Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

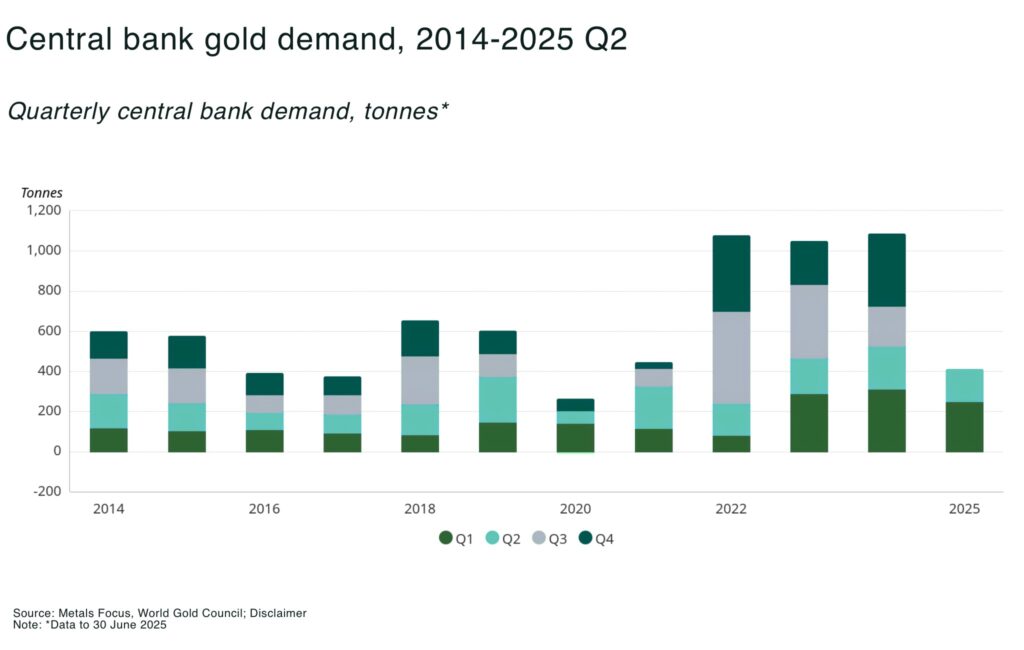

- Historic sovereign gold rush: Central banks bought a record 1,136 tonnes of gold in 2022 – the most in any year since 1967 – and have exceeded 1,000 tonnes annually for three years straight

- Diversification: 95% of central bankers expect global gold reserves to keep rising over the next year, as Yuan falls 20% from 2022

- Emerging markets lead the buying: China’s central bank has added gold for ten consecutive months and Beijing is even offering to store other nations’ bullion in Shanghai vaults

- Market impact – a new price driver: Central banks now hold roughly one-fifth of all the gold ever mined

In 2024, central banks worldwide bought an estimated 1,045 tonnes of gold, following 2022’s record 1,136 tonnes (the highest on record, back to 1950s) and another 1,050t in 2023. It’s a three-year buying binge unseen in modern times.

From Beijing to Warsaw, sovereign buyers are hoarding bullion at levels that far exceed historical norms, eclipsing the annual average of ~473t from 2010–2021.

The result is a historic shift: central banks have become the major gold bulls, reshaping demand patterns in the US$12.5 trillion gold market (about 201,000 tonnes above ground).

This sustained official-sector appetite marks the continuation of a trend: central banks have been net gold buyers 15 years in a row since the 2008 financial crisis, reversing the behavior of the 1990s and 2000s, when many central banks (especially in Western Europe) sold hundreds of tonnes per year.

The breadth of buyers is also striking, suggesting a broader structural shift. For example, in 2024, over 12 central banks increased reserves, including:

- Poland +90t

- China +44t (reported)

- India bought 73t (x4 its 2023 purchases)

- and others like Singapore, Türkiye, Uzbekistan, Egypt, Qatar and Iraq have also added significant volumes in recent years

Poland’s central bank governor openly aims to keep raising gold to 30% of national reserves (Poland reached 515 tons, approx 17% of its reserves, after 2024’s buys).

