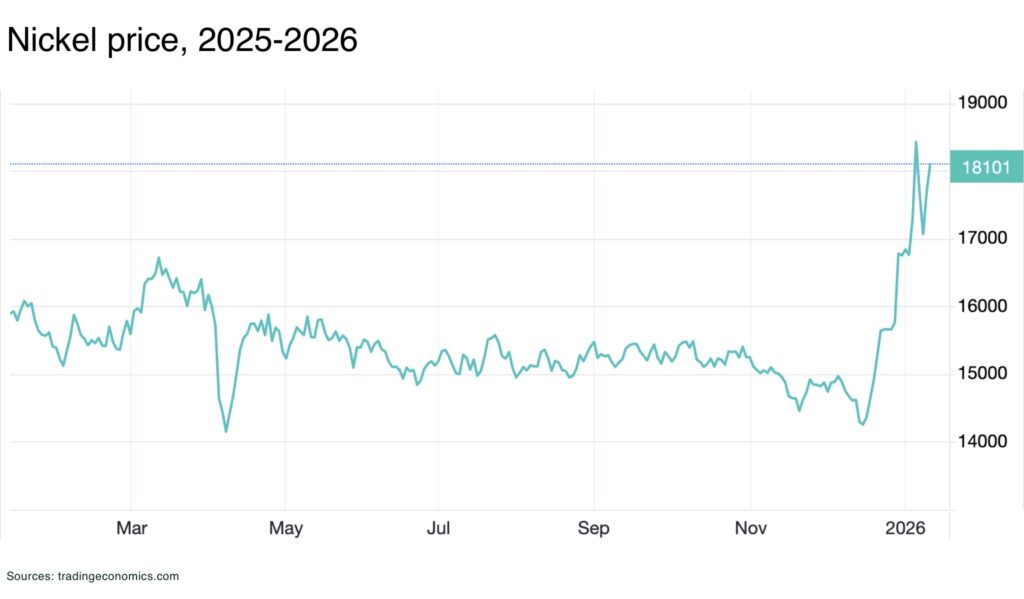

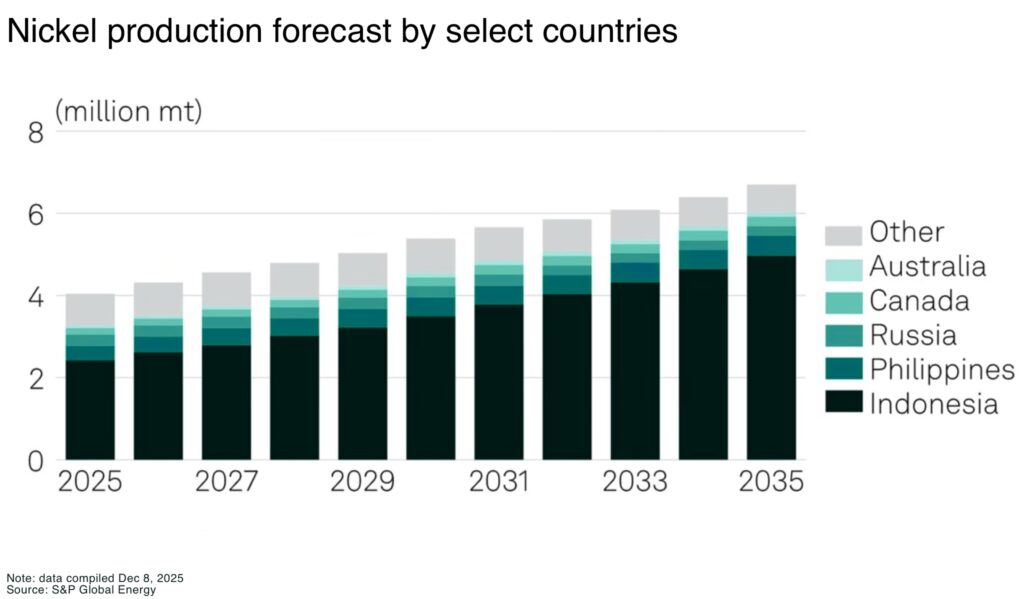

- nickel price rally: nickel prices jumped to $16,500–$18,500per ton range in early January 2026 – hitting their highest levels in over two years

