Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

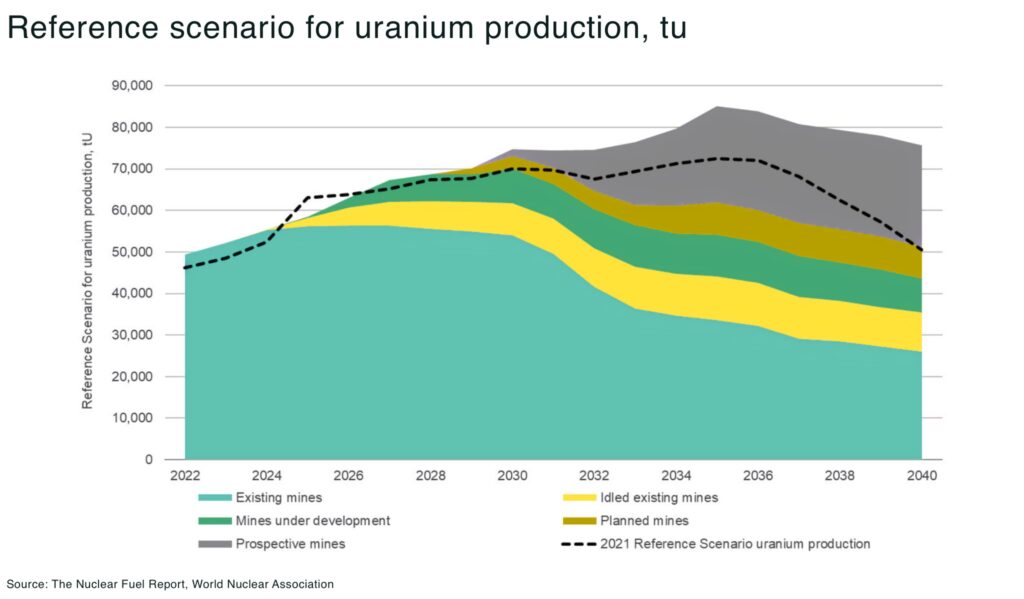

Global uranium demand for nuclear reactors is expected to climb from 68,000 tonnes in 2025 to:

- 86,000 tonnes by 2030

- 150,000-204,000 tU by 2040

To fill the projected gap from 68,000 to 150,000 tU would need the equivalent of approximately 10 new mega-mines producing at Cameco’s recent full capacity by 2040.

But, output from today’s mines is expected to halve in the same period, according to the latest forecast from the World Nuclear Association.

This is obviously unsustainable as hundreds of billions of dollars flow into the largest global nuclear build-out in decades, and sets the stage for a significant rotation into the nuclear fuel sector to match the scale of new reactor commitments.

And yet we are between a rock and a hard place, with government positions around the world succinctly summed up by Carl Coe, the Energy Department’s chief of staff, announcing the US government plans to buy and own as many as 10 new, large nuclear reactors that could be paid for using Japan’s $550 billion funding pledge:

“This is a national emergency”

So, the nuclear reactors are coming — where is the uranium coming from?

Why demand is rising

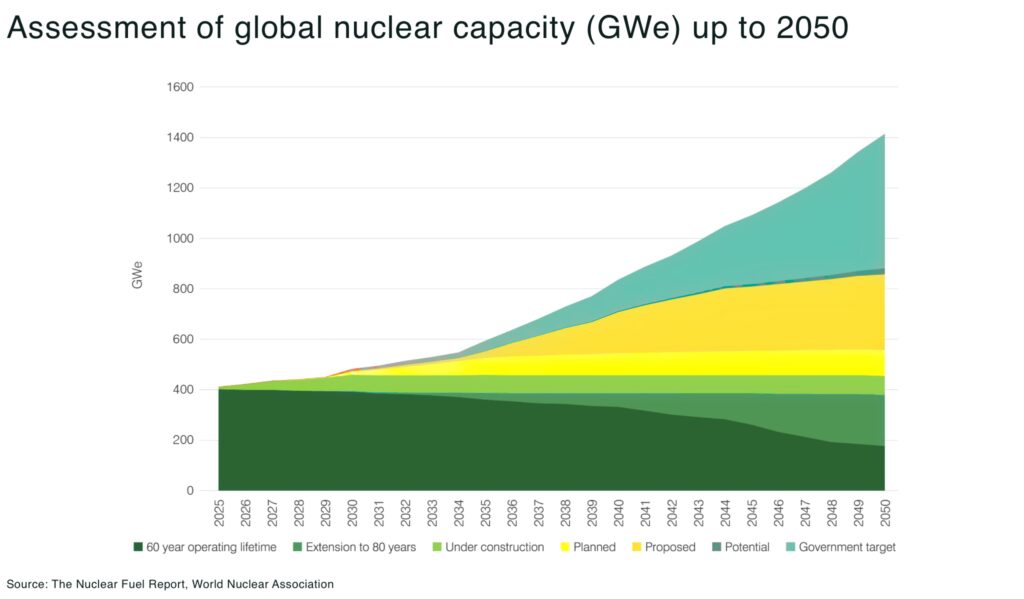

Global nuclear capacity could reach 1428 GWe by 2050, more than tripling existing capacity according to the World Nuclear Association.

