The global trade war, driven by tariffs and export controls, poses a significant threat to Western titanium supply chains, intensifying volatility in a market vital for aerospace, defence, clean energy, and everyday products like paint and sunscreen.

The trade war is acting as a catalyst on long-term drivers, from tightening supply to rising demand — and China’s dominance across the titanium value chain, where it controls:

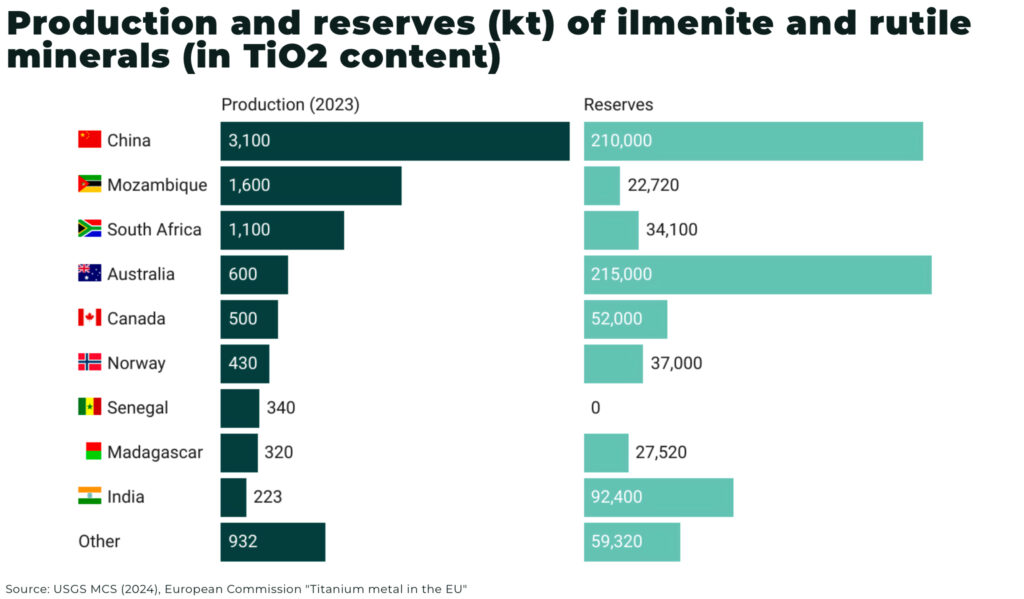

- 34%, the highest global producer, of primary titanium minerals, ilmenite and rutile

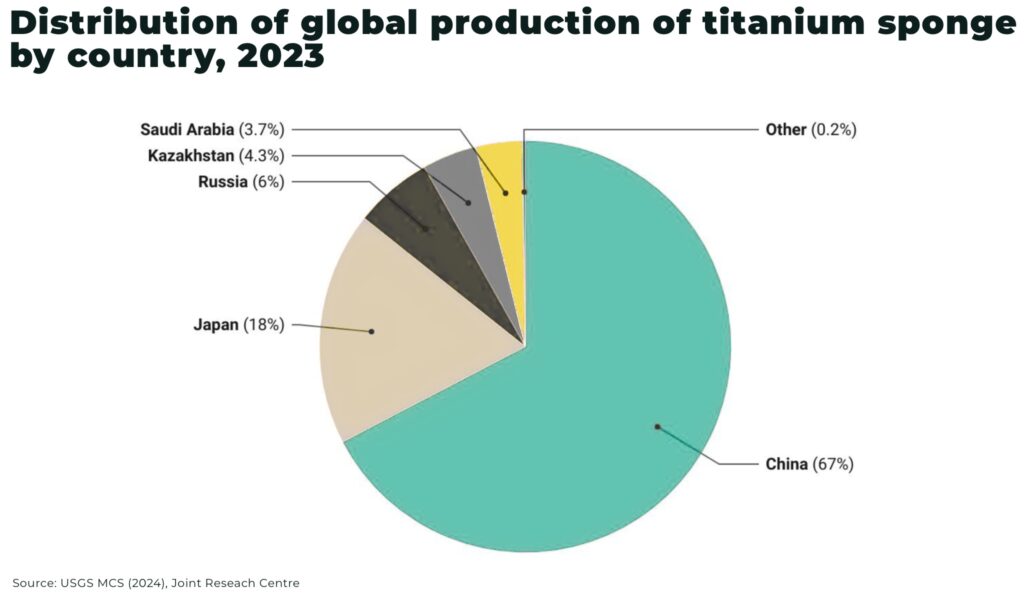

- and 67% of global titanium sponge production

But in the volatility there is also opportunity for junior miners.