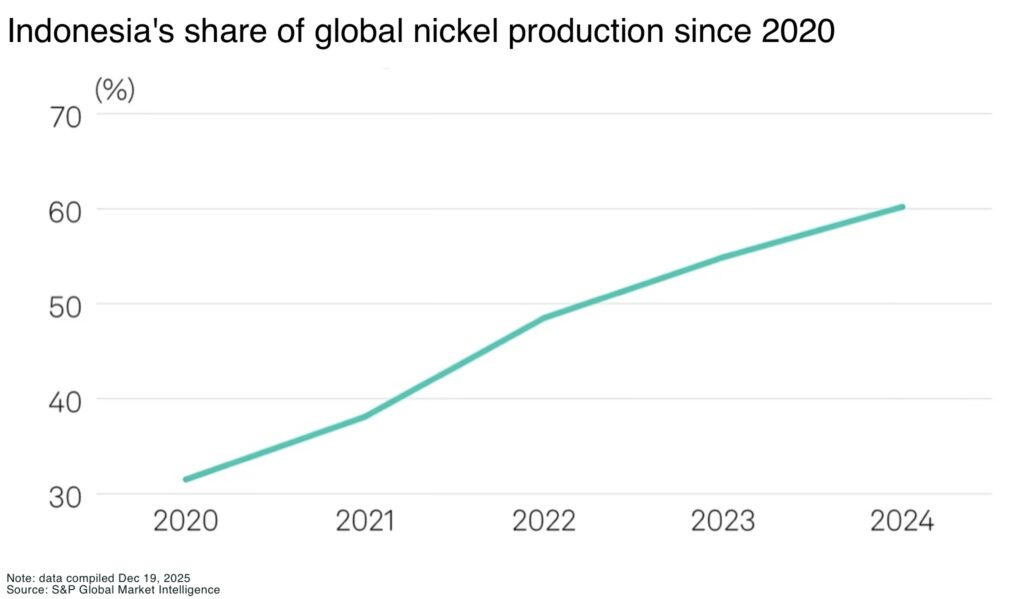

- Indonesia reins in output – begins pivot from maximizing supply to maximizing value: Indonesia, which now produces two-thirds of the world’s nickel, is delaying mining permits and slashing nickel output quotas to support prices

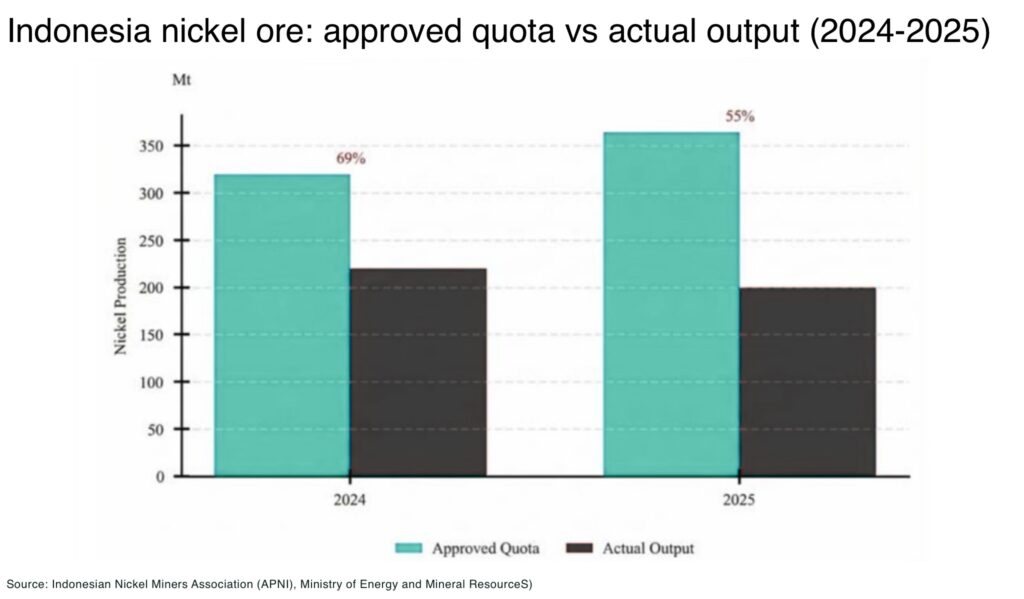

- “Paper surplus” deflated: only about 55% of Indonesia’s approved nickel ore production capacity was actually utilized in 2025 – meaning much of the supposed surplus was a statistical illusion

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

Indonesia’s new nickel supply strategy

Indonesia — the world’s dominant producer with two-thirds of nickel supply — has signaled major supply cuts for 2026, triggering a rally in nickel prices, including:

- revising the annual mining quota revision process from 3 years to one year to manage supply and pricing

- banning new NPI smelters and HPAL processing plants to limit new nickel production and focus future investment on adding value downstream from existing production

- tighter environmental and forestry enforcement with significant fines levied

PT Vale Indonesia has temporarily halted mining operations in early January after failing to secure its 2026 mining quota approval, underscoring the government’s stricter enforcement of annual work plans rather than multi-year permits. The halt has limited direct production impact but serves as a highly visible indicator that regulators are tightening control of output across the sector.