This historical re-build-out of nuclear energy is being driven by new electricity demand from data centers, electrification of the energy sector and vehicles, economic development, commitments to reduce greenhouse gases, and concerns over security of supply of fossil fuels.

| Category | Capacity (GWe) | Notes |

| Existing reactors | 383 | 176 GWe (under 60 years operation) + 207 GWe (60-80 years operation) |

| Under construction | 74 | Expected online by 2035 |

| Planned | 99 | Expected online 2030-2040 |

| Proposed | 291 | Expected online 2040-2050 |

| Potential | 30 | Expected online 2040-2050 |

| Government targets | 552 | Additional capacity required beyond projects above to meet national nuclear capacity goals |

| Total (2050) | 1428 GWe |

So far, 31 countries have signed the Declaration to Triple Nuclear Energy, which supports a global goal of tripling nuclear energy capacity by 2050, compared to 2020. This would mean global nuclear capacity would have to expand to at least 1200 GWe by 2050.

And investment is ramping up across the industry, including, in 2025:

- US$80 billion deal between US govt and Westinghouse Electric to build out new nuclear reactors across America

- US$27.44 billion approved by China’s State Council for construction of 10 new nuclear generating units

- Japan is set to restart the world’s largest nuclear reactor, the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant

- the Czech Republic plans a US$19 billion nuclear expansion to double output

- UK govt confirmed more than US$18 billion to build Sizewell C

Long-term uranium contracting is already sharply up as utilities hedge against future supply shocks; eg Cameco Corporation reports approx 119 million pounds of uranium were placed under long‑term contracts by utilities in 2024.

And utilities typically lock in long-term uranium supply several years in advance before a new reactor comes online. Most trade is via 3-15 year term contracts with producers selling directly to utilities at a higher price than the spot market, reflecting security of supply.

And, with more reactors online, the uranium feed-stock requirement rises accordingly. The challenge is that supply is expected to tighten.

“The scale and speed of new supply the world needs is unprecedented. If nuclear is going to triple, the fuel sector has to move just as fast — and that means large, high-grade discoveries in proven jurisdictions. This is exactly why we’re advancing F3’s portfolio in the Athabasca Basin: projects that can scale quickly will define the next decade.”

— Dev Randhawa, Chairman and CEO of F3 Uranium Corp (TSXV: FUU, OTCQB: FUUFF)

Why uranium supply will struggle

Global uranium supply is already running 10-20% below reactor demand driven by a structural supply deficit and growing global policy support. Now, the World Nuclear Association and other analysis warn that output from existing mines is expected tofall 50% between 2030 and 2040 as deposits deplete.

“As existing mines face a depletion of resources in the next decade, the need for new primary uranium supply becomes even more pressing… Considerable exploration, innovative mining techniques, efficient permitting and timely investment will be required” — World Nuclear Fuel Report: Global Scenarios for Demand and Supply Availability 2025-2040, World Nuclear Association

In particular, the world’s two largest uranium producers — Kazatomprom and Cameco — have in recently announced uranium production cuts.

Governments will need to invest in accelerated permitting, mining innovations, and new exploration for uranium but, as the World Nuclear Association’s flagship fuel report warns, the expected timeline to develop new mines is “getting longer, not shorter” from 8-15 years to 10-20 years. This means, for any new mine brought online by 2030, won’t contribute meaningfully until 2040-2050 — precisely when the gap widens most.

And it’s not just mining, but uranium enrichment. Russia has the world’s largest enrichment capacity, but imports are currently sanctioned by the US. Deals to expand the development of HALEU projects in the West are in the pipeline, but it will take years/decades to reach capacity at scale.

US tarrifs have also impacted security of supply, including:

- Russia: ban on unirradiated, low-enriched uranium (LEU) imports, with waiver options and quotas, and threat of 500% tariff on countries that import Russian uranium

- Canada: 10% tariff on uranium imports

- Mexico: 25% tariff on all imports, including uranium

- China: 55% tariff on imports, potentially including uranium; as well as a probe to stop China circumventing the Russian ban

- Kazakhstan: representing 43% of global uranium production, is at risk of secondary sanctions via China or Russia

Meanwhile, secondary supplies (stockpiles, military-downblend uranium, tails-re-enrichment) are shrinking in relevance.