What’s driving this central bank gold buying spree?

The drivers behind the central bank pivot to gold suggest this is no temporary trend:

- Geopolitical risk: in a world of rising tensions and economic sanctions, gold is seen as a safe haven asset. Unlike foreign currency reserves or bonds, gold “does not rely on any issuer or government” and carries no credit or default risk

- Devaluation: we are no believers in the idea of de-dollarization, but the value of the dollar has fallen to a 5-year low — and we expect it to fall further. This is happening as the dollar’s share of global foreign exchange reserves also gradually falls (down to approx 58–60% from around 70% two decades ago).

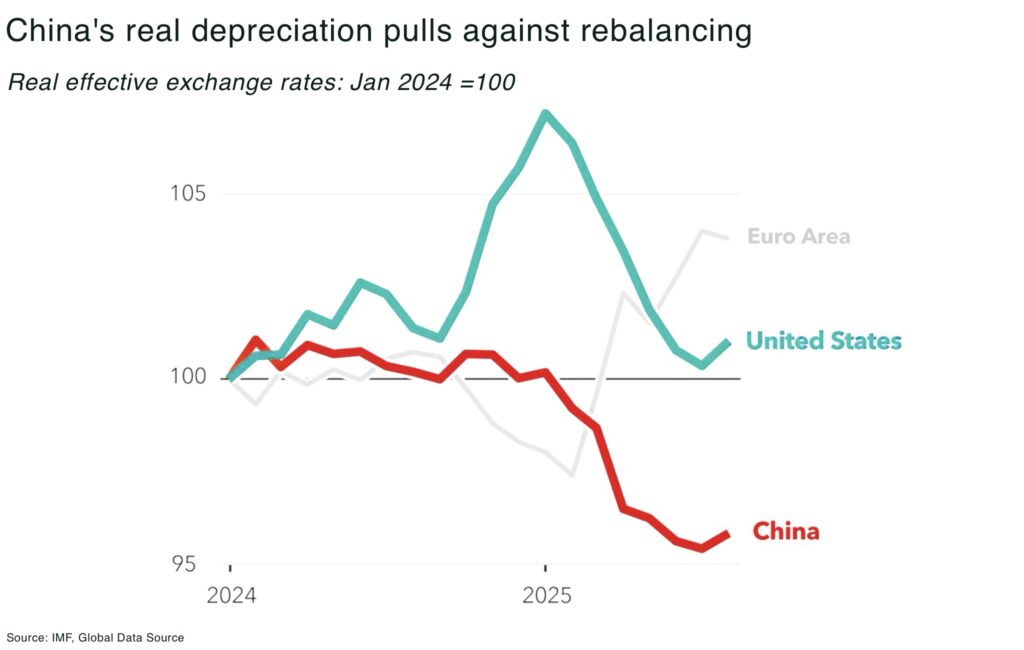

More importantly, beyond many of the dollar headlines, China’s currency depreciation is also supporting a higher gold price. The renminbi’s real effective exchange rate has fallen by nearly 20% since early 2022, increasing the appeal of gold as a store of value and contributing to upward pressure on prices. By eroding confidence in local‑currency savings while raising the domestic cost of imports, a weaker RMB channels demand into bullion — both from households and, indirectly, through reserve management as RMB depreciation amplifies the official bid: as exchange‑rate risk rises, central banks rotate into issuer‑free gold, tightening float and reinforcing the multi‑year ~1,000t annual demand backstop - Inflation, interest rates and (stealth) quantitative easing: gold historically performs well in times of inflation and currency debasement, so central banks have looked to it as an inflation hedge and store of value — and interest rates have been steadily increasing (again)

- Volatility hedging is crucial for central banks facing unpredictable global markets, with a mandate for safety and liquidity

Central Bank Survey Highlights (World Gold Council Survey)

- 95% of central bankers expect global official gold reserves to increase further over the next 12 months. None of the surveyed banks plan to reduce their own gold holdings in that period