The latest policy moves are being interpreted by markets as a structural shift from a previously oversupplied market regime towards active supply management and price support. Nickel prices soared by more than $4,000 per tonne ($2/lb) in 4 weeks over US$18,000 per tonne — the highest levels in over two years.

Over the last decade, Indonesia’s policy has been one of massive expansion across nickel mining and processing to dominate global market share:

- incentivising both upstream and downstream investment — from mine to refined product

- flooding the market and reducing prices to take out global competitors

In 2020, the government in Indonesia banned raw nickel ore exports but allowed the export of refined nickel products to boost investment in processing plants — by forcing companies to process and manufacture in the country — and the plan worked. By July 2023, there were 43 nickel smelting facilities in operation in the country, 28 under construction, and 24 more being planned in the country.

Indonesia increased its market share from 31.5% in 2020, to 60% in 2024, and forecast to reach more than 75% by 2030.

The result of what we’ve called “The Great Nickel Trade War” has been closure of nickel mines across the West, in particular, at least 8 closures in Australia and New Caledonia in 2024 — driving Indonesia’s share of global nickel production even higher.

Now, the scramble for market share has given way to supply discipline, with Indonesia moving to defend prices and consolidate its monopoly power as a one country “ONEC” where it now controls more of the nickel market than OPEC did at its peak in the early 1970s

Where’s the nickel surplus

Key to Indonesia policy shift is the mining quota system, known as the RKAB (annual work plan and budget). All miners must submit an RKAB production plan each year for government approval, which sets an output quota.

In 2023, Indonesia relaxed the RKAB system to issue three-year quotas in one go, but this backfired as companies secured excessive allocations far above their near-term capacity to use the extra quotas if prices increased.

For example, Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources approved production quotas (RKAB) totalling 364 million tons for 2025. However, according to the Secretary General of the Indonesian Nickel Miners Association, actual production through September 2025 reached only approximately 200 million tons — a utilization rate of only 55%, according to a recent ICBC report.

“The fundamental driver of the perceived nickel glut is the massive disconnect … between approved production capacity and actual production,” noted analysts at ICBC in a December report, Nickel Market Poised for Strong Recovery from Mid-Term Trough

In other words, hundreds of millions of tons of nickel ore existed only on paper.

In an effort to manage this “phantom surplus,” Jakarta announced in October 2025 that it had shortened mining quota validity to one year effective immediately. Quotas already granted for 2026 and 2027 were voided. The move came after the government suspended 190 coal and mineral mining permits after they failed to meet their obligations for the rehabilitation of mine-damaged land or comply with production quotas.

“We are slashing production under the RKAB,” Energy and Mineral Resources Minister Bahlil Lahadalia said in December 2025, to ensure prices are “rational.”

Indonesia’s pivot from disruptor to price guardian

For nickel investors, Indonesia’s policy pivot marks a new era. The world’s top nickel producer is no longer acting as a growth-at-all-costs disruptor, but instead more like an OPEC for nickel “ONEC”, ready to adjust the taps to defend a price level.

The incentives are aligned: for example, in April 2025 Indonesia updated its royalty regime to an ad-valorem system that increases taxes on nickel sales when prices rise, up to 19% at higher price tiers. Under this scheme, every $1,000/ton increase in nickel price boosts Indonesia’s tax revenue by roughly $250/ton, nearly double the sensitivity under the old flat tax .

This gives Jakarta a direct fiscal motive to keep nickel prices higher.

What’s changed — why Indonesia is acting now

Indonesia’s pivot from volume growth to supply discipline reflects a structural shift in how nickel demand, pricing power, and state revenues now align.

Electric battery demand is steady, but slowing

Nickel is a critical component in electric batteries, enhancing energy density and overall performance.

