Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

An inside look into what’s gone wrong in Washington — and how to fix it

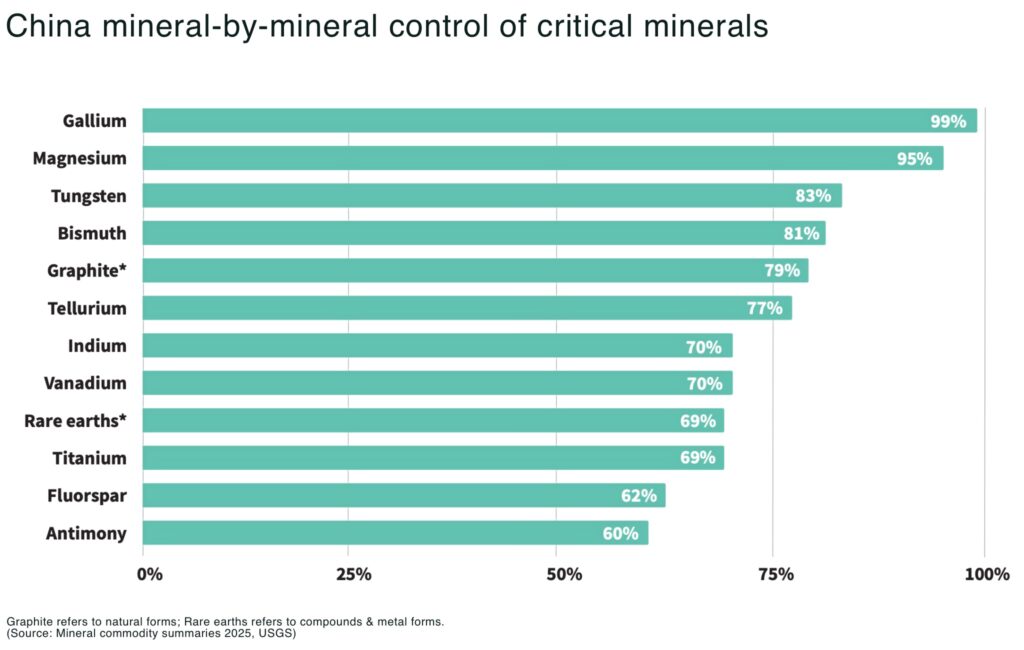

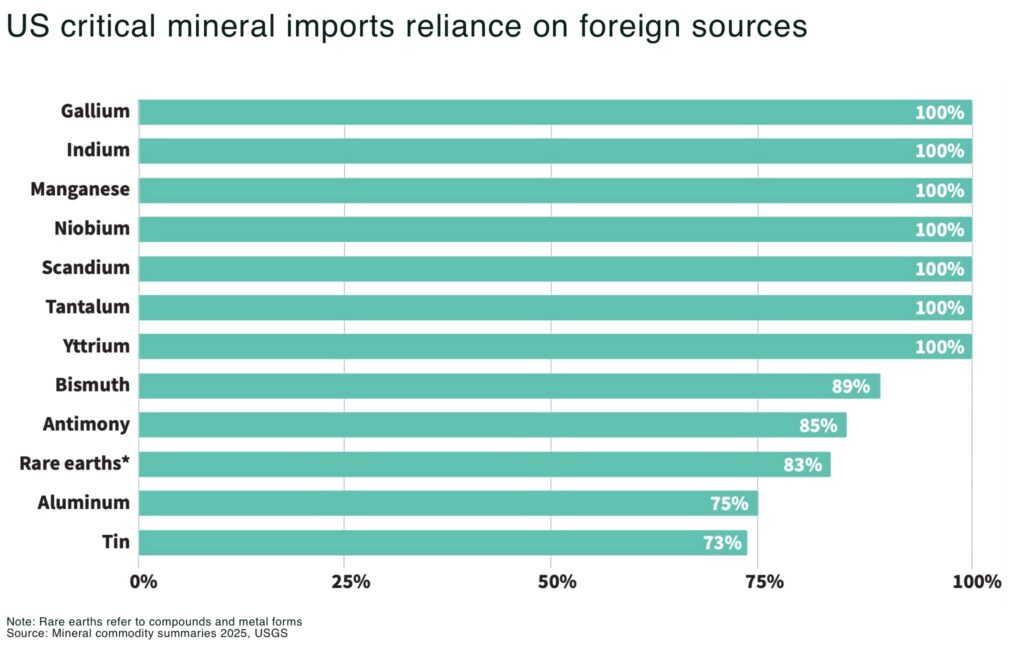

In December 2024, China banned exports of gallium, germanium, and antimony to the US, before adding 7 more minerals, from tungsten to rare earths, just months later. The move exposed a structural weakness in the Western alliance: America depends on China for more than 90% of processing capacity for key critical minerals.

Why did the US fail to secure critical mineral supply chains?

‘What emerged from our interviews is that the true vulnerability lies in the rest of the economy. The next evolution of U.S. policy must abandon the assumption that defense alone can carry the burden of industrial transformation” — Critical Minerals and the Business of National Security, Stanford Gordion Knot Center for National Security Innovation

This article draws extensively on research from the Stanford Gordian Knot Center for National Security Innovation. The report, Critical Minerals and the Business of National Security (September 2025), is based on more than 60 interviews with current and former US officials across the Departments of Defense, Interior, Commerce, and Energy; Congressional offices; intelligence community; allied governments; national laboratories; critical mineral suppliers and processors; institutional investors; and supply chain teams within major defense, automotive, and technology firms.

It gives an insight — and corroborates our own conversations and research — into how fragmented federal policy, misaligned private-sector incentives, and China’s decades-long industrial strategy have left the US dependent on foreign processing for critical minerals.

Critical minerals are a foundation for modern defense and technology — used to build everything from missile casings and fighter jets to semiconductors and EV batteries. The technology is available, but without access to essential minerals, production is impossible.

The (draft) US Geological Survey lists more than 54 minerals as “critical” due to supply risks and national security importance. Yet, despite significant domestic deposits and allied resources, the US has outsourced key mining and processing supply chains to China.

The US has the second longest mine development times in the world, at almost 29 years on average from first discovery to first production, according to a report by S&P Global. Only mines in Zambia take longer, at 34 years.

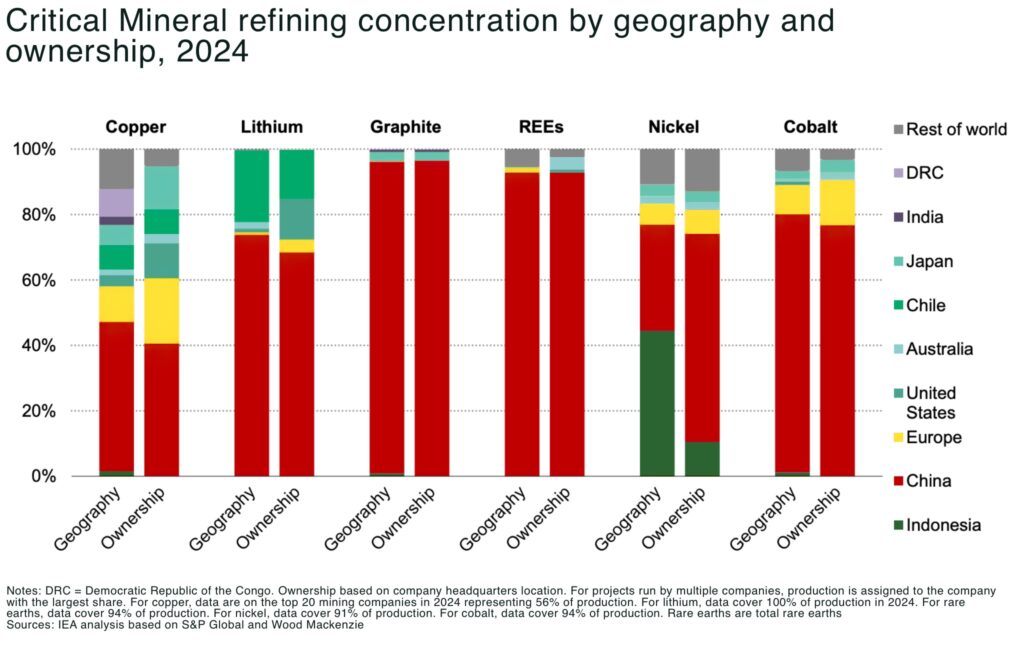

But, even if mines were built faster, almost all the ore would still be shipped to China for refining — as we have previously highlighted, processing is the real chokepoint.

How did this happen?

There is both push and pull: push from the West for environmental and cost motives, and pull into China to develop its economy and gain long-term control over the supply chain.

An important part of the story is acknowledging the role Western nations played in creating this vulnerability. For decades, free-market policies, globalization trends, and environmental constraints pushed capital away from US projects — and supporting China’s push to capture the sector.

For decades, the West has been eager to outsource mineral processing, an environmentally hazardous and toxic process — expensive if you need to meet all the environmentally-friendly criteria. China was willing to bear these costs.

However, China’s dominance was not accidental. Since the 1980s, Beijing poured billions into vertically integrated mining and processing, subsidizing output, driving Western rivals into bankruptcy, and later acquiring their assets. For example, in 2023 alone, China invested US$16 billion in mining capacity abroad.

China accounts for approximately 85% of global critical mineral processing capacity. For example,

- China dominates almost the entire graphite anode supply chain end-to-end

- China processes nearly 90% of the world’s rare earths

- over 60% of global processing for lithium and cobalt occurs in China

- over 40% of copper refining is done in China, an increase from under 40% in 2023, and expected to increase to over 50% from 2030

In short, to sustain its advantage in the critical minerals sector, Beijing executed a systematic strategy to eliminate Western competition:

- overbuilding processing capacity far beyond domestic demand to flood global markets

- collapsing prices through state subsidies to drive Western firms into bankruptcy

- acquiring distressed Western assets and intellectual property to consolidate control over global supply chains and entrench its monopoly

As one former National Security Council member put it anonymously to the Standford researchers: “Beijing sought to become the Saudi Arabia of critical minerals. They succeeded.”

“China’s dominance of the critical mineral supply chain did not happen by accident. Decades and billions of dollars were employed to create this asymmetric dominance by the CCP” — said one former National Security Council member.

The Stanford report highlights this practice with a case study of Ingal Stade, Europe’s sole producer of gallium, that was driven into bankcruptcy in 2016 when it faced competition from heavily subsidized Chinese companies that undercut prices, eventually forcing it into bankruptcy. This example underscores the core challenge: “The collapse of Ingal Stade removed a key non-Chinese supplier, leading the U.S. to be 99% reliant on the remaining, Chinese-owned sources for gallium. Once rival companies were out of business, China raised prices again, cementing its asymmetric control over a critical-minerals bottleneck” — Critical Minerals and the Business of National Security, report

The ICMM’s new Global Mining Dataset highlights the fallout of America’s critical mineral policies. Of the 15,188 mining and processing facilities globally, nearly half are concentrated in just three countries: China, the US, and Australia . But China leads by far in metallurgical facilities, with 426 — over three times the US count (120).

The key question for successive administrations in Washington: why has this happened despite so many red flags raised — both inside and outside government — before China implemented the restrictions. And can the US redeem the situation?

A fragmented US response

The Stanford study found the US government response to be incoherent, describing the landscape as a bureaucratic “Spaghetti Monster” of more than 40 agencies with overlapping or conflicting mandates.

Critically: of the 62 critical minerals designated by at least one federal agency, only four appear across all lists .

This fragmentation undermines strategy, investment, and planning. As one Interior Department official said: “We need a shared map and a shared playbook. Right now, each agency is optimizing its own corner.”

“The DoD’s list is wrong. The focus should be on specific materials and their processing, not just the raw elements. Even further, Energy shouldn’t be concerned with manganese sourced from Gabon and South Africa. What matters is manganese oxide used for batteries. Therefore, manganese itself shouldn’t be listed as critical, only manganese oxide should be” — a current Department of Energy official

Private sector misalignment

Even when government demand action, private capital hesitates. Investors see long permitting timelines, high costs, and the risk of China manipulating prices.

“Private capital does not want to touch it. Permitting takes too long. Costs more. And the track record is poor,” one institutional investor told researchers.

Defense contractors face similar misaligned incentives. The Department of Defense accounts for less than 5% of global demand for critical minerals, so while defense requirements are often used to justify supply chain reshoring: the Pentagon is too small to move markets. So, often, contractors are pushed to minimize costs, even if it means sourcing from Chinese suppliers.

“DoD contractors are not willing to pay a premium for friendly sourcing,” a former defense official said.

As a result, defense primes are currently sourcing from opaque global supply chains that rely on Chinese-controlled refining and midstream processing. These dependencies are widespread throughout the defense acquisitions industry, resulting in the US supporting the very competition from which it is trying to decouple.

While Congress has attempted to steer procurement behavior— such as through Section 857 of the FY23 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) — the report suggests that these efforts are set up to fail: enforcement is limited, waivers are common, and actual sourcing behavior is unlikely to change. Defense contractors will often still continue to prioritize cost and timeline adherence, even when it means sourcing materials from adversary-controlled supply chains.

In one illustrative case highlighted in the report, a major US defense prime conducted a rare deep trace of its titanium supply chain — reaching 13 tiers down. It led directly to “Chinese mines, Chinese roads, and Chinese trucks” as confirmed by their supply chain specialists. When the firm disclosed this to the DoD, the firm was penalized for delays caused by the trace itself. Since then, the firm has deliberately reduced its supply chain diligence, thereby avoiding future liability and constraints; despite knowing that Chinese-sourced materials continue to flow into their systems.

Western companies, driven by short-term shareholder returns, simply cannot compete with state-backed actors operating without market constraints.

How to fix it

The major conclusion from the report suggests: relying on the free markets to self-correct is no longer an option.

The Stanford report outlines three main solutions:

- regulatory realignment: establish a single national strategy and align procurement mandates with long-term resilience. Expand authorities under the Defense Production Act, and reform the tax code to support investment

- market protection and demand guarantees: use tariffs, stockpiling, and long-term offtake agreements to shield US firms from China’s price manipulation. Guarantee demand through procurement, even at a premium, to de-risk private investment

- allied coordination: work through frameworks like the Minerals Security Partnership and AUKUS to align policies, pool capital, and create collective resilience. Tariffs on allied producers under Section 232 should be revised to strengthen trust and co-investment

And we can now see this policy trend playing out, from Department of Defence’s investment in MP Materials for rare earth mining and processing, to the Trump administration’s o to increase domestic mineral production.

Why it matters

Across nearly every interview in the poret, it was clear that cost, not resilience, determines sourcing behaviors within the private sector. Private firms prioritize low-cost inputs to preserve margins — and will continue to source from China, even when doing so increases national vulnerability.

Market forces alone will not resolve the national security crisis. The US faces a classic market failure: China’s industrial strategy has depressed prices to the point where private capital cannot compete and resilience will not emerge on its own. To reverse this trajectory, the USmust pursue dramatic regulatory, organizational, and industrial policy to safeguard the nation’s long-term national and economic security.

As we have warned, America’s current critical mineral strategy threatens disaster.

This is not a market quirk — it is a national security crisis. As the Stanford report concludes: “Time is not on the United States’ side. The US can choose to act now, decisively, and together with partners and allies, or risk being forced to react under circumstances beyond its control.”

As the impact of export restrictions across automakers, aerospace industry, defence and across industry has highlighted — the West has, at the moment, almost no where else to turn.

For investors, the implications are clear: expect policy to shift further toward subsidies, tariffs, and government-backed offtake agreements. Strategic mineral developers positioned in the US or allied jurisdictions stand to benefit, provided they can survive long permitting timelines and regulatory uncertainty.

The US has the resources and capital. What it lacks is coordination. Unless Washington can realign its strategy, it risks fighting tomorrow’s wars with supply chains controlled by its adversaries.