Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

- Finite reserves: identified gold reserves total approx 59,000 tonnes worldwide —only about 20 years’ worth of mining at current production rates

- Dwindling supply pipeline: large gold miners’ reserves shrank approx 26% from 2012-2017. No major new gold deposit was discovered in 2023 or 2024

- Exploration gap: global exploration budgets fell 15% in 2023 and recent gold discoveries are smaller (avg. approx 4.4 Moz since 2020, vs 7.7 Moz a decade ago)

- Explorers’ key role: major producers have cut greenfield exploration and increasingly rely on junior explorers to find new deposits

When will the world run out of gold?

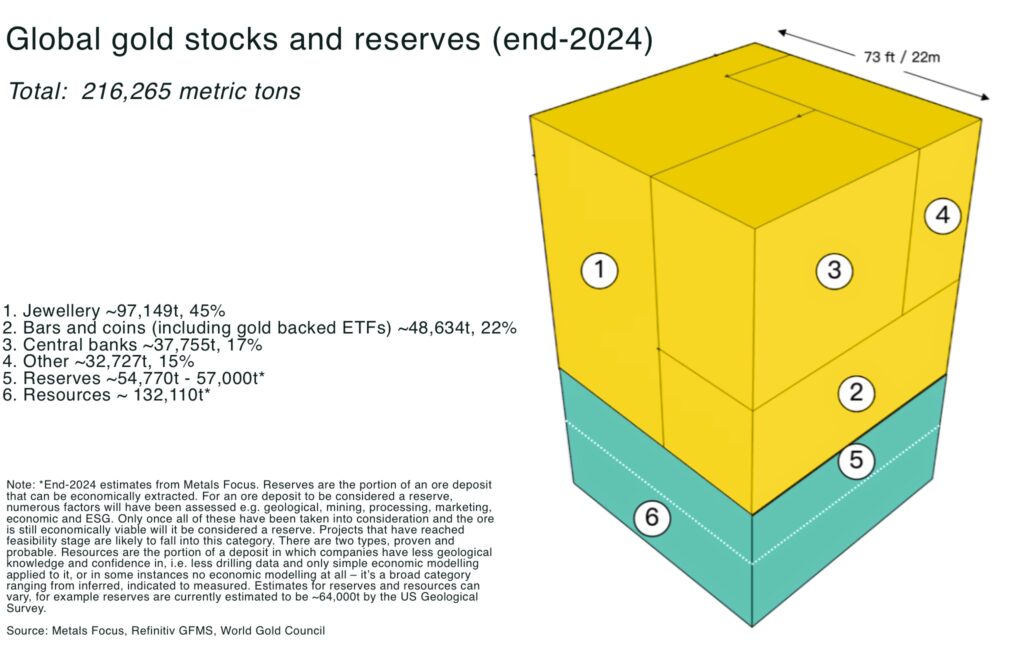

Gold is a finite resource in the Earth’s crust. The US Geological Survey estimates that only 54-57,000 metric tons of identified economic gold reserves remain globally. At the current annual mining rate of roughly 3,000–3,300 tonnes, those known reserves would be exhausted in less than 20 years.

In other words, if no new reserves are found, mineable gold could be largely gone by around 2040-2050.

Global mine production has essentially plateaued over the past 5–7 years. Many of the richest historical gold regions are in decline. South Africa’s Witwatersrand Basin, which alone has yielded an estimated 30-40% of all gold ever mined, saw annual output fall from a 1,000 ton peak in 1970 to just 157 tons in 2017. At current extraction rates, South Africa has maybe about 39 years of accessible gold reserves left. Likewise, other once-prolific gold belts – the Carlin Trend in Nevada and Australia’s Kalgoorlie “Super Pit” – are facing depleting reserves after decades of intensive mining — underscoring a looming supply cliff.

It’s important to note this doesn’t mean the world will literally run out of gold in 2050 – gold is almost infinitely recyclable — but it does mean that new discoveries of gold deposits are critical.

Meanwhile, demand for gold is soaring. In 2024, central banks worldwide bought an estimated 1,045 tonnes of gold, following 2022’s record 1,136 tonnes (the highest on record, back to 1950s) added and another 1,050t in 2023 — as banks and investors seek a hedge amid geopolitical tension and inflation, driving gold prices to all-time highs above $4,000 per ounce this year.