EV sales may still rising globally, but the breakneck growth of recent years has slowed and, importantly, has slowed in key regions – especially Europe and the US, but also in China:

- in the US, growth in EV sales slowed significantly in 2024, increasing by just 10% compared to 40% in 2023

- in Europe, EV sales fell or flatlined in 13 of 27 EU countries in 2024, notably in Germany and France, due to subsidy cuts and phase‑outs; in Germany

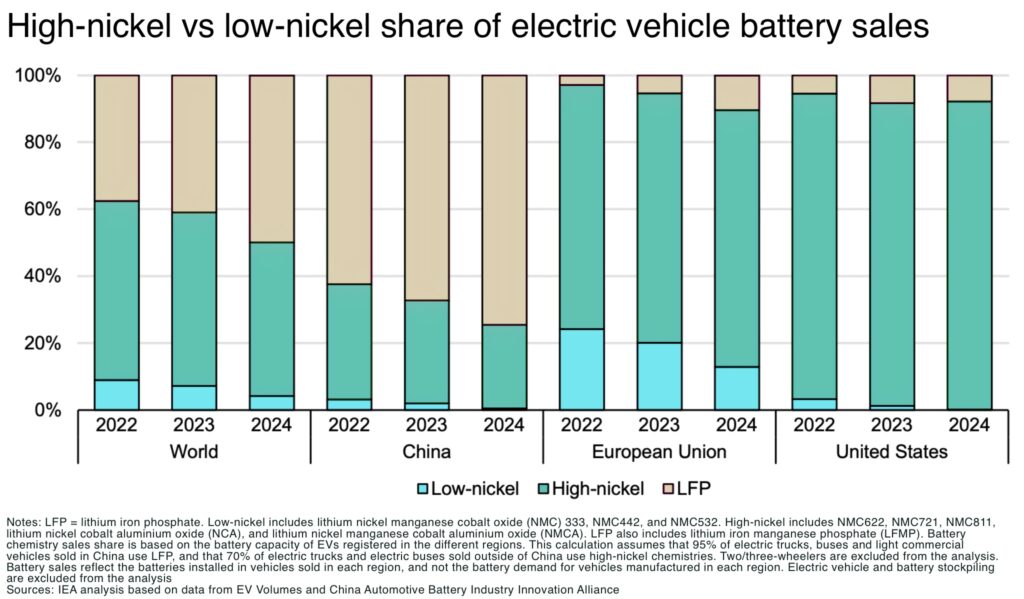

The share of nickel in electric batteries has also been steadily falling as battery manufacturers (especially in China) increasingly switch their battery chemistries from nickel-manganese-cobalt-oxide (NMC) to lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP).

Yes, this slowing demand could be a headwind for nickel prices, but EV demand is still forecast for strong growth over the next decade despite the recent narrative shift — and any major impact on prices would need an absence of supply discipline from Indonesia, which as recent moves suggest, is unlikely.

The shift in investment into electric vehicles and green technologies comes after Indonesia has already achieved its strategic goal of forcing onshore processing. With NPI, HPAL, and battery-material capacity largely in place, the government’s emphasis has shifted from attracting capital to maximizing returns on sunk investment.

Diminishing ore grade

Indonesia controls up to 70% of global nickel supply. This concentration changes incentives as flooding the market no longer buys significant market share. Instead, Jakarta is pivoting to from scaling market share to controlling leverage.

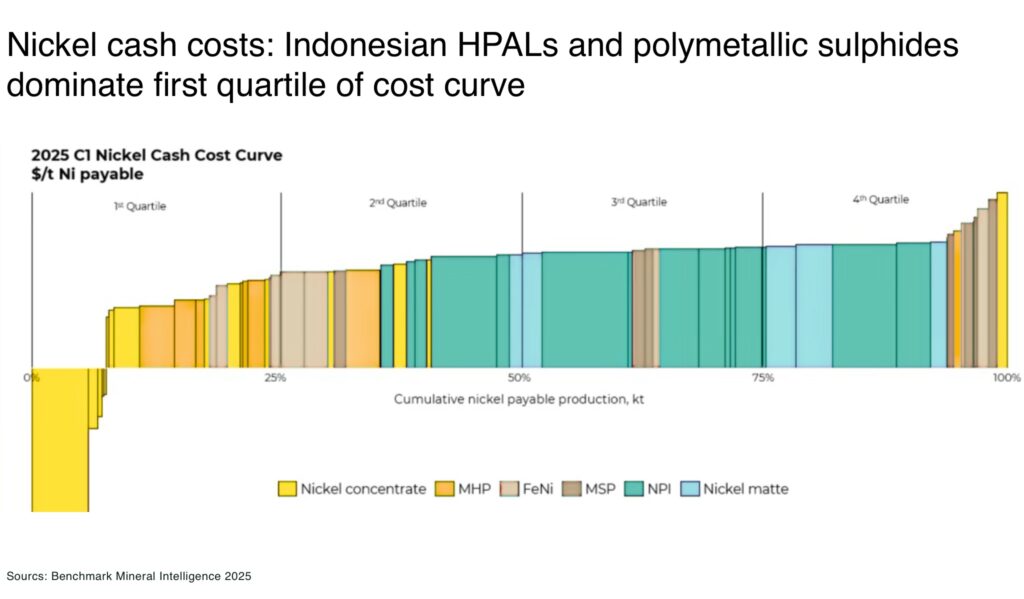

One of the reasons for Indonesia’s pivot is official concern, as well as corporate warnings, over falling ore grades in the country after such dramatic increase in mining.