- 76% of central banks believe gold will make up a higher share of their reserves five years from now (vs. today), while a similar 73% foresee a smaller role for the US dollar

China’s move as a major buyer of bullion

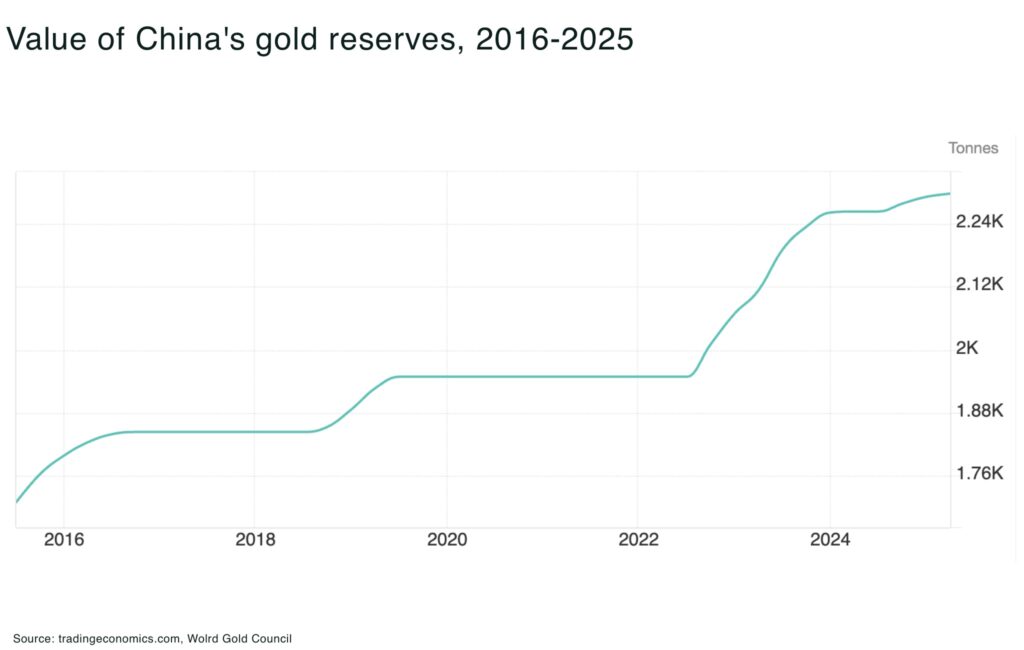

No country embodies this trend quite like China. It officially (we suspect the real figures are significantly higher) added 225 tonnes from late 2022-2023, with its reported reserves to 2,280 tonnes as of end-2024. Beijing has since bought gold for ten consecutive months up to the present.

Even so, gold still accounts for only ~5% of China’s massive US$3+ trillion reserve portfolio, leaving room for further accumulation.

Now, China is leveraging gold to extend its financial influence, with reports the People’s Bank of China is offering to store foreign central banks’ newly purchased bullion.

We are (very) uncertain how many countries would trust shipping and storing their gold in vaults in Shanghai, but at least one Southeast Asian central bank is reportedly interested. The goal for Beijing: establish itself as an alternative bullion safe haven and erode the dominance of Western vaults in London and New York.

The move highlights the trend to bring gold home. The Bank of England remains the top gold custodian with 400,000 bars of gold, mostly foreign reserves, in its London vaults. But, for example, in 2024, India repatriated 100 tonnes of its gold from the Bank of England’s vaults back to domestic soil. Central banks as diverse as Germany, Hungary, Turkey, Venezuela, and the Netherlands have repatriated portions of their holdings over the past decade. According to a 2024 survey, 68% of central banks now keep most of their gold within their own borders, up from roughly 50% in 2020.

The freeze of Russia’s FX assets was a wake-up call that “offshore” reserves carry political risk. Even US allies like Poland have built new high-security vaults to house gold domestically. In this light, China’s offer to host others’ gold on Asian soil is part of a broader attempt to rebalance the global financial safety net.

