- the global nickel market will be in a “substantial 833kt deficit by 2030”

- two major environmental issues are “tailings” and CO₂ emissions

- sustainably sourced nickel offers West opportunity to increase market share

- small-scale investments offer best ways to make efficiencies and scale

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

The Goro mine, at one of the world’s largest deposits of nickel in New Caledonia, has been forced to reduce production to repair a leak in the dam where it stores waste.

The move highlights how, in the nickel industry, environmental concerns are now a priority for investors and consumers.

This matters because demand for nickel is forecast for significant growth. According to Goldman Sachs:

- the nickel market will be in a “substantial 833kt deficit by 2030”

- electric vehicle batteries will generate up to 1.5 million tonnes a year of nickel demand, representing 32% of global nickel demand

One of the biggest challenges for nickel supply to meet this demand are Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues — especially, the issue with waste.

As highlighted by Elon Musk CEO of Tesla, in an earnings call two years ago: “Tesla will give you a giant contract for a long period of time if you mine nickel efficiently and in an environmentally sensitive way.”

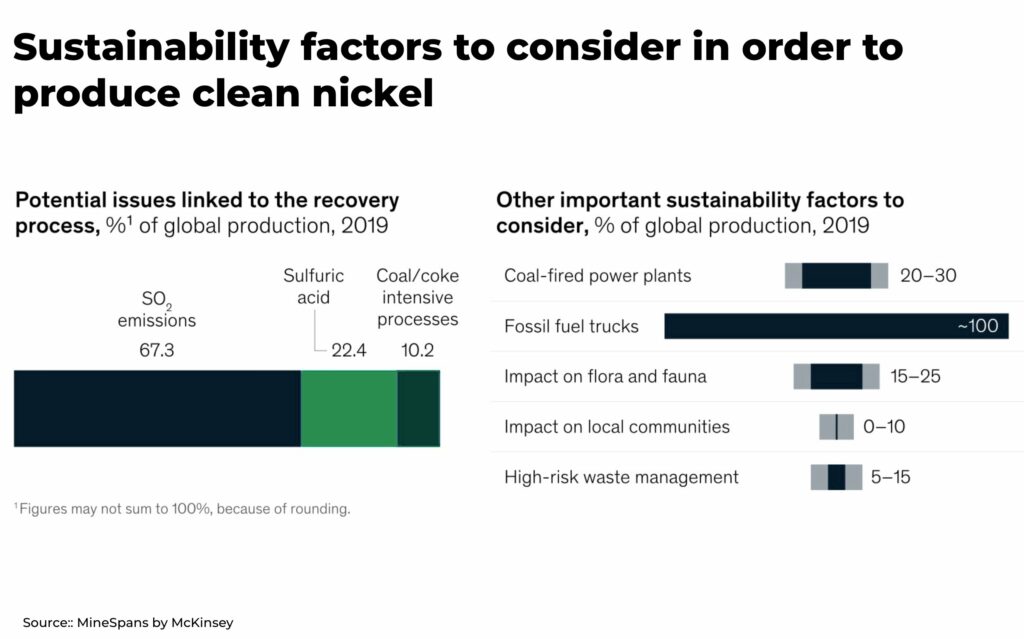

“Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, land use and tailings disposal are the issues most often brought up by stakeholders”

— Dominic Wells, Reseaerch Manager, Wood MacKenzie

The need to mine and process nickel in a sustainable way is also increasing capital expenditure, especially for the West where public and investor demand is higher than for places like China and Russia.

But, in an industry where the West is already struggling to invest and compete, these challenges offer an opportunity to corner the soaring demand for sustainable nickel in electric batteries.

The environmental nickel challenge

The two biggest environmental issues in nickel processing are so-called “tailings” and carbon dioxide emissions.

Nickel Tailings

When ore is mined and processed with High Pressure Acid Leech (HPAL) plants — the dominant processing in Indonesia, Australia and Papua New Guinea — which now accounts for over 47% of global supply — creates a muddy high moisture content waste, called tailings.

Tailings, before any treatment, are highly acidic with typical pH of 1-2, and can contain a multitude of elements such as arsenic, fluorine, sulphuric acid, and other metallic ions.

The first step in disposal is to neutralize the tailings and remove its acidic properties. But then there are still millions of tonnes of neutralized tailings to dispose of safely. Some of the main ways include:

Ramu mine, in Papua New Guinea, neutralizes its tailings and disposes of them via a deep water canyon, about 3km deep, and onto the ocean floor. The Ramu river deposits approximately 80 million tonnes of solids every year onto Basumuk Bay’s surface, and the mine adds an additional 5 million tonnes to the deep water canyon, but well below surface and well below the sunlight zone where marine life survives. Environmental groups have fought this type of Deep-Sea Ocean Tailings Disposal, claiming it impacts both local communities and the ocean coral, neither of which claims have been proven accurate.

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

For land storage tailings: Ambatovy mine, in Madagascar, uses a process copied across Indonesia, Cuba, the Philippines and New Caledonia. The tailings are (partially or completely) neutralized and dewatered (to the best extent possible), and stored on land. Goro is undergoing a change to this method by trying to reduce the volume of solids by removing almost all of the water from the tailings before storing on land, in an effort to increase tailings storage capacity (tailings can be over 60% moisture so the water takes up a lot of on land space, even after “dewatering”.). The problem is that, not only is removing the water from millions of tonnes of slurry a year is expensive, but once it’s done and stored on land, many of these regions have high net rainfall turning it back into a slurry in what are often seismic zones. And these on-land tailings dams do fail and can have significant human and environmental consequences when they do, as we’ve unfortunately seen in Brazil and Canada in recent years.

