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.