Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

Let’s start with the good news.

The West is extremely concerned over securing critical mineral supply chains, especially after Covid, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and and escalating geopolitical tensions between China and the US.

For example, the US Inflation Reduction Act only allows electric vehicles manufactured with domestically sourced minerals to be viable for significant tax credits.

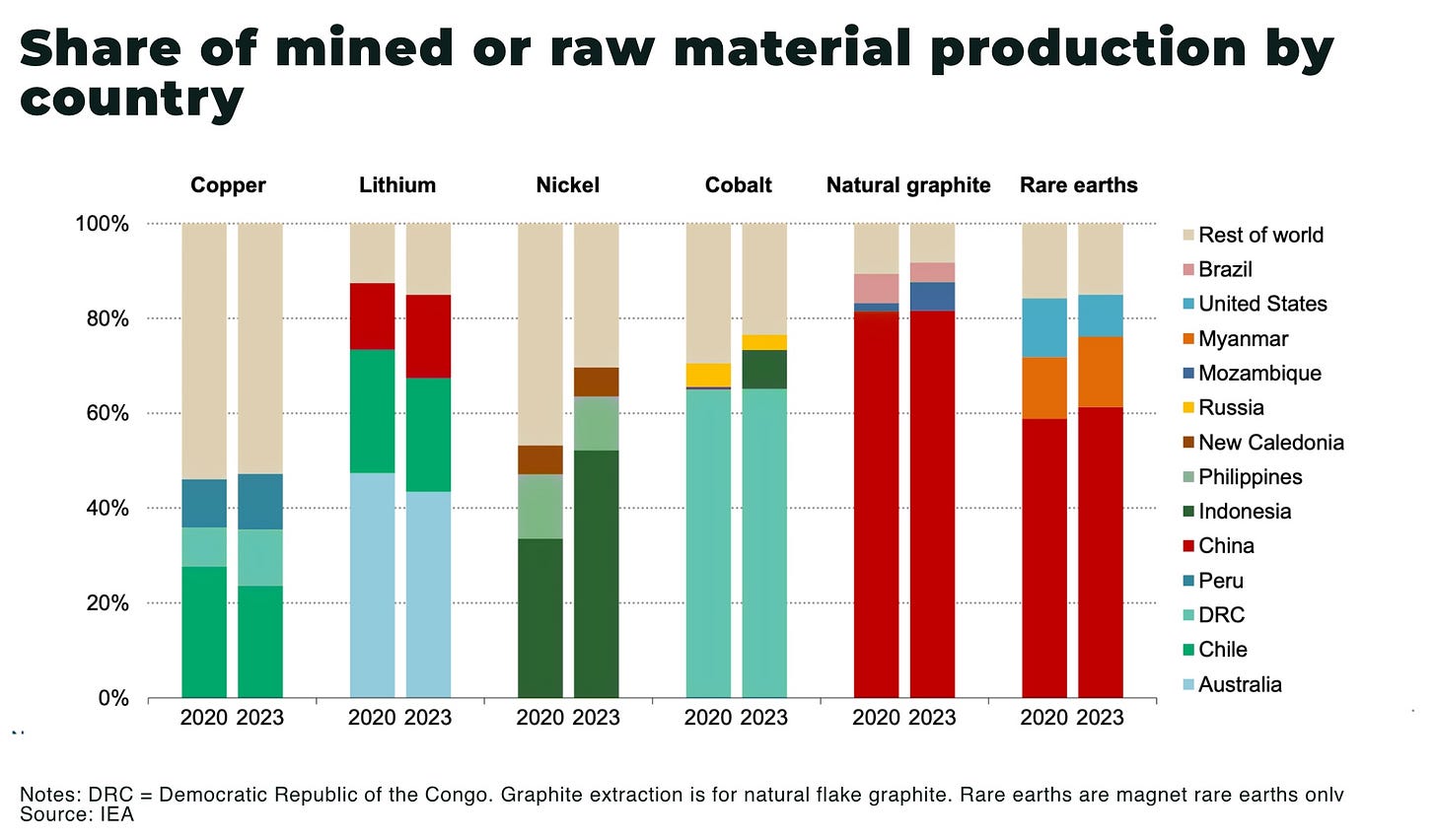

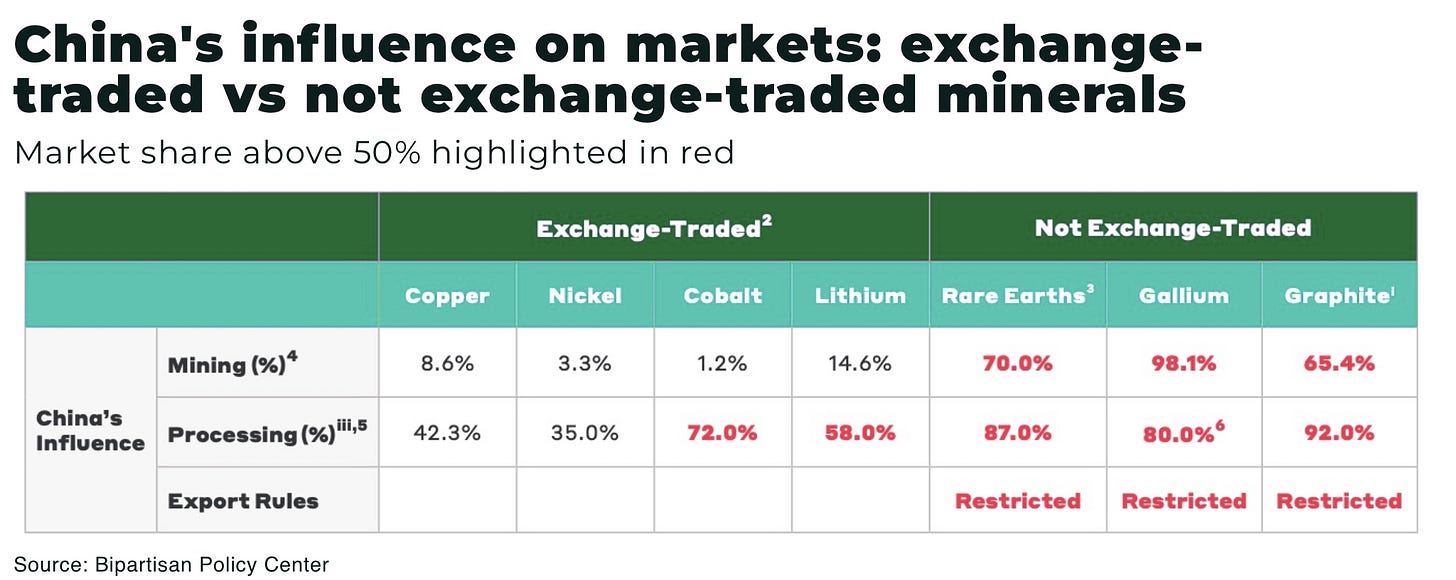

Concern stems from how China dominates global critical mineral supply chains, accounting for 60% of world-wide production.