If new gold supply cannot keep pace with demand, the fundamental supply-demand imbalance could worsen, potentially driving prices even higher and spurring strategic concerns for key industries and central banks.

Gold Supply Crunch: World gold reserves are 59,000 tonnes (≈20 years of mining left). Global mine output has flatlined since the mid-2010s even as demand surges. South Africa, once a #1 producer, now mines 84% less gold than in 1970. A cautionary tale of resource depletion.

Why are new gold discoveries drying up?

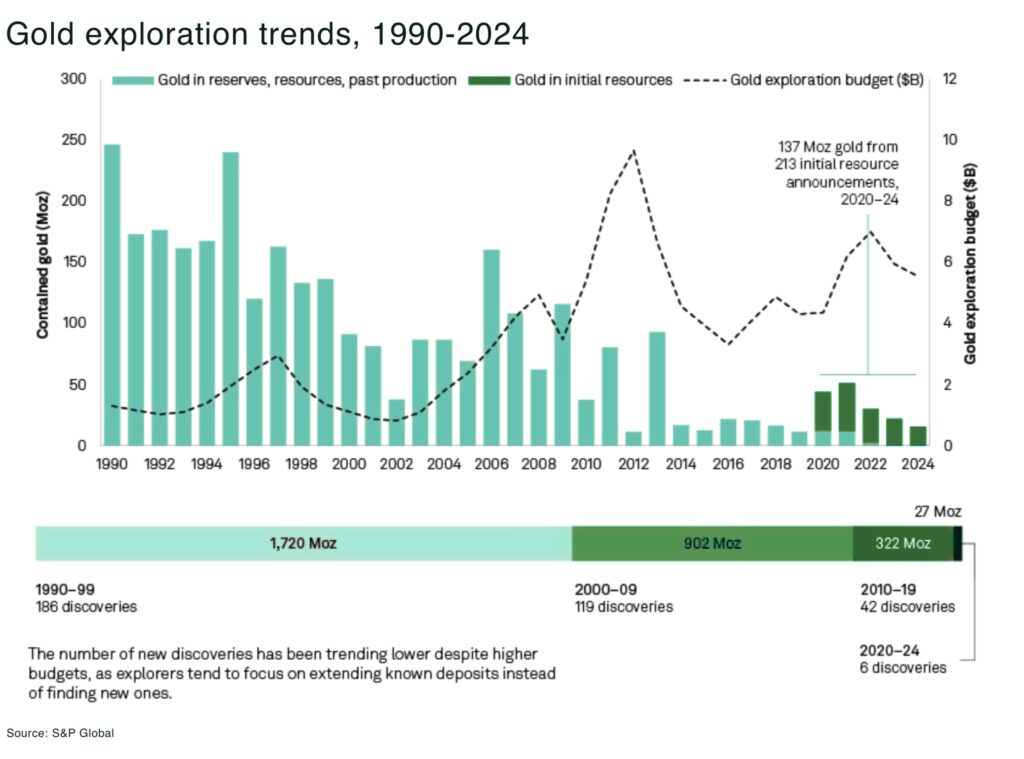

Despite record gold prices, new gold discoveries have fallen to a trickle. According to S&P Global data, no major gold deposit (≥2 million ounces) was discovered worldwide in 2023 or 2024.

In fact, since 2020, only six significant gold discoveries have been recorded, adding only 27 million ounces in combined reserves, a tiny fraction of the gold produced in that period.

By comparison, in earlier decades prospectors were finding much larger deposits regularly. In the 1970s–1990s, at least one super-giant (50+ Moz) gold vein and a dozen 30+ Moz deposits were discovered each decade. Since 2000, none of that scale have been found.

Crucially, exploration spending has not kept up or is misallocated. After gold’s last price peak in 2011, the industry slashed exploration budgets during the downturn. Majors went from spending about US$10.5 billion on exploration in 2012 to just US$3.2 billion in 2016. Although budgets recovered with rising gold prices (hitting US$7 billion in 2022), they have since pulled back again. In 2023, global gold exploration spending dropped 15%, followed by another 7% decline in 2024.