The uranium bottleneck

The narrative is shifting from “nuclear is back” to “uranium may be the bottleneck.”

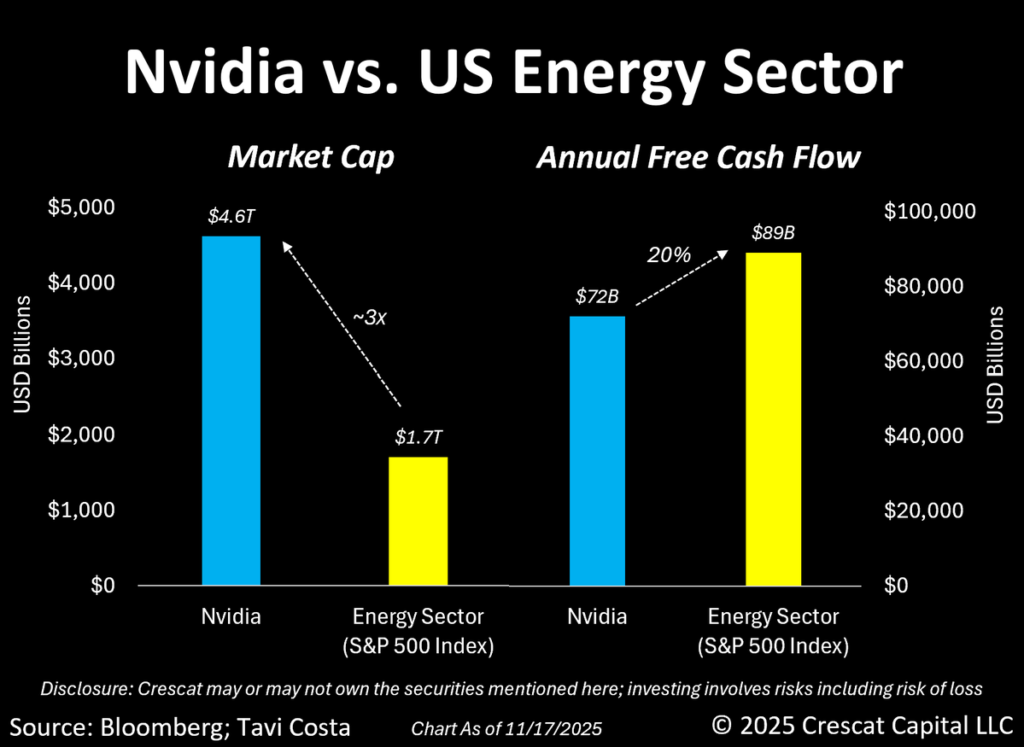

For example, investment has poured into data centers but not, in the same scale, into the energy sector, including uranium mining.

As Otavio (Tavi) Costa, macro investor, highlighted recently:

“Nvidia is now valued at nearly three times the entire energy sector. Almost three times. And no, it doesn’t generate more profit than energy companies in the S&P 500. In fact, the combined free cash flow of this sector over the last year is about 20% higher than Nvidia’s. Tech innovation is incredible — but let’s not forget that something still has to power it.”

The uranium sector is scrambling to scale for the surge in future demand, but the clock is running down — and any further supply disruption could force earlier contracting, strategic reserves, and supply-chain diversification.

For investors, this opens opportunities with upstream explorers and miners with viable projects gaining leverage.

Conclusion

Time is running out to bring new mines and enrichment capacity online fast enough to match reactor restarts and new builds. Any delay in project development risks leaving reactors idle or dependent on fragile supply chains.

Efficiency gains can stretch existing resources, better recovery from ageing deposits, new ISR techniques, marginal grade improvements, or even temporary geopolitical fixes such as reopening access to Russian enrichment. But these measures only extend current supply; they don’t create new supply at the scale the 2030s and 2040s require.

Building the equivalent of ten Cameco-scale mines by 2040 would be a historic undertaking, and only a handful of regions on earth could host assets of that size. As we’ve highlighted before at The Oregon Group, Canada’s Athabasca Basin remains the standout jurisdiction, with the geology, scale, and political stability to support such a scale at world-class production.

Every day of delay increases the risk to the entire nuclear development chain. No utility can afford a reactor that’s built, licensed, and ready — but waiting for uranium.

That urgency explains the size and speed of the moves we’re now seeing in the market, and why momentum is set to accelerate as investment rotates on the realiszation that in nuclear energy, the sequence is non-negotiable: the fuel comes first.

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.