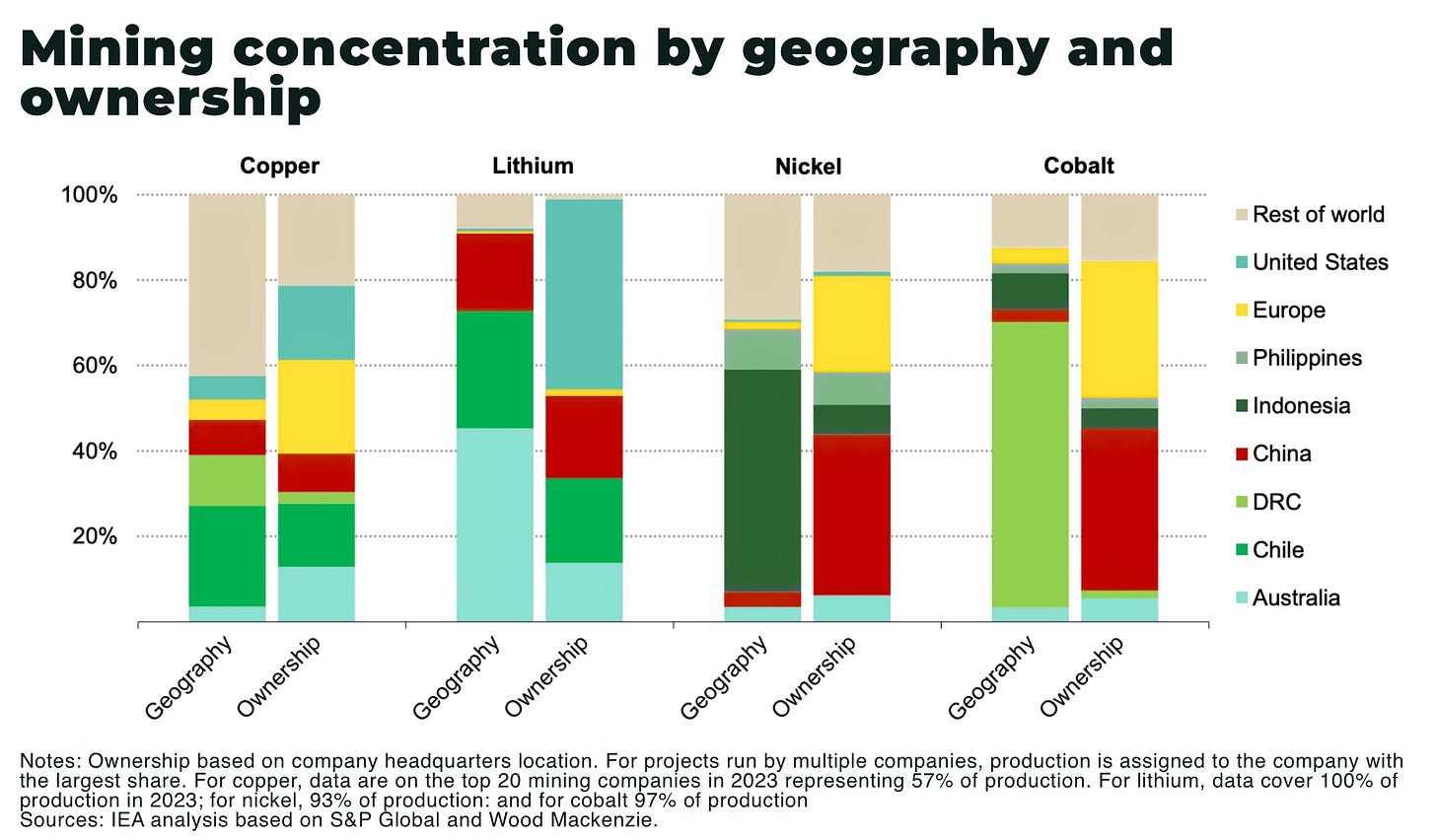

However — and this is the good news — when assessing mining concentration and production by ownership, multi-national mining majors in the US and Europe, such as Rio Tinto and Glencore, play a leading role globally.

vs.

In particular, Western companies play a major role in copper and lithium, while Chinese companies play a bigger role in nickel and cobalt. For example,

- US and European companies produce 20% of global copper supply, Australia and Canada supply 20%

- in Chile, the world’s largest copper producer, European companies are the leading producers with over 10% of production, and US companies controlling the second-largest amount of production

- in Australia and Chile, the largest and second-largest lithium producers in the world respectively, US companies are a major shareholder of over 40% of producing mines

- even in Indonesia, European companies have a share of more than 20% of nickel supply

- and, for cobalt, with the majority of mines located in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), European companies (eg Glencore) and Chinese (eg CMOC) own a third each of the supply