What are the risks and opportunities for gold miners as Central banks reshape the market

This surge in sovereign gold buying is reverberating through the gold market in multiple ways:

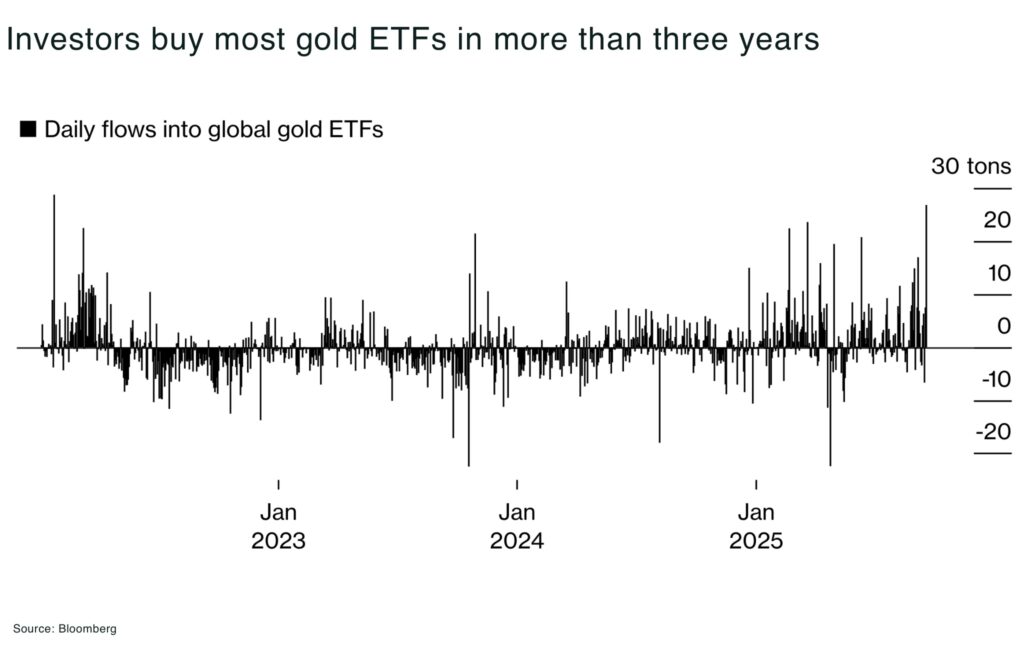

First and foremost, central bank demand has provided a strong price backstop. Even as high interest rates and a strong dollar caused some investors to trim gold positions in 2023, central banks filled the gap. Now, the Federal Reserve is lowering interest rates and exchange-traded funds hit a three-year high — driving gold prices to all-time highs.

For gold miners and explorers, the implication is a more robust demand floor. Annual central bank buying of approx 1,000 tonnes soaks up roughly one-quarter of global mine output each year. It’s as if a buyer of last resort is consistently present, which can reduce downside volatility.

The flipside is that if central banks were to pause purchases (or in a worst case, become net sellers as in the 1990s), it could remove a key pillar of support. However, none of the signals point to an imminent reversal, quite the opposite. As noted, a record share of central banks plan to add gold in the near term. With geopolitical rivalries and inflation concerns persisting, their motivations to hold gold remain compelling.

Another impact is on the liquidity and flows in the market. Central banks often buy gold through off-market transactions, sometimes directly from domestic mine production or via quiet bilateral deals, rather than on the open market. For example, the central banks of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan have long-standing programs to buy gold from their local mines (providing miners a ready buyer while boosting national reserves). This can help reduce the amount of gold hitting international markets, tightening available supply at the margins.

The World Gold Council noted that official reported purchases in 2024 accounted for only 34% of its estimated total official sector demand – the rest may be unreported or delayed in disclosure (like the PBoC unexpectedly announcing 32 tons bought in a month after years of silence) — which, can by itself, can jolt market sentiment.

For companies like AMEX Exploration Inc. (TSXV: AMX), higher gold prices and a central bank “backstop” unlocks critical advantages, improving economics of new discoveries and aggressive drilling for resource expansion.