Why titanium matters — and why it’s suddenly geopolitical

Governments across the West, including Australia, the EU, and the USA, recognize titanium as a critical mineral due to its importance in two distinct markets:

- pigment-grade titanium dioxide (TiO₂): the world’s premium opacifier, more than 90% of global TiO₂ accounts for the manufacture of pigments for coatings, plastics, and paper

- metal-grade titanium: due to its uniquely high strength-to-weight ratio and high corrosion resistance, titanium metal is essential in aerospace, military applications, medical implants, and high-performance industrial systems

In Q1 2025, according to the US Geological Survey, the US was heavily dependent on imports of titanium mineral concentrates and titanium sponge. For example, the US imported 245,000 metric tons of titanium mineral concentrates (including ilmenite, rutile, and synthetic rutile), while domestic production data was withheld due to confidentiality concerns and limited industry reporting; and the US imported 10,500 metric tons of titanium sponge, with domestic production, consumption, shipments, and stocks of sponge withheld to avoid disclosing company proprietary data. This means that nearly all of the titanium mineral concentrates used in the US are sourced from other countries.

There is only one titanium sponge producer in the US, a facility in Utah with an estimated production capacity of 500 tons per year, although actual production data is withheld to avoid disclosing company proprietary data.

The Titanium Sponge Working Group (TSWG), established under the Trump administration in 2020, found US dependency on imported titanium sponge had risen dramatically from 68% in 2020 to 100% in 2023.

Since then, the US Department of Defense (DoD) initiated funding to develop a fully-integrated domestic mineral-to-metal titanium supply chain, including efforts to restart domestic sponge production, including:

- IperionX: received a $47.1 million to develop a fully-integrated U.S. mineral-to-metal titanium supply chain

- Universal Achemetal Titanium: awarded US$11.3 million contract from the DoD in 2024 for titanium metal research and development, in particular, the development of its novel process for extracting and refining titanium from various raw ores using less energy

- Norsk Titanium: qualified a component for a US DoD application in 2024 using additive manufacturing, demonstrating the potential of new technologies in defense manufacturing

The reason is not just rising demand, but security of supply, aka China.

China’s titanium dominance

China dominates large swathes of the global titanium value-chain, including:

- 34% of the world’s primary titanium minerals (ilmenite and rutile) production originates from China, dwarfing Mozambique (17.5%) and South Africa

- China produces 67% of global titanium sponge supply, having tripled its capacity since 2018

- China’s TiO₂ production capacity reportedly reached 6.05 million tons by the end of 2024, with an additional 1.3 million tons planned for 2025, representing over 55% of global capacity

The core problem for the West is not resource availability, but processing capacity. The real chokepoint is metal-grade production, especially aerospace-certified sponge and titanium alloys. These require highly controlled refining and long-term qualification processes, which only a handful of facilities outside China and Russia currently meet.

This dominance gives Beijing considerable leverage as geopolitical tensions rise, and the risk of China weaponizing this position — through export curbs, licensing restrictions, or retaliatory tariffs — is already being tested in other critical mineral supply chains, as well as a possible US response.

Rare earths, gallium and copper warnings — could titanium be next

Much like rare earths, plenty of titanium-bearing minerals exist outside China — from Australia to Mozambique and Canada. But producing aerospace-grade titanium metal from these minerals is where the bottleneck lies. The certification process for defense and aviation applications is complex, expensive, and time-consuming. Once certified, maintaining that qualification adds another barrier to scaling production.

China

Since 2023, Beijing has implemented export controls on at least 16 different minerals and related products, including gallium, germanium, graphite, tungsten, tellurium, bismuth, molybdenum, and indium.

USA

In an attempt to secure its own supply chain, the US has announced a series of tariffs and investigations into critical mineral supply chains, including:

- Trump signed an executive order launching an investigation into “all US critical minerals imports” — including titanium — that are found to threaten to impair national security

- a 50% tariff on copper set to take effect August 1, 2025, under Section 232 authority, targeting copper imports to boost US production for EVs, military, grid & consumer goods

- as well as tariffs across major commodities such as steel and aluminum

The U.S. is beginning to address the downstream bottleneck. The Department of Defense is now funding projects to restart domestic sponge production and reduce dependency:

- IperionX was awarded $47.1 million to develop a fully integrated mineral-to-metal titanium supply chain and secured their first US Army Task Order under US$99 million SBIR Phase III contract

- Universal Achemetal Titanium received $11.3 million in 2024 to develop a novel, low-energy process to refine titanium from raw ores

- Norsk Titanium qualified a titanium aerospace component for a U.S. DoD program using additive manufacturing in 2024

But none of these investments in the US offer a quick fix.