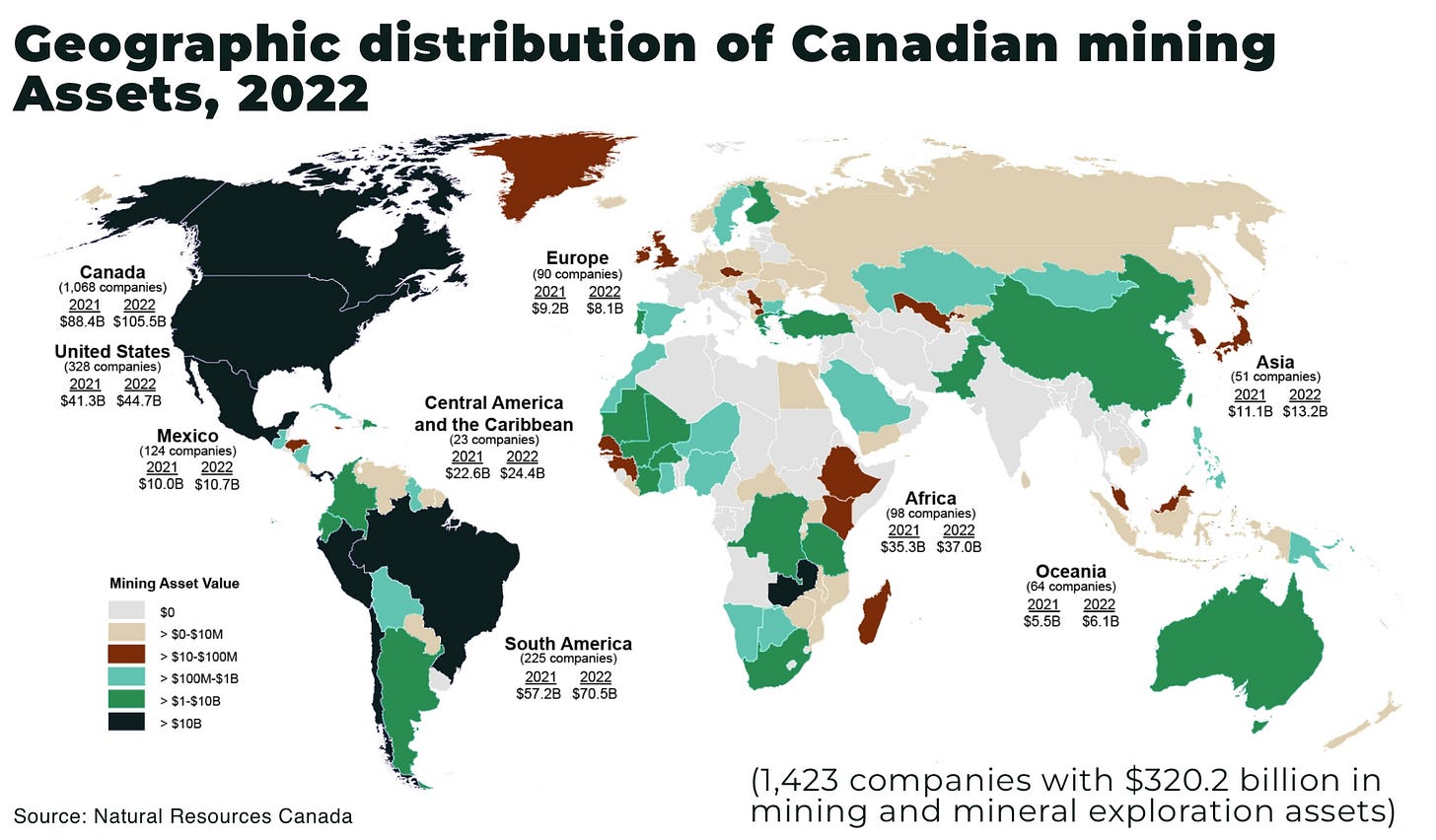

Canada alone is home to almost 50% of the world’s publicly listed mining and mineral exploration companies. In 2022, Canada had 1,423 companies with CA$320.2 billion in mining and mineral exploration assets operating across 98 foreign countries. Mining assets abroad account for about two thirds of the total value of Canada’s mining assets.

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

Many of these jurisdictions across the world lack a free-trade agreement with the US, making them ineligible for tax credits under the US Inflation Reduction Act — but ownership matters, especially as the global trade system is still dominated by both US military might and the US dollar.

China, for example, does not have the overseas military capacity to disrupt these supply chains, unlike the US.