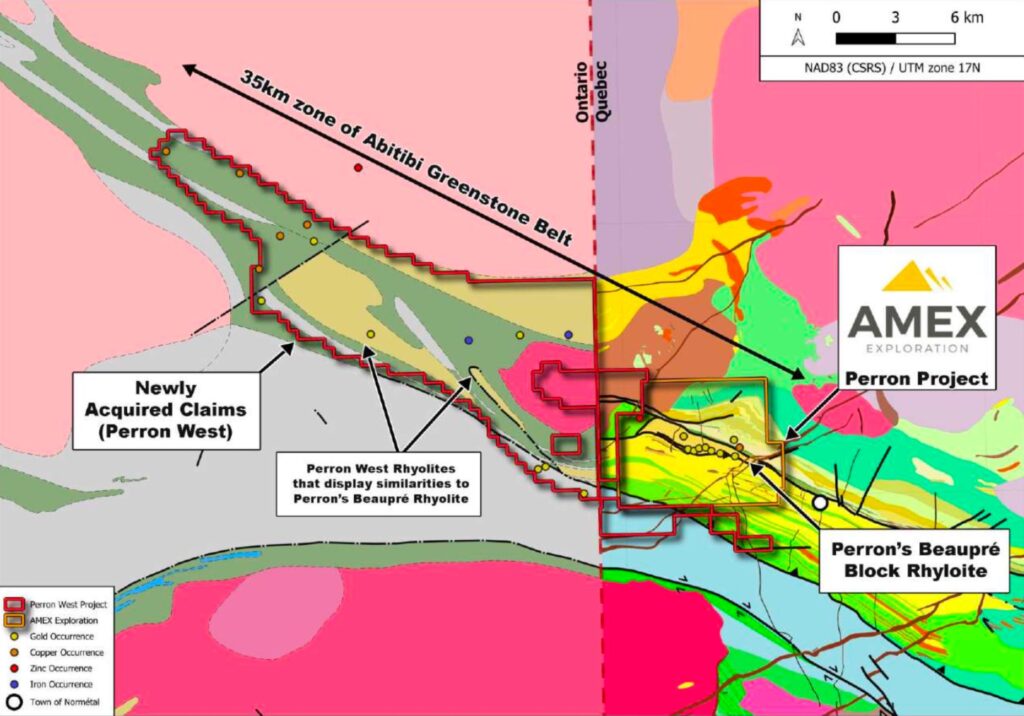

Amex Exploration’s Perron Gold Project in Quebec exemplifies why this matters. With drilling highlights including intercepts of over 100 g/t Au across multiple metres at the Champagne Zone, and more than 500,000 metres of drilling completed to date, Perron is emerging as one of the few large-scale, high-grade discoveries globally.

Central bank buying provides indirect leverage for explorers: it sustains higher baseline gold prices, incentivizes continued investment into exploration, and underscores the importance of high-quality deposits in secure jurisdictions. AMEX Exploration’s disciplined treasury management and strategic positioning reflect these trends, enabling sustained drilling and a near-term path to production without excessive dilution.

And, in Quebec’s Abitibi belt, where infrastructure and production history already support development, this dynamic positions Amex not just as a junior explorer but as part of the supply chain resilience central banks are implicitly underwriting through their bullion hoarding — projects like Perron gain strategic significance as majors, seeking to replenish declining reserves, look for attractive acquisition targets.

Conclusion

The big picture in the record price of gold is about risk management on a national scale: countries are hedging against currency risks, potential sanctions, and a less stable global order by keeping more of their wealth in gold.

Importantly, demand by central banks is anchored in strategic motives rather than short-term speculation. This bodes well for gold’s long-term investment case as economic and geopolitical drivers behind the gold rush continue.

And analysts agree, with Goldman Sachs forecasting that gold prices could soar to $5,000/oz if just a 1% shift of large bond investors’ portfolios moves into gold. The sustained accumulation by central banks – alongside interest from institutions and individuals seeking inflation hedges – could be the spark for such a re-rating of gold’s value.

In conclusion, the central banks gold buying spree is reshaping the global market- putting miners and explorers at the forefront.