The number of new discoveries has been trending lower despite higher budgets, as many explorers tend to focus on extending known deposits instead of finding new ones. This retrenchment is primarily due to tighter financing for junior explorers, as interest rates and risk aversion tightened funding for many small mining ventures.

Only 19% of 2024’s exploration spend went to grassroots (new frontier) projects, versus approx 50% in the mid-1990s. Companies are focusing on safer bets — extending known deposits or brownfield drilling near existing mines — rather than wildcat exploration in unknown terrains.

The upshot: we’re finding less gold than we’re mining.

And, not only are discoveries fewer, they’re also generally smaller. The average size of new gold deposits found in 2020–2024 was approx 4.4 Moz, down from approx 5.5 Moz in 2010–2019. No discovery in the past 10 years ranks among history’s 30 largest gold finds.

Another challenge is the time lag from discovery to production. Even when a new deposit is found, developing a new gold mine takes on average 20.8 years globally or more due to permitting, environmental reviews, and engineering hurdles. This means that even if a major gold discovery is made tomorrow, it might not produce gold until the 2040s.

Why gold explorers and Juniors matter in Majors’ reserve crisis

For the large mining companies that produce most of the world’s gold, the implications of this discovery deficit are stark as reserves at major gold miners steadily erode.

Statistics from McKinsey & Company show, from 2012-2017, the combined reserves of the 20 leading gold companies declined from about 967 million ounces to 713 Moz – a 26% drop in just five years. The average life-of-mine (how long their reserves would last at current production) shortened from 19 years to 16.5 years over that period. It is unlikely this trend changed into the 2020s.

Many top producers are essentially mining faster than they replenish. If they cannot replace what they dig up, they will, as one analysis bluntly put it, “deplete themselves out of business”.

We’ve already noted the decline of South Africa’s Witwatersrand and the lower output from Nevada’s Carlin Trend and Australia’s Super Pit, but large companies like Newmont, Barrick, AngloGoldand Newcrest built their wealth on big, long-lived deposits discovered decades ago. Many of those mines are now past peak production or facing higher costs to maintain output as grades fall.

In short, the gold majors face a reserve crisis: without new mines, their production will inevitably decline over the next 10-20 years.

So, how are the majors responding? Primarily by acquisition and efficiency rather than organic discovery.

Historically, big gold companies have relied on M&A (mergers and acquisitions) to replace reserves, accounting for an estimated 42% of their reserve growth from 1998–2011 — and this pattern continues as the majors, reluctant to risk capital on high-risk exploration, wait for a junior to prove a deposit and then buy the asset or company outright.

Some of the major gold-sector M&A over roughly the past 5 years include:

| Deal | Target / Acquired | Approx Value / Terms | Year / Timing |

| Newmont | Newcrest Mining | US$19.2 bn | 2023 |

| Gold Fields | Osisko Mining | US$1.57 bn | 2024 |

| Royal Gold | Sandstorm Gold & Horizon Copper | US$3.5 bn | 2025 (announced) |

| AngloGold Ashanti | Centamin | US$2.5 bn | 2023 / 2024 |

| Northern Star Resources | De Grey Mining | US$3.2 bn | 2024 |

| Dundee Precious Metals | Adriatic Metals | US$1.25 bn | 2025 |

However, the junior sector has its own challenge: access to capital.

Exploration is expensive and generates no revenue until a mine is developed. During the downturn of 2017-2019, the number of active mining juniors on Canada’s TSX Venture Exchange dropped sharply.

Even with gold at record highs in 2025, juniors still depend on fickle equity markets. After two years of elevated interest rates, risk capital has been slow to return, leaving exploration budgets constrained despite the stronger metal price.

The recent surge in gold price and bullish sentiment has sparked greater investor interest in mining equities.

- in Canada, a top-tier mining country, gold output has actually been rising, up 32% from 2014 to 2024, thanks in part to new mines coming online in provinces like Quebec, Ontario, and Nunavut. This “Gold Rush 2.0” in Canada shows that with supportive policies and active exploration, it is possible to boost production even as older mines decline

- Australia likewise leads in both exploration spending and reserves (it holds the world’s largest gold reserves in the ground at 12,000 tons), leveraging decades of geological know-how in Western Australia’s gold belts

From an investment and policy perspective, the narrative is clear: gold explorers and developers are not just speculative plays – they are strategic assets in a world where large miners are struggling to replace reserves.