Mines in Australia, such as Murrin Murrin and Ravensthorpe, are located in the desert and so the water quickly evaporates, leaving little but dry residue that will not leak into the ground water

Chinese companies often operate to the ESG standards set by the Chinese government and the country they operate in. But Western companies are increasingly sensitive to consumers and nickel from Australia to Finland, Japan to the US who want their nickel sourced sustainably.

According to one estimate, 40% of global nickel reserves are in locations with high biodiversity and protected areas, and 35% in areas with high water stress.

Carbon Dioxide emissions

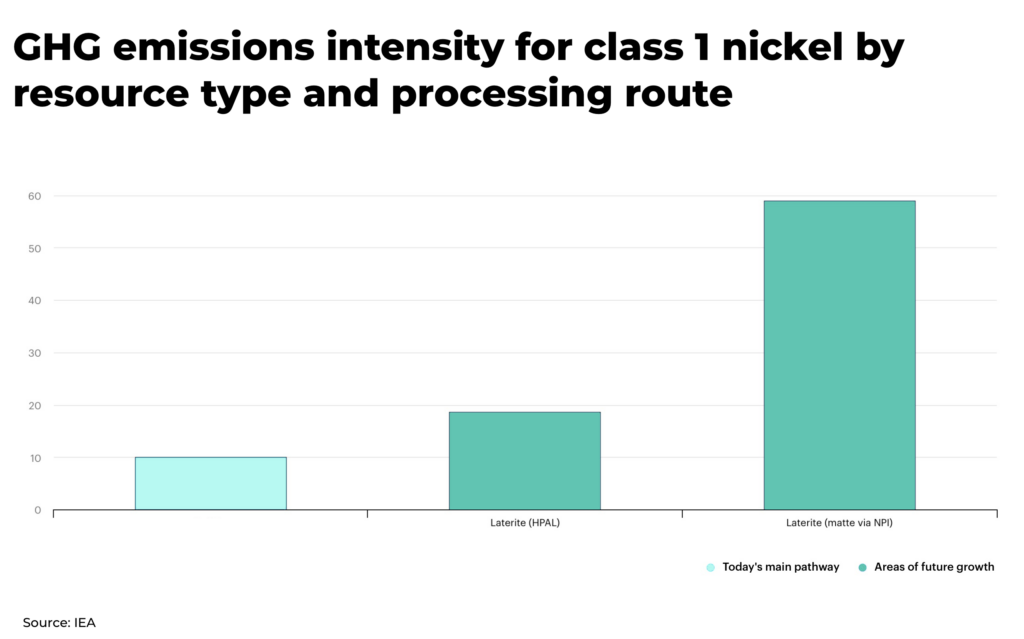

One way nickel processing plants are trying to overcome the problem of toxic tailings, is to shift away from HPAL plants and use their Nickel Pig Iron (NPI) furnaces to create nickel matte.

This process creates tailings that are a solid, glassy waste. It’s already being used in PT Vale and Tsingshan’s Morowalli park, both in Indonesia. The process doesn’t need to be neutralized and can be stored in any weather without significant impact on the environment.

The problem is that Nickel Pig Iron is one of the most energy intensive ways to produce nickel.

Average carbon intensity for the nickel industry is approximately 30 tonnes of carbon per 1 tonne of nickel (Skaarn and Wood Mackenzie analysis). But this rises to nearly 60-80 tonnes of carbon for NPI, and to then further process NPI into a matte typically requires another 10 tonnes of carbon per tonne of Ni.

The environmental challenges are significant, but also offer an opportunity for investors.

A diversity of nickel opportunities

We expect deep-sea tailings will continue to be used by HPAL plants in places such as Ramu in Papua New Guinea, while regions with high rainfall and seismic risks will begin to shift to NPI processing.

Which leaves huge demand to supply the Western market with sustainably sourced nickel.

For example, the environmental issues were a major reason why Tesla avoided purchasing nickel from Indonesia, and instead invested in the Goro mine in New Caledonia. But as we’ve seen, they also experiencing problems.

The way forward, as highlighted in our previous nickel analysis on how to encourage investment, is to start small.

With smaller processing facilities, it’s possible to introduce and refine sustainable practices such as recycling liquid tailings or sequestering carbon emissions. And, once these efficiencies are proven, it’s possible to scale bigger quickly.

One example is junior mining company Brazilian Nickel, a UK company, using a pioneering process called Heap Leaching for nickel laterites, which is less capital and energy intensive than HPAL processing, and so better for the environment. However, this process appears unique to the ore as historical attempts at heap leaching laterites (Murrin Murrin and Caldag in Turkey) have not been successful.

Brazilian Nickel have started with a small-scale plant in Piauí , northeast Brazil, producing approximately 1,500 tonnes a year. This will allow them to prove the technology and improve the efficiencies.

“Producing nickel in NHP [nickel hydroxide product] from our low-carbon process will help the planet’s race to combat climate change. The product will feed the ever growing demand from electric vehicles”

— Mike Oxley, Chief Executive Officer of Brazilian Nickel

And, unlike so many other larger scale investments, they are now operational.

Start small with your investment, but get ready to scale big.

Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.