Instead, the tit-for-tat of export/import controls provides a clear roadmap for other potential — and sudden — critical minerals, for example, titanium, restrictions.

And countries like Russia are also paying attention with reports that in late 2024 Putin considered export restrictions on titanium sponge.

Geopolitical Sanctions and Supply Rerouting

Beyond tariffs, geopolitical events, particularly the war in Ukraine, have already significantly impacted titanium supply chains:

- Ukrainian supply disruption: Ukraine’s titanium sponge exports dropped to zero after the invasion with the ZTMK (Zaporizhzhia Titanium-Magnesium Plant), Ukraine’s sponge plant, out of operation since Russia’s invasion due to its proximity to the front line, with no clear signs of reopening.

- Russia export reductions: While Western sanctions have not directly targeted titanium exports from Russia, some major companies like Boeing and Airbus have voluntarily limited or stopped their reliance on Russian titanium

- supply chain delays: the shift from Russian titanium suppliers has resulted in lead times up to x5 longer than pre-2020 levels, particular on the aerospace industry’s supply chain and titanium

Geopolitical risks are further aggravated by the expected rise in demand from the aerospace and defense industry and the few producers worldwide.

Surging Demand and Tightening Global Supply

Several secular trends are colliding to turbocharge demand for titanium:

- aerospace: global passenger traffic is forecast to exceed 10 billion in 2025, driving new aircraft orders and downstream titanium demand

- defense: Global defense spending hit US$2.46 trillion in 2024, with further increases expected as countries rearm in response to geopolitical instability

- clean tech: innovations like next-generation photovoltaic solar panels and lightweight EV parts are rapidly expanding titanium’s applications

- medical, automotive, consumer: Titanium’s corrosion resistance and strength-to-weight ratio make it increasingly popular for medical implants, automotive parts, and high-end consumer goods