An IMF model suggests that, in a worst-case scenario with global markets splitting into two blocs, based on the 2022 UN vote on Russia’s war in Ukraine — the “US-Europe+ bloc” and the “China-Russia+ bloc”:

- prices for copper, nickel, lithium and cobalt could increase 300% for the China-Russia+ bloc as they lose access to key critical mineral imports (Chile, Congo, etc)

- and the US-Europe+ bloc would see an “oversupply of minerals”

The problem is that the US-Europe bloc would not be able to process this oversupply as it would take “several years” to scale up the refining capacity.

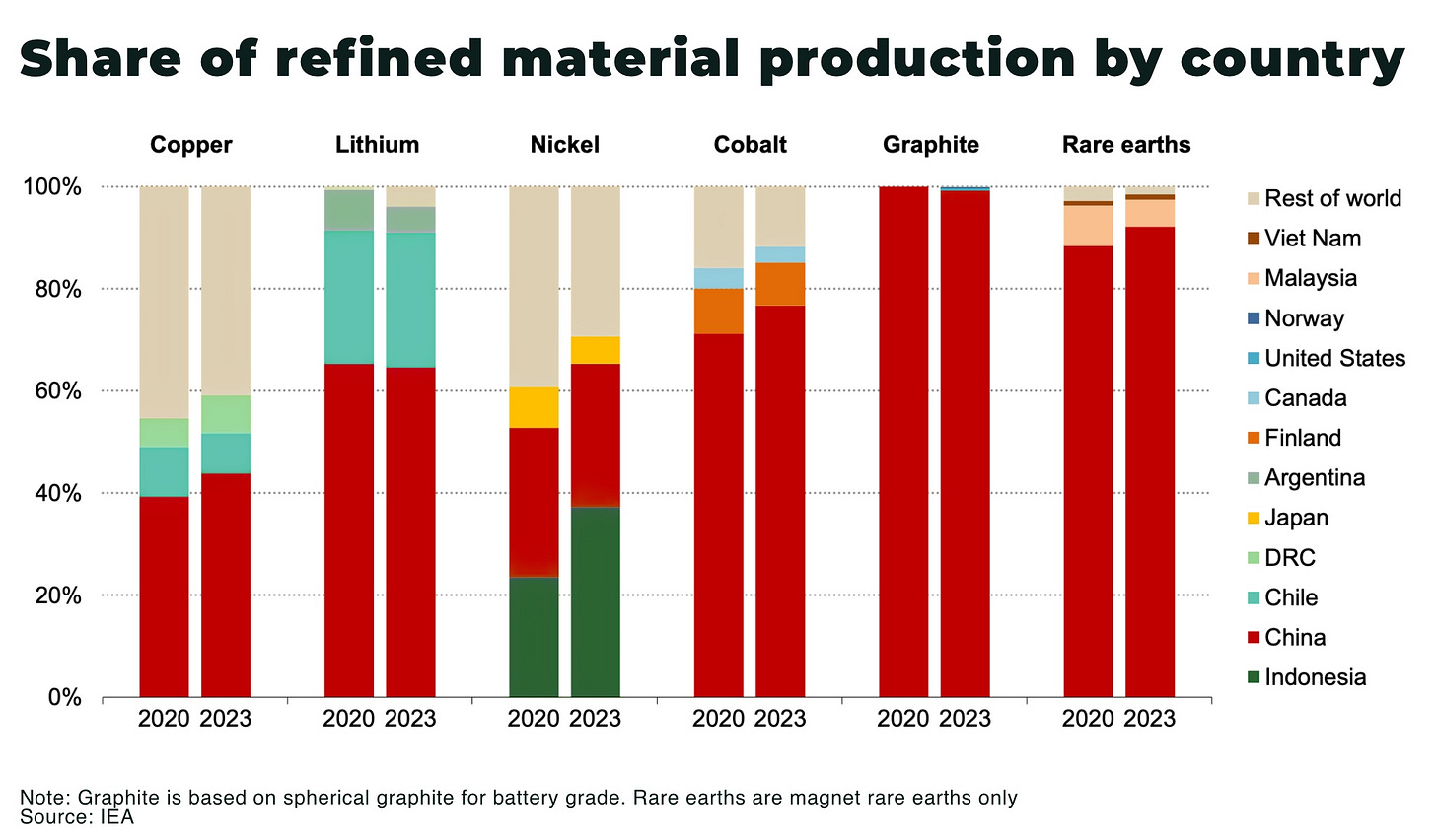

And this is the bad news: the problem is refining.

