Subscribe for Investment Insights. Stay Ahead.

Investment market and industry insights delivered to you in real-time.

- US has backed a $7.4bn critical minerals smelter to be built by Korea Zinc, the world’s largest zinc smelter

- facility, planned for Tennessee, will process antimony, gallium, germanium, zinc, copper, lead, precious metals, and rare earths

- commercial production expected to ramp between 2027 and 2029

The US has thrown its weight behind a US$7.4bn critical minerals processing plant to be built by Korea Zinc, underscoring how refining and smelting — not just mining — have become a key strategic battleground in the global minerals race.

Korea Zinc confirmed that the US government requested the facility to address mounting supply-chain risks for metals essential to industries ranging from automotive and electronics to defence systems. The move comes as Washington steps up efforts to counter China’s dominance across downstream processing, where Beijing controls large shares of global refining capacity for multiple strategic metals.

This is not a marginal project. It is one of the largest foreign investments in US critical minerals infrastructure to date—and a clear signal that the US is now willing to deploy capital, policy tools, and allies to rebuild industrial capacity it allowed to atrophy for decades.

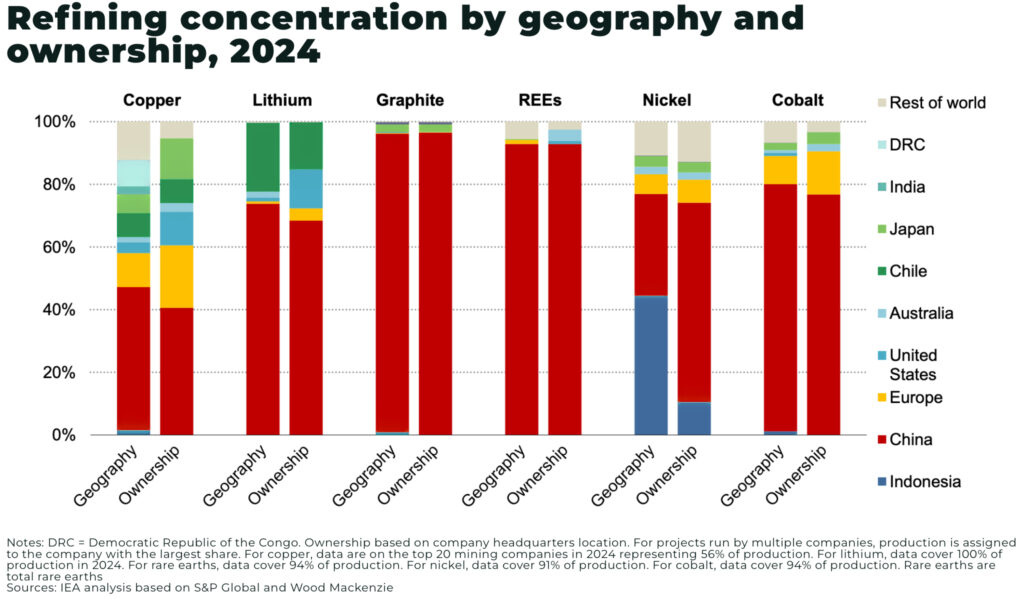

Crucially: China accounts for approximately 85% of global critical mineral processing capacity.

What will the smelter produce — and why it matters

According to regulatory filings and disclosures, the Tennessee facility will produce a wide slate of materials, including antimony, gallium, and germanium, alongside zinc, copper, lead, precious metals such as gold and silver, and rare earth elements.

As have highlighted in our analysis, these are not niche metals:

- antimony is critical for flame retardants, ammunition, and military alloys

- gallium and germanium are essential inputs for semiconductors, power electronics, radar systems, and infrared optics

- zinc and copper underpin everything from grid infrastructure to EV charging networks

China currently dominates the processing of many of these materials and has placed strict export controls on several, including germanium and gallium, over the past two years. That reality has forced US policymakers to confront an uncomfortable truth: domestic mining means little without secure downstream capacity.

Project structure: public capital, private execution

Korea Zinc’s board has approved the formation of a foreign joint venture that will include the US government, an unusually direct level of state involvement for a metals processing project.

The JV is expected to raise around $2bn, with the remainder of funding coming from a mix of US government loans, grants, and capital contributions from Korea Zinc. The company plans to acquire and redevelop a Nyrstar-owned smelting site in Tennessee, upgrading it to produce 13 different metals and sulphuric acid used in chipmaking.

Target output levels are substantial:

- 300,000 tonnes of zinc per year

- 35,000 tonnes of copper

- 200,000 tonnes of lead

- 5,100 tonnes of rare earths annually

Commercial operations are expected to begin gradually between 2027 and 2029, placing the project squarely within the window when analysts expect structural deficits in multiple critical minerals to intensify.

Why Korea Zinc — and why now?

Korea Zinc is the world’s largest zinc smelter and a producer of several materials already under Chinese export controls, including antimony, indium, tellurium, cadmium, and germanium.

The project also follows a broader South Korea–US economic realignment. In late October, Seoul agreed to invest US$350bn in the US as part of a trade deal aimed at reducing tariffs and strengthening strategic supply chains. Korea Zinc’s chair was part of a senior South Korean business delegation to Washington earlier this year, highlighting the political weight behind the investment.

Markets reacted quickly. Korea Zinc shares jumped as much as 27% following local media reports of the agreement, reflecting investor recognition that state-aligned processing assets now command strategic premiums.

The Bigger Picture: From Mining Security to Industrial Sovereignty

This project reinforces a critical shift in US policy thinking. The focus is no longer just on securing upstream supply, but on rebuilding industrial sovereignty across the entire value chain.

Smelters are expensive, politically sensitive, environmentally complex, and slow to permit — precisely why China dominates them. By underwriting a $7.4bn facility with an allied operator, the US is signalling that processing capacity is now a national-security asset, not just an industrial one.

Find out more from our analysis on how refining is the chokepoint:

(Photo credit: Korea Zinc)