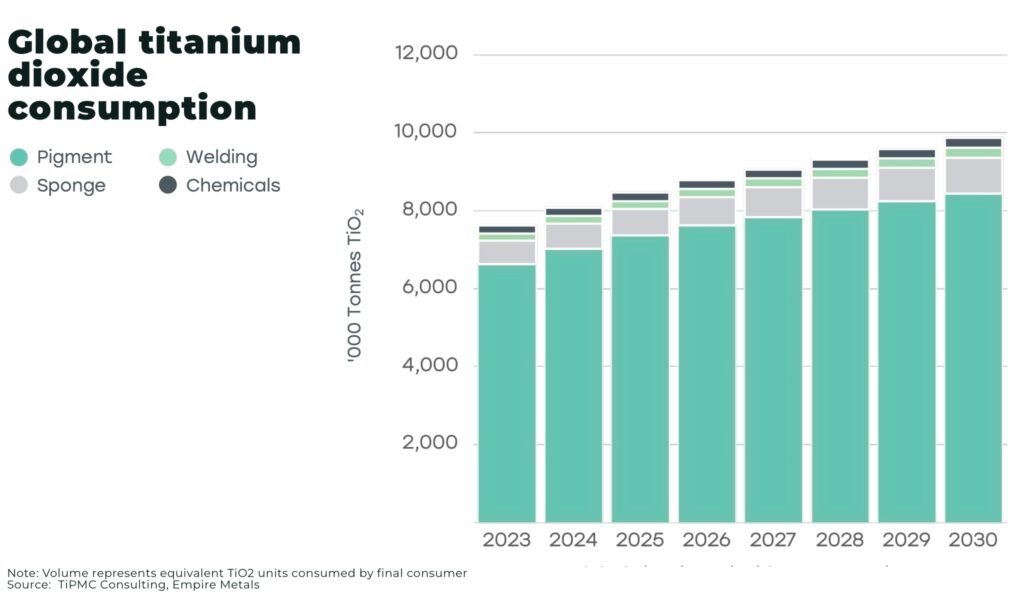

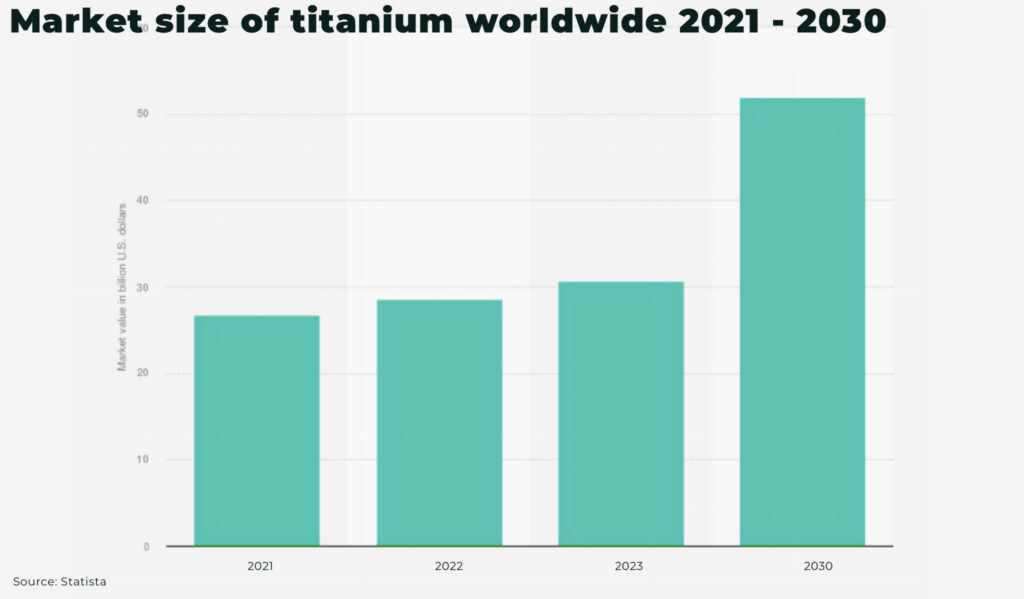

From everyday pigments to jet engines, the titanium dioxide (TiO₂) market was valued at US$24 billion in 2024, with a projected CAGR of 3.7% from 2023-2030.

Yet, while demand soars, supply is tightening:

- premium feedstocks — high-grade rutile and chloride ilmenite — are increasingly scarce outside China, raising costs for Western pigment and metal producers

- certifying new titanium suppliers is a painstaking, multi-year process for high-spec applications like aerospace — there is no “quick fix” to turn on new supply

“Titanium is no longer just a commodity—it’s a strategic asset. As global supply chains reel from geopolitical shocks, and the West seeks to decouple from Chinese and Russian dominance, the need for new, independent sources of high-grade titanium has never been more urgent.

At Empire Metals, we’re not just developing another mineral sands project. Pitfield is a fundamentally different titanium system—district-scale, high-grade, and with a unique anatase/rutile and titanite mineralogy that allows for the production of high-purity TiO₂ with minimal deleterious contaminants. Early testwork confirms its potential to feed both pigment and metal markets at high value.

What sets us apart is not only the scale and quality of our world-class deposit, but also its location in Western Australia — a stable, Tier 1 mining jurisdiction with access to established infrastructure and with strong government support for developing a critical minerals project. This allows us to offer a secure, low-impact, low-cost supply option at a time when the titanium supply chain is under maximum stress.

Pitfield represents a new way of producing titanium — more sustainable, more scalable, and ultimately, more strategic. We believe it has the potential to become a cornerstone in re-shoring the West’s titanium value chain.”

— Shaun Bunn, Managing Director, Empire Metals (LON: EEE OTCQB: EPMLF)

Conclusion

Even with no direct tariffs or export controls on titanium, trade volatility is already acting as a accelerant on underlying fundamental supply-demand dynamics in global titanium supply chains.

Especially in the immediate term, rather than resolving pre-existing issues, these measures have intensified the squeeze on a metal that is already stretched thin by surging demand and a concentrated supply chain.

Efforts to re-shore titanium supply — from sponge to finished metal — remain in early stages, with no quick fix. In the meantime, titanium remains a high-cost chokepoint with little margin for disruption.

This is why junior producers like Empire Metals matter. They offer not just new tonnes, but a fundamentally new model: lower-impact, higher-purity titanium sources in safe jurisdictions, with the potential to serve both pigment and metal markets. For investors, that’s not just a hedge, it’s a strategic entry point into one of the most under-appreciated critical mineral stories.