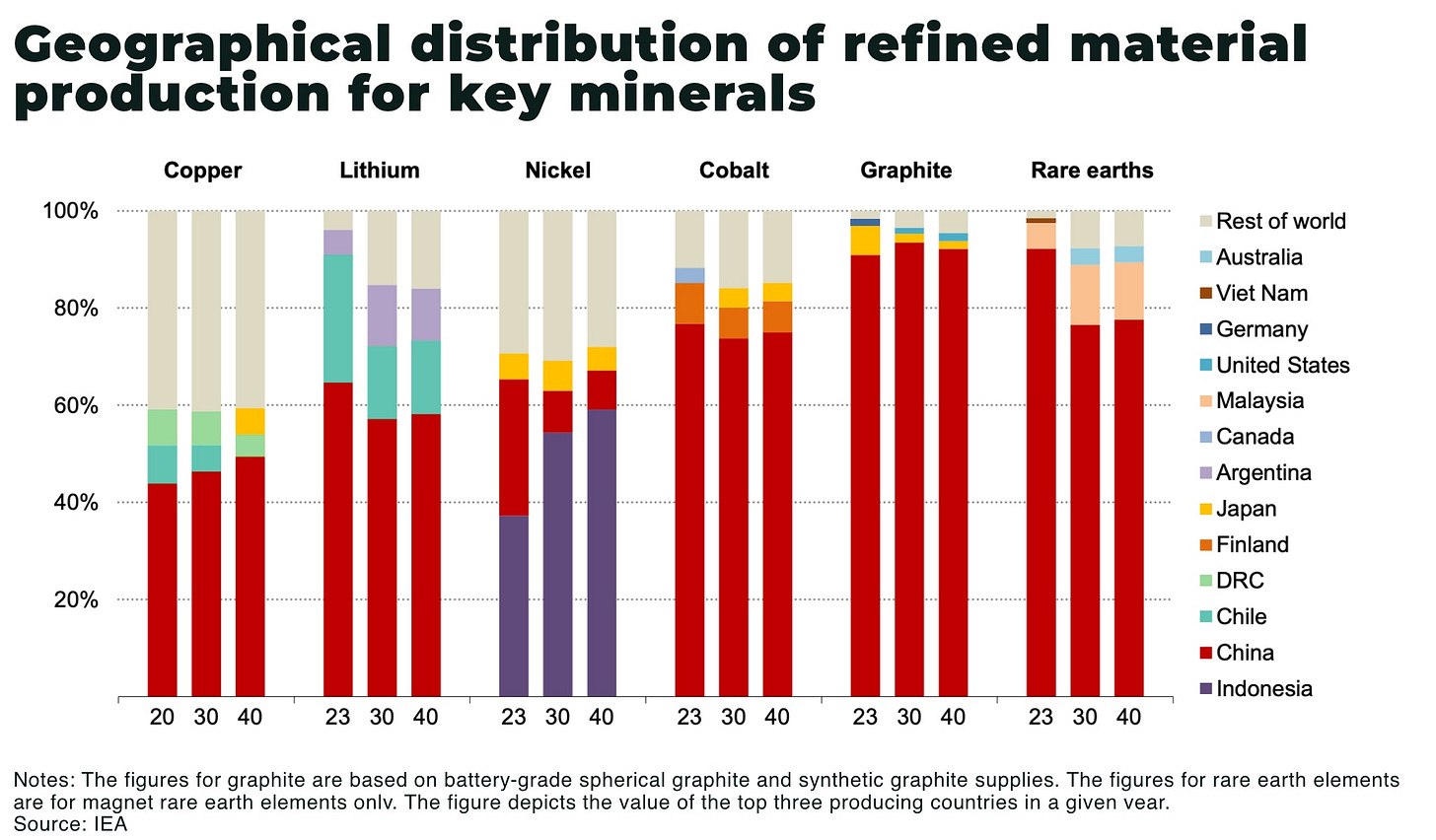

China accounts for approximately 85% of global critical mineral processing capacity. For example,

- China dominates almost the entire graphite anode supply chain end-to-end

- China processes nearly 90% of the world’s rare earths

- over 60% of global processing for lithium and cobalt occurs in China

- over 40% of copper refining is done in China, an increase from under 40% last year, and expected to increase to over 50% from 2030

The US Geological Survey has identified 50 critical minerals, including aluminium, graphite, lithium, magnesium, and nickel — that are essential to everything from electric batteries to advanced medical equipment, electronics to defense systems.