The industry is facing a ticking clock: and the early movers will win the race.

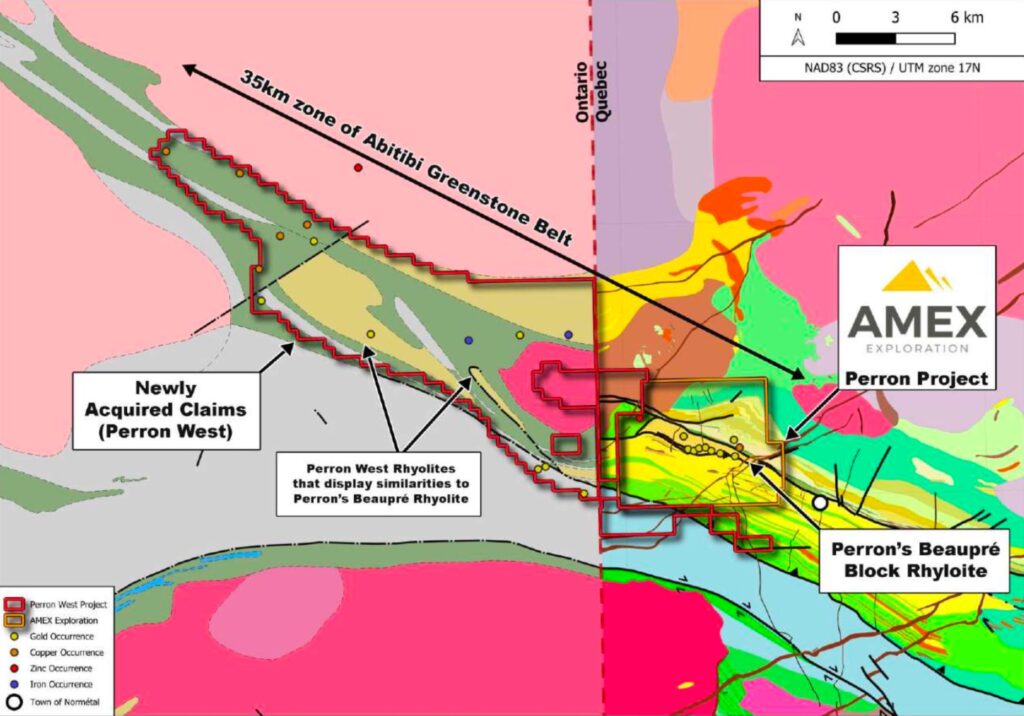

AMEX Exploration Inc. (TSXV: AMX)is strategically positioned to benefit from the gold reserve crisis facing the industry. Its 100%-owned Perron Project in Quebec’s Abitibi Greenstone Belt has already delivered over 500,000 metres of drilling and a 2025 mineral resource estimate of 1.615 Moz at 6.14 g/t Au (M&I) plus 698 koz at 4.31 g/t Au (Inferred), including the ultra-high-grade Champagne Zone with 831 koz at 16.2 g/t Au .

A Preliminary Economic Assessment released in 2025 outlined average annual production of 112,000 oz Au over the first 10 years, with an after-tax IRR of 70% and all-in sustaining costs around US$1,061/oz at US$2,500 gold . With low initial capex, >95% metallurgical recoveries, and year-round access to Quebec’s infrastructure and workforce, Perron is advancing toward development with clear scalability.

Backed by major shareholders including Eldorado Gold (17%) and Eric Sprott (10.5%), Amex is well-funded and continues to expand its high-grade discoveries. In a market where global gold reserves are dwindling , Amex offers direct leverage to one of the few district-scale, high-grade discoveries advancing in a Tier-1 jurisdiction.

Conclusion: a race to replenish global gold reserves

On the current trajectory, known gold reserves could run critically low within the next 20–25 years — a paradigm shift in gold market dynamics. The next few years will be crucial in determining whether the industry can reverse the long-term downtrend in discoveries.

Rising gold prices are creating a window of opportunity: both major and junior miners are now better funded supported by strong cash flows and renewed investor interest, with all eyes now on junior gold explorers and developers, these critical players are poised to shape the future of the gold industry.