“The amount of ore Indonesia is mining, is crazy. Back in 2005, it was maybe 6-7 million tons a year, but today, we’re talking 200 million tons a year. So, naturally, ore grades are falling. Fifteen years ago, you were looking at an marginal grade of about 2%; five years ago, an marginal grade of 1.8%; a couple of years back, 1.6%; and now the marginal grade is as down to 1.4% and continuing to trend lower.

That grade compression is precisely why large-scale, long-life sulphide projects outside Indonesia are becoming strategically important again. Canada Nickel sits at the intersection of that shift. Its Crawford project in Ontario hosts one of the largest nickel sulphide resources globally.

As Indonesian marginal supply moves steadily down the grade curve and costs rise, high-tonnage, low-carbon sulphide assets in Tier-1 jurisdictions move from optional to essential, not just for price security, but for automakers and governments seeking secure, non-Chinese controlled, nickel supply chains.”

— Mark Selby, CEO of Canada Nickel, TSXV: CNC OTCQX: CNIKF

The prolonged low-price environment created by Indonesia and China had a clear consequence: new nickel sulphide supply projects effectively stalled. With nickel prices so low, financing scarce, and cost curves rising, only a handful of sulphide projects were able to advance meaningfully. The short list is well known:

- Lifezone Metals at Kabanga in Tanzania

- Centaurus Metals in Brazil

- FPX Nickel in Canada

- as well as Canada Nickel, which is differentiated by scale and scope: the Crawford project has been formally designated under Canada’s Major Projects Office, and described by Prime Minister Mark Carney as a project that “will anchor Canada’s global leadership in clean industrial materials”. The company has published seven additional NI 43-101 compliant nickel resources within the Timmins Nickel District. And that record reflects execution through a weak price cycle, rather than reliance on a higher-price assumption

Indonesia’s budget deficit widens, trade and current account deficits re-emerge

Indonesia’s budget deficit has widened, as the government increases spending to support economic growth amid global headwinds. One of out of eight dollars of Indonesian exports contain nickel and as nickel prices fell from 2022 through 2025 cancelling the effects of further nickel supply growth, Indonesia returned to its historical trade and current account deficits.

The increased spending comes as Indonesia’s 2025 royalty reforms shift nickel taxation to a price-linked ad valorem system, directly tying government revenue to higher nickel prices. At prices above approx $18,000/t, state take per tonne rises sharply.

Higher nickel prices translate directly to higher export revenues and provide the government a lever to move back towards a current account surplus

For Jakarta, defending prices is now fiscally rational, not politically risky.

How high can nickel prices go?

Nickel’s price response to Indonesia’s — the “OPEC of nickel” — interventions was immediate. By January 2026, the price of nickel was hitting 15-month highs, more than $18,500/ton.

The Secretary General of APNI (Indonesian Nickel Miners Association), General Meidy Katrin Lengkey, has suggested prices may move as high as US$19,000/t.

So what’s next?

We don’t make projections often but there’s every possibility nickel prices could test US$25,000 per tonne under a tightening scenario in the next few years, but — for now — the more defensible clearing range is US$20,000–$22,000/t.

S&P Global Energy CERA forecasts that Indonesia’s production cut could tip the nickel market from surplus toward deficit later this decade

The cost curve has shifted higher as Indonesian ore grades decline, and HPAL projects face rising capex and operating costs driven by higher sulphur costs. And, above US$20,000, and some Australian nickel operations become financially viable again.

Risks

A potential rally — driven by anticipated Indonesian supply cuts — isn’t without risk.

Analysts warn that pressure from industry stakeholders to reverse or soften quota reductions could undercut the price rally; if Indonesian regulators backpedal on output limits, the tightening narrative may weaken and prices could retrace.

“There will be a lot of pressure on them to relent. There are a lot of projects coming onstream this year,” said Macquarie analyst Jim Lennon.

Conclusion

The nickel market is repricing not just supply cuts, but the realization that much of the surplus never existed. That adjustment could prove uneven through 2026, with the risk of overshoot as “paper” capacity is re-adjusted and physical balances tighten.

In the long-term, Indonesia has consolidated control of nickel supply supply during the 2024 trade war, and is now using that leverage to defend value. The shift is deliberate: from volume maximization to price discipline.

Despite the risks, Indonesia is working to put a floor under nickel prices, which means the only direction of travel for prices is up.

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.