The challenges facing refining outside of China, not just in the West, but also across Latin America and other countries, include:

- cost, with low-margins from smelting, as well as high energy costs

- technical know-how

- environmental concerns; for example, Chile’s Codelco closed its Ventanas smelter after authorities declared an environmental emergency due to pollution that left dozens suffering from symptoms of sulfur dioxide emission poisoning

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

The US is working to fix this dependency on processing from China. For example,

In rare earths,

- Wood Mackenzie’s Rare Earths Market Service estimates demand for rare-earth oxides was 171,300 metric tons in 2022 and projected to increase to 238,700 tons by 2030.

The US Department of Defense has awarded more than US$439 million since 2020 to establish domestic rare earth element supply chains, with a target to create a sustainable, mine-to-magnet supply chain capable of supporting all US defense requirements by 2027

eg MP Materials (the company that restarted the world’s second-largest rare earth mine at Mountain Pass in California), has built a refining rare earth facility on-site and investing US$700 million in the final stage of the supply chain, building a site in Fort Worth, Texas, to produce magnets.

The challenge is that by the end of 2023, only “small amounts” of ore was being refined, with the rest still sent to China

In graphite,

- natural graphite is a critical element for electric vehicle batteries and energy storage systems and is facing a potential 1.2-million-metric-ton supply shortage in 2030, rising to 8 million tons by 2040.

The US Department of Defense entered into a US$37.5 million agreement with Graphite One, under the Defense Production Act, to build out a domestic graphite mining and processing supply chain

In cobalt,

- global demand for cobalt is forecast to double by 2030 — with a deficit in supply of 32%.

In 2023, the US Department of Defense signed a US$15 million agreement with a subsidiary of Jervois Global Limited, to conduct feasibility studies to expand cobalt extraction in Idaho — including studies to assess a domestic US cobalt refinery.

However, investment in mining and refining startups decreased by 12% (to US$375 million) in 2023; for example, lithium extraction and refining attracted US$150 million, below the record in 2021.

China

And, as we noted in our recent analysis — The West’s pursuit of Rare Earths hits resistance from China — China is not standing still in this trade war over critical mineral mining and processing.

Nearly 50% of the market value from refining will be concentrated in China by 2030, according to estimates from the IEA, and then increase further until 2040.

“The lack of diversification going forward, particularly in refining is also a key risk for the security of supply of copper”

