- China suspends export ban on three critical minerals — gallium, germanium and antimony

- Beijing frames controls as national-security licensing, not a permanent ban, signalling strategic flexibility rather than supply-chain guarantee

China has suspended the export ban on gallium, germanium and antimony to US until November 27, 2026. Exports will now be managed under licensing until 27 November 2026, but the clause banning exports to military end-users remains in effect.

The move comes after a wider trade truce between China and the US after a meeting between US President Donald Trump and President Xi on November 1.

Chinese state-media commentary emphasises that export controls are normal regulatory practice for dual-use items and the re-opening is aligned with international norms.

In December 2024, China’s Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China (MOFCOM) announced that “in principle” exports of gallium, germanium, antimony and super-hard materials to the US would not be permitted. The ban was a direct retaliation to US semiconductor export restrictions and a signal of Beijing’s willingness to use critical‐mineral control as leverage.

China dominates the production and processing the gallium, germanium and antimony:

- total global antimony mine production in 2023 was approximately 83,000 tonnes. The largest producer, by far, is China

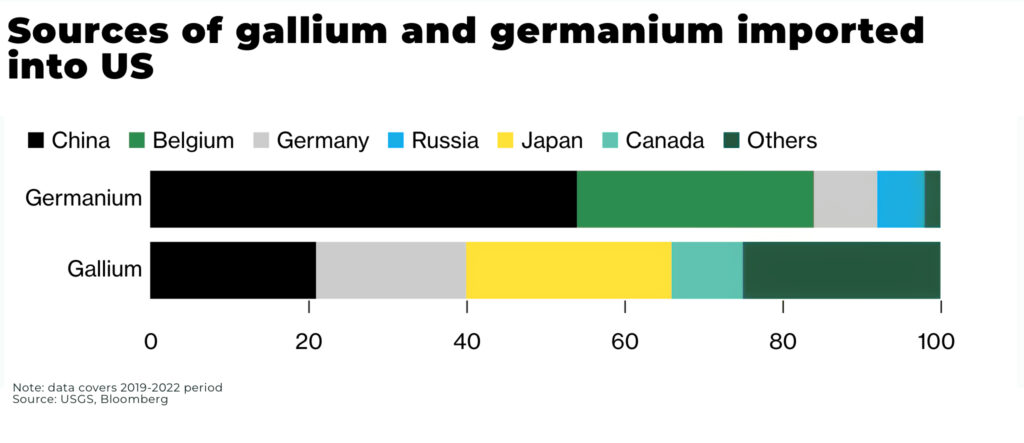

- and, China enjoys a near monopoly on global supply of both gallium and germanium: gallium: 94%, germanium: 83%

Why it matters for critical-minerals supply chains

A report, released in November, by the US Geological Survey, warned there could be a US$3.4 to 9 billion decrease in US GDP if China implements a total ban on exports of gallium and germanium, minerals used in some semiconductors and other high-tech manufacturing:

- gallium is used in high-frequency semiconductors, 5G, LEDs and photovoltaics

- germanium is critical for fibre optics, infrared sensors and advanced chips

- antimony is deployed in flame retardants, batteries, aerospace, and defence alloys

While the ban is suspended, export licensing remains, and the military‐end-use ban stays active. That means Beijing retains the ability to re-activate stricter controls. Chinese media explicitly say export controls are lawful regulatory tools, not ad-hoc trade weapons.

What remains unresolved and what to watch

- licensing volumes and destinations: How many shipments are approved under the new regime, and to which end-users? Transparent data is limited

- duration and durability: the suspension runs until 27 Nov 2026, after which Beijing can flip the switch again. Markets should price for optionality, not certainty

- broader export-control architecture: China’s rare-earth export mechanism (eg, heavy rare earths, downstream alloys) remains only partly eased; full liberalisation has not occurred

- sSmuggling/enforcement risk: as noted by Chinese authorities, trans-shipment and third-country routing are expanding — enforcement and licensing transparency will matter

This decision marks a tactical thaw in one of the most acute chokepoints of global critical-minerals supply chains. However, the strategic dependency remains: China still retains the upstream leverage.

In conclusion: the ban’s suspension is meaningful — but it isn’t a guarantee of open supply. The upstream remains tilted toward China; investors and policymakers should view the move as a reprieve, not a resolution.