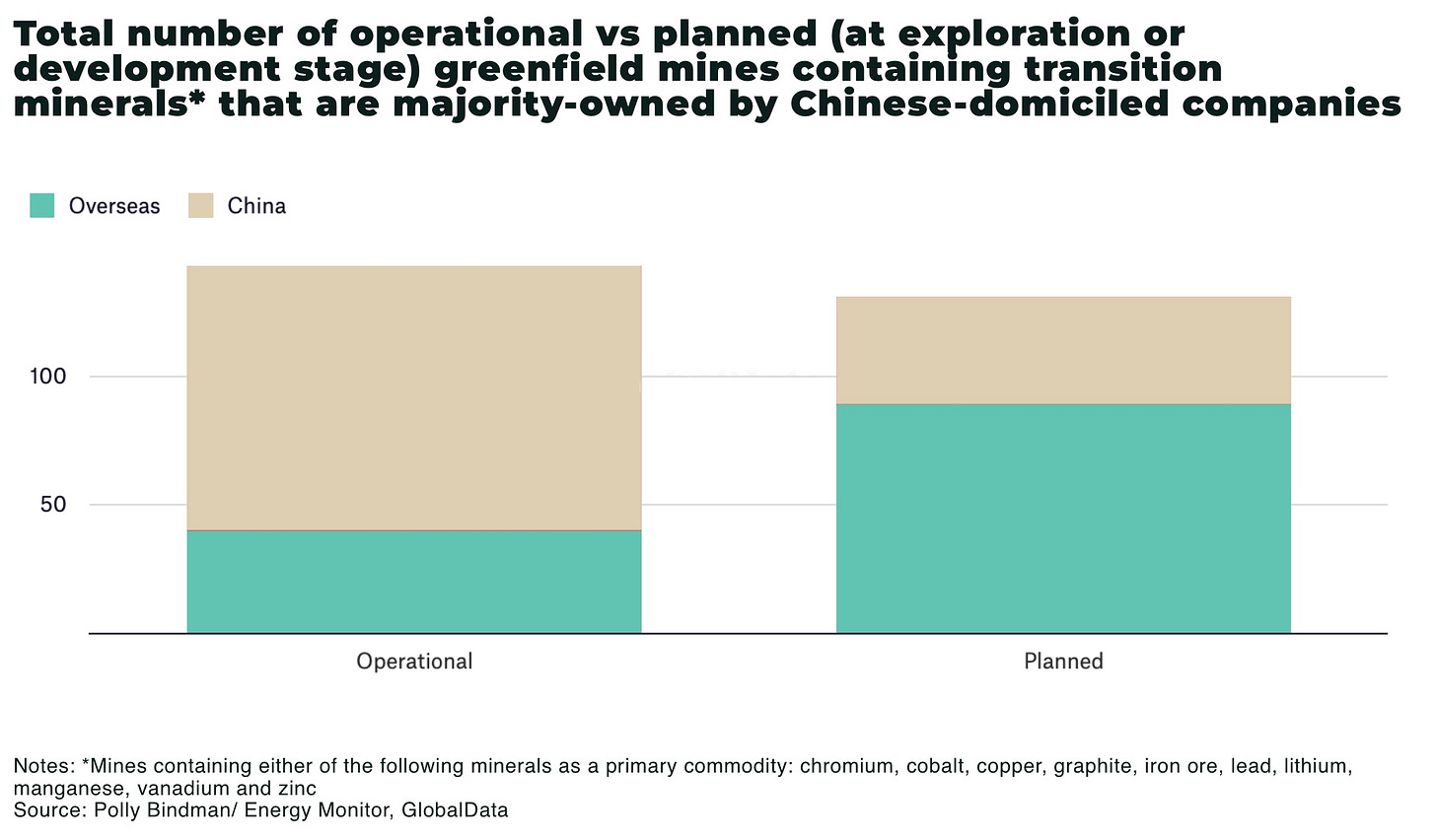

Spending by China on developing and acquisition of overseas mines hit a record US$10 billion in the first half of 2023, focusing on lithium, nickel and cobalt.

According to GlobalData, the number of planned mines owned by Chinese companies, under development or exploration, is set to double.

Refining technology

There are a variety of new technologies being tested in refining and processing of critical minerals that could change the dynamic, especially in the West:

- sensor-based sorting technologies; for example, X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) and Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS): technologies developed to help sort identify and separate valuable minerals from waste in recycling scrap materials more efficiently

- innovative extraction processes; new methods are being developed to extract minerals more efficiently, with less environmental impact, including bioleaching, which uses microorganisms to extract metals from ores, and solvent extraction techniques, that are more selective and less polluting

- advanced refining techniques; for example, hydrometallurgical processes involving aqueous chemistry for the recovery of metals from ores, concentrates, and recycled or residual materials

- electrochemical methods being used in refining to improve the purity and yield of critical minerals, particularly for battery materials like lithium and cobalt

However, as we often warn with new technologies, in the short to medium-term these are largely untested technologies at scale, especially questioning the economic viability of the roll out. We don’t doubt some will be viable by 2040, but not by 2030.

Conclusion

We need more mines, to meet the oncoming expected demand from artificial intelligence data centres and net zero. But that supply will be worthless unless the West builds the capacity of process and refine it — economically